Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

H.P. Lovecraft is a polarizing figure nowadays—even if you ignore all the hugely problematic elements of his writing. But he still pioneered so much of what we love in horror and science fiction. So award-winning author Victor LaValle decided to create a literary tribute to the Master.

LaValle has written a brand new novella called “The Ballad of Black Tom,” which just became the first title to be acquired for Tor.com’s new novella line by editor Ellen Datlow.

http://www.amazon.com/Ballad-Black-T...

LaValle explains the genesis of this tale thusly:

The Ballad of Black Tom was written, in part, during the latest round of arguments about H.P. Lovecraft’s legacy as both a great writer and a prejudiced man. I grew up worshipping the guy so this issue felt quite personal to me. I wanted to write a story set in the Lovecraftian universe that didn’t gloss over the uglier implications of his worldview. I also wanted it to be a hell of a lot of cosmic doom-filled fun.

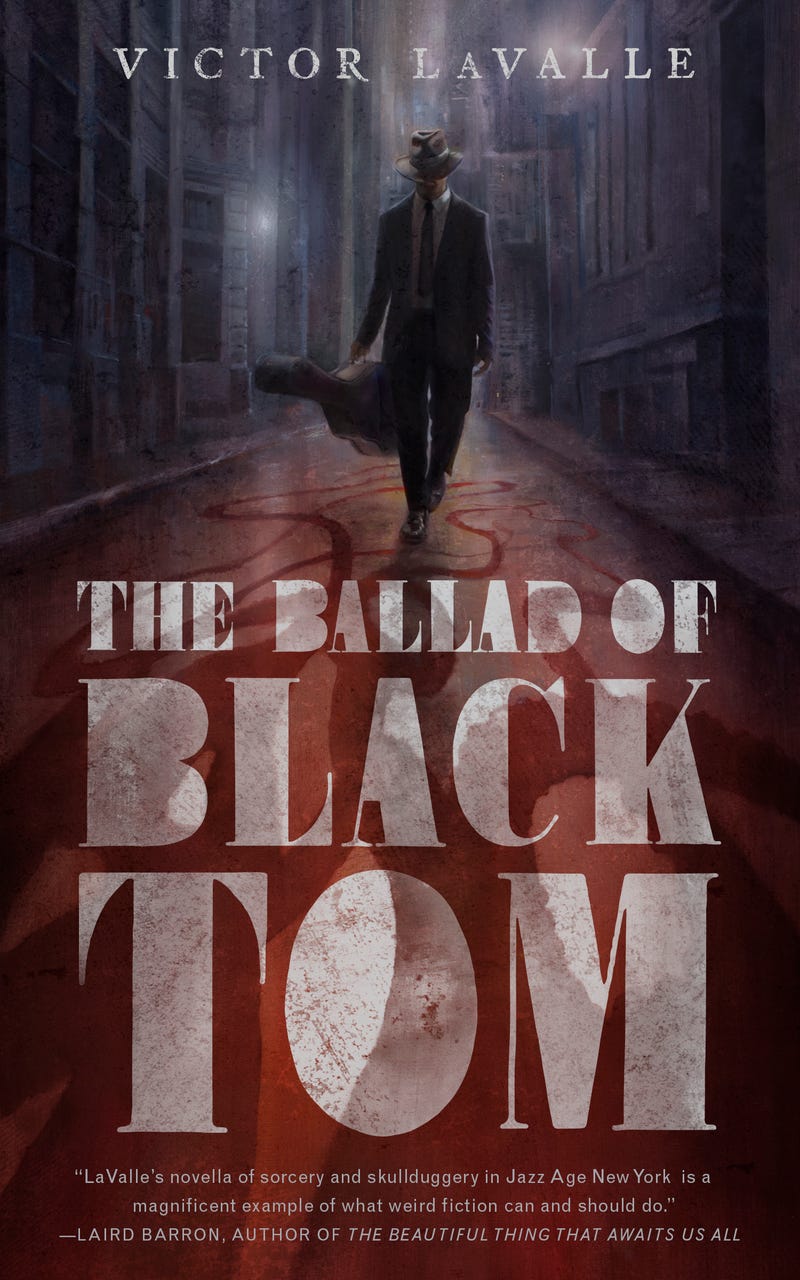

We’re thrilled to be able to bring you the cover art to this novella, exclusively at io9, featuring art by Robert Hunt design by Jamie Stafford-Hill. Here it is in all its glory (and scroll down for an exclusive excerpt, too):

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

In “The Ballad of Black Tom,” Charles Tom Tester hustles to keep food on the table and a roof over his father’s head. He wears a nice suit, carries a guitar case—and has a magic curse written on his skin that attracts unwanted attention from wealthy white people and the cops. And then Tom delivers a page of occult writing to a sorceress who lives in the heart of Queens, and winds up awakening something that was better left sleeping.

Here’s an excerpt from “Ballad of Black Tom,” which will be released on February 16:

1

People who move to New York always make the same mistake. They can’t see the place. This is true of Manhattan, but even the outer boroughs, too, be it Flushing Meadows in Queens or Red Hook in Brooklyn. They come looking for magic, whether evil or good, and nothing will convince them it isn’t here. This wasn’t all bad, though. Some New Yorkers had learned how to make a living from this error in thinking. Charles Thomas Tester for one.

The morning of most importance began with a trip from Charles’s apartment in Harlem. He’d been hired to make a delivery to a house out in Queens. He shared the crib in Harlem with his ailing father, Otis, a man who’d been dying ever since his wife of twenty-one years expired. They’d had one child, Charles Thomas, and even though he was twenty and exactly the age for independence, he played the role of dutiful son. Charles worked to support his dying dad. He hustled to provide food and shelter and a little extra to lay on a number from time to time. God knows he didn’t make any more than that.

A little after 8:00 a.m., he left the apartment in his gray flannel suit; the slacks were cuffed but scuffed and the sleeves conspicuously short. Fine fabric, but frayed. This gave Charles a certain look. Like a gentleman without a gentleman’s bank account. He picked the brown leather brogues with nicked toes. Then the seal-brown trooper hat instead of the fedora. The trooper hat’s brim showed its age and wear, and this was good for his hustle, too. Last, he took the guitar case, essential to complete the look. He left the guitar itself at home with his bedridden father. Inside he carried only a yellow book, not much larger than a pack of cards.

As Charles Thomas Tester left the apartment on West 144th Street, he heard his father plucking at the strings in the back bedroom. The old man could spend half a day playing that instrument and singing along to the radio at his bedside. Charles expected to be back home before midday, his guitar case empty and his wallet full.

“Who’s that writing?” his father sang, voice hoarse but the more lovely for it. “I said who’s that writing?”

Before leaving, Charles sang back the last line of the chorus. “John the Revelator.” He was embarrassed by his voice, not tuneful at all, at least when compared with his dad’s.

In the apartment Charles Thomas Tester went by Charles, but on the street everyone knew him as Tommy. Tommy Tester, always carrying a guitar case. This wasn’t because he aspired to be a musician; in fact he could barely remember a handful of songs and his singing voice might be described, kindly, as wobbly. His father, who’d made a living as a bricklayer, and his mother, who’d spent her life working as a domestic, had loved music. Dad played guitar and Mother could really stroll on a piano. It was only natural that Tommy Tester ended up drawn to performing, the only tragedy being that he lacked talent. He thought of himself as an entertainer. There were others who would have called him a scammer, a swindler, a con, but he never thought of himself this way. No good charlatan ever did.

In the clothes he’d picked, he sure looked the part of the dazzling, down-and-out musician. He was a man who drew notice and enjoyed it. He walked to the train station as if he were on his way to play a rent party alongside Willie “The Lion” Smith. And Tommy had played with Willie’s band once. After a single song Willie threw Tommy out. And yet Tommy toted that guitar case like the businessmen proudly carrying their briefcases off to work now. The streets of Harlem had gone haywire in 1924, with blacks arriving from the South and the West Indies. A crowded part of the city found itself with more folks to accommodate. Tommy Tester enjoyed all this just fine. Walking through Harlem first thing in the morning was like being a single drop of blood inside an enormous body that was waking up. Brick and mortar, elevated train tracks, and miles of underground pipe, this city lived; day and night it thrived.

Tommy took up more room than most because of the guitar case. At the 143rd Street entrance he had to lift the case over his head while climbing the stairs to the elevated track. The little yellow book inside thumped but didn’t weigh much. He rode all the way down to 57th Street and there transferred for the Roosevelt Avenue Corona Line of the BMT. It was his second time going out to Queens, the first being when he’d taken the special job that would be completed today.

The farther Tommy Tester rode into Queens the more conspicuous he became. Far fewer Negroes lived in Flushing than in Harlem. Tommy bumped his hat slightly lower on his head. The conductor entered the car twice, and both times he stopped to make conversation with Tommy. Once to ask if he was a musician, knocking the guitar case as if it were his own, and the second time to ask if Tommy had missed his stop. The other passengers feigned disinterest even as Tommy saw them listening for his replies. Tommy kept the answers simple: “Yes, sir, I play guitar” and “No, sir, got a couple more stops still.” Becoming unremarkable, invisible, compliant—these were useful tricks for a black man in an all-white neighborhood. Survival techniques. At the last stop, Main Street, Tommy Tester got off with all the others—Irish and German immigrants mostly—and made his way down to street level. A long walk from here.

The whole way Tommy marveled at the broad streets and garden apartments. Though the borough had grown, modernized greatly since its former days as Dutch and British farmland, to a boy like Tommy, raised in Harlem, all this appeared rustic and bewilderingly open. The open arms of the natural world worried him as much as the white people, both so alien to him. When he passed whites on the street, he kept his gaze down and his shoulders soft. Men from Harlem were known for their strut, a lion’s stride, but out here he hid it away. He was surveyed but never stopped. His foot-shuffling disguise held up fine. And finally, amid the blocks and blocks of newly built garden apartments, Tommy Tester found his destination.

A private home, small and nearly lost in a copse of trees, the rest of the block taken up by a mortuary. The private place grew like a tumor on the house of the dead. Tommy Tester turned up the walkway and didn’t even have to knock. Before he’d climbed the three steps, the front door cracked open. A tall, gaunt woman stood in the doorway, half in shadows. Ma Att. That was the name he had for her, the only one she answered to. She’d hired him like this. On this doorstep, through a half-open door. Word had traveled to Harlem that she needed help and he was the type of man who could acquire what she needed. Summoned to her door and given a job without being invited in. The same would happen now. He understood, or could at least guess, at the reason. What would the neighbors say if this woman had Negroes coming freely into her home?

Tommy undid the latch of the guitar case and held it open. Ma Att leaned forward so her head peeked out into the daylight. Inside lay the book, no larger than the palm of Tommy’s hand. Its front and back covers were sallow yellow. Three words had been etched on both sides. Zig Zag Zig. Tommy didn’t know what the words meant, nor did he care to know. He hadn’t read this book, never even touched it with his bare hands. He’d been hired to transport the little yellow book, and that was all he’d done. He’d been the right man for this task, in part, because he knew he shouldn’t do any more than that. A good hustler isn’t curious. A good hustler only wants his pay.

Ma Att looked from the book, there in the case, and back to him. She seemed slightly disappointed.

“You weren’t tempted to look inside?” she asked.

“I charge more for that,” Tommy said.

She didn’t find him funny. She sniffled once, that’s all. Then she reached into the guitar case and slipped the book out. She moved so quickly the book hardly had a chance to catch even a single ray of sunlight, but still, as the book was pulled into the darkness of Ma Att’s home, a faint trail of smoke appeared in the air. Even glancing contact with daylight had set the book on fire. She slapped at the cover once, snuffing out the spark.

“Where did you find it?” she asked.

“There’s a place in Harlem,” Tommy said, his voice hushed. “It’s called the Victoria Society. Even the hardest gangsters in Harlem are afraid to go there. It’s where people like me trade in books like yours. And worse.”

Here he stopped. Mystery lingered in the air like the scent of scorched book. Ma Att actually leaned forward as if he’d landed a hook into her lip. But Tommy said no more.

“The Victoria Society,” she whispered. “How much would you charge to take me in?”

Tommy scanned the old woman’s face. How much might she pay? He wondered at the sum, but still he shook his head. “I’d feel terrible if you got hurt in there. I’m sorry.”

Ma Att watched Tommy Tester, calculating how bad a place this Victoria Society could be. After all, a person who trafficked in books like the little yellow one in her hand was hardly the frail kind.

Ma Att reached out and tapped the mailbox, affixed to the outside wall, with one finger. Tommy opened it to find his pay. Two hundred dollars. He counted through the cash right there, in front of her. Enough for six months’ rent, utilities, food and all.

“You shouldn’t be in this neighborhood when the sun goes down,” Ma Att said. She didn’t sound concerned for him.

“I’ll be back in Harlem before lunchtime. I wouldn’t suggest you visit there, day or night.” He tipped his cap, snapped the empty guitar case shut, and turned away from Ma Att’s door.

On the way back to the train, Tommy Tester decided to find his friend Buckeye. Buckeye worked for Madame St. Clair, the numbers queen of Harlem. Tommy should play Ma Att’s address tonight. If his number came up, he’d have enough to buy himself a better guitar case. Maybe even his own guitar.

2

“That’s a fine git-fiddle.”

Tommy Tester didn’t even have to look up to know he’d found a new mark. He simply had to see the quality of the man’s shoes, the bottom end of a fine cane. He plucked at his guitar, still getting used to the feel of the new instrument, and hummed instead of sang because he sounded more like a talented musician when he didn’t open his mouth.

The trip out to Queens last month had inspired Tommy Tester to travel more. The streets of Harlem could get pretty crowded with singers and guitar players, men on brass instruments, and every one of them put his little operation to shame. Where Tommy had three songs in his catalog, each of those men had thirty, three hundred. But on the way home from Ma Att’s place, he’d realized he hadn’t passed a single strummer along the way. The singer on the street might’ve been more common in Harlem and down in Five Points, or more modern parts of Brooklyn, but so much of this city remained—essentially—a bit of jumped-up countryside. None of the other Harlem players would take a train out to Queens or rural Brooklyn for the chance of getting money from the famously thrifty immigrants homesteading in those parts. But a man like Tommy Tester—who only put on a show of making music—certainly might. Those outer-borough bohunks and Paddys probably didn’t know a damn thing about serious jazz, so Tommy’s knockoff version might still stand out.

On returning from Ma Att’s place, he’d talked all this through with his father. Otis Tester, yet one more time, offered to get him work as a bricklayer, join the profession. A kind gesture, a loving father’s attempt, but not one that worked on his son. Tommy Tester would never say it out loud—it’d hurt the old man too much—but working construction had given his father gnarled hands and a stooped back, nothing more. Otis Tester had earned a Negro’s wage, not a white man’s, as was common in 1924, and even that money was withheld if the foreman sometimes wanted a bit more in his pocket. What was a Negro going to do? Complain to whom? There was a union, but Negros weren’t allowed to join. Less money and erratic pay were the job. Just as surely as mixing the mortar when laborers didn’t show up to do it. The companies that’d hired Otis Tester, that’d always assured him he was one of them, had filled his job the same day his body finally broke down. Otis, a proud man, had tried to instill a sense of duty in his only child, as had Tommy’s mother. But the lesson Tommy Tester learned instead was that you better have a way to make your own money because this world wasn’t trying to make a Negro rich. As long as Tommy paid their rent and brought home food, how could his father complain? When he played Ma Att’s number, it hit as he dreamed it would, and he bought a fine guitar and case. Now it was common for Tommy and Otis to spend their evenings playing harmonies well into the night. Tommy had even become moderately better with a tune.

Tommy had decided against a return to Flushing, Queens, though. A hustler’s premonition told him he didn’t want to run into Ma Att again. After all, the book he’d given her had been missing one page, hadn’t it? The very last page. Tommy Tester had done this with purpose. It rendered the tome useless, harmless. He’d done this because he knew exactly what he’d been hired to deliver. The Supreme Alphabet. He didn’t have to read through it to be aware of its power. Tommy doubted very much the old woman wanted the little yellow book for casual reading. He hadn’t touched the book with his bare hands and hadn’t read a single word inside, but there were still ways to get the last sheet of parchment free safely. In fact that page remained in Tommy’s apartment, folded into a square, slipped right inside the body of the old guitar he always left with his father. Tommy had been warned not to read the pages, and he’d kept to that rule. His father had been the one to tear out the last sheet, and his father could not read. His illiteracy served as a safeguard. This is how you hustle the arcane. Skirt the rules but don’t break them.

Today Tommy Tester had come to the Reformed Church in Flatbush, Brooklyn; as far from home as Flushing, and lacking an angry sorceress. He wore the same outfit as when he went to visit Ma Att, his trooper hat upside down at his feet. He’d set himself up in front of the church’s iron-railed graveyard. A bit of theater in this choice, but the right kind of person would be drawn to this picture. The black jazz man in his frayed dignity singing softly at the burying ground.

Tommy Tester knew two jazz songs and one bit of blues. He played the blues tune for two hours because it sounded more somber. He didn’t bother with the words any longer, only the chords and a humming accompaniment. And then the old man with the fine shoes and the cane appeared. He listened quietly for a time before he spoke.

“That’s a fine git-fiddle,” the man finally said.

And it was the term—git-fiddle—that assured Tommy his hustle had worked. As simple as that. The old man wanted Tommy to know he could speak the language. Tommy played a few more chords and ended without flourish. Finally he looked up to find the older man flushed, grinning. The man was round and short, and his hair blew out wildly like a dandelion’s soft white blowball. His beard was coming in, bristly and gray. He didn’t look like a wealthy man, but it was the well-off who could afford such a disguise. You had to be rich to risk looking broke. The shoes verified the man’s wealth, though. And his cane, with a handle shaped like an animal head, cast in what looked like pure gold.

“My name is Robert Suydam,” the man said. Then waited, as if the name alone should make Tommy Tester bow. “I am having a party at my home. You will play for my guests. Such dusky tunes will suit the mood.”

“You want me to sing?” Tommy asked. “You want to pay me to sing?”

“Come to my home in three nights.”

Robert Suydam pointed toward Martense Street. The old man lived there in a mansion hidden within a disorder of trees. He promised Tommy five hundred dollars for the job. Otis Tester had never made more than nine hundred in a year. Suydam took out a billfold and handed Tommy one hundred dollars. All ten-dollar bills.

“A retainer,” Suydam said.

Tommy set the guitar flat in its case and accepted the bills, turning them over. 1923 bills. Andrew Jackson appeared on the front. The image of Old Hickory didn’t look directly at Tommy, but glanced aside as if catching sight of something just over Tommy Tester’s right shoulder.

“When you arrive at the house, you must say one word and only this word to gain entrance.”

Tommy stopped counting the money, folded it over twice, and slipped it into the inner pocket of his jacket.

“I can’t promise what will happen if you forget it,” Suydam said, then paused to watch Tommy, assessing him.

“Ashmodai,” Suydam said. “That is the word. Let me hear you say it.”

“Ashmodai,” Tommy repeated.

Robert Suydam tapped the cane on the pavement twice and walked away. Tommy watched him go for three blocks before he picked up his hat and put it on. He clicked the guitar case shut. But before Tommy Tester took even one step toward the train station, he got gripped, hard, on the back of the neck.

Two white men appeared. One was tall and thin, the other tall and wide. Together they resembled the number 10. The wide one kept his hand on Tommy’s neck. He knew this one was a cop, or had been once. Up in Harlem they called this grip John’s Handshake. The thin one stayed two paces back.

The surprise of it all caused Tommy to forget the pose of deference he’d normally adopt when cops stopped him. Instead he acted like himself, his father’s son, a kid from Harlem, a proud man who didn’t take kindly to being given shit.

“You’re coming on a little strong,” he told the wide one.

“And you’re far from home,” the wide one replied.

“You don’t know where I live,” Tommy snapped back.

The wide one reached into Tommy’s coat and removed the ten-dollar bills. “We saw you take these from the old man,” he began. “That old man is part of an ongoing investigation, so this is evidence.”

He slipped the bills into his slacks and watched Tommy to gauge his reaction.

“Police business,” Tommy said coolly, and stopped thinking that the money had ever been his.

The wide one pointed at the thin one. “He’s police. I’m private.”

Tommy looked from the private detective to the cop. Tall and thin and lantern-jawed, his eyes dispassionate and surveying. “Malone,” he finally offered. “And this is . . .”

The wide one cut him off. “He doesn’t need my name. He didn’t need yours, either.”

Malone looked exasperated. This strong-arm routine didn’t seem like his style. Tommy Tester read both men quickly. The private detective had the bearing of a brute while the other one, Malone, appeared too sensitive for a cop’s job. Tommy considered that he’d stayed a few paces back to keep away from the private dick, not Tommy.

“What’s your business with Mr. Suydam?” the private detective asked. He pulled Tommy’s hat off and looked inside as if there might be more money.

“He liked my music,” Tommy said. Then, calm enough now to remember the situation, he added another word quickly. “Sir.”

“I heard your voice,” the private detective said. “Nobody could enjoy that.”

Tommy Tester would’ve liked to argue the point, but even a corrupt, violent brute could be right sometimes. Robert Suydam wasn’t paying five hundred dollars for Tommy’s voice. For what, then?

“Now me and Detective Malone are going to keep strolling with Mr. Suydam, keeping him safe. And you’re going to go back home, isn’t that right? Where’s home?”

“Harlem,” Tommy offered. “Sir.”

“Of course it is,” Malone said quietly.

“Home to Harlem, then,” the private detective added. He set the hat back on Tommy’s head and gave Malone a quick, derisive glance. He turned in the direction where the old man had gone, and only then did Malone step any closer to Tommy. Standing this near, Tommy could sense a kind of sadness in the gaunt officer. His eyes suggested a man disappointed with the world.

Tommy waited before reaching down for his guitar case. No sudden moves in front of even a sullen cop. Just because Malone wasn’t as rough as the private detective didn’t mean he was gentle.

“Why did he give you that money?” Malone asked. “Why really?”

He asked, but seemed to doubt an honest answer would come. Instead there was a set to his lips, and a narrowness in his gaze, that suggested he was probing for an answer to some other question. Tommy worried he’d mention the performance at Suydam’s home in three nights. If they weren’t happy about Tommy talking with Suydam on the street, how would they act upon learning he planned to visit the old man’s home? Tommy lost one hundred dollars to the private detective, but he was damned if he’d give up the promise of four hundred dollars more. He decided to play a role that always worked on whites. The Clueless Negro.

“I cain’t says, suh,” Tommy began. “I’s just a simple geetar man.”

Malone came close to smiling for the first time. “You’re not simple,” he said.

Tommy watched Malone walk off to catch up with the private detective. He looked over his shoulder. “And you’re right to stay out of Queens,” Malone said. “That old woman isn’t happy with what you did to her book!”

Malone walked off and Tommy Tester remained there, feeling exposed—seen—in a way he’d never experienced.

“You’re a cop,” Tommy called. “Can’t you protect me?”

Malone looked back once more. “Guns and badges don’t scare everyone.”

And here’s the cover art without any words over it:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.