The basic structure of the human brain has remained essentially unaltered for tens of thousands of years, but the information processed within it has changed dramatically over time. Today, we require an entirely new set of skills to get by, but at the expense of our ancient know-how. Here are some essential skills used by our ancestors to survive—but which we’ve now forgotten.

Aside from a precious few who have gone out of their way to learn basic survival skills, most of us today would be utterly hopeless if we were plopped in the middle of a forest or jungle and suddenly forced to fend for ourselves using only the resources around us. To our ancient ancestors, we’d appear as helpless as babies.

In all fairness, however, we’ve failed to retain these skills simply due to the fact that we don’t need them anymore. We’re required to learn other things to survive our modern lives, like how to make a steady income, take the subway home from work, and do our taxes. But it would be a mistake to think that our paleolithic ancestors weren’t as sophisticated or innovative in their thinking. Without a doubt, they didn’t have the voluminous depth and breadth afforded to us by our acquired knowledge, but they did have the same brains. And they used those brains to do some rather remarkable things.

Thousands of years later, it’s difficult to piece together the details of these forgotten skills. Thanks to the work of archaeologists and anthropologists, however, we’re starting to put together a picture of what our distant ancestors knew, and how they applied this knowledge to survive daily life. Scientists are also conducting comparative analyses of relatively recent stone age cultures and so-called “lost tribes” to gain an appreciation for what life was like tens of thousands of years ago.

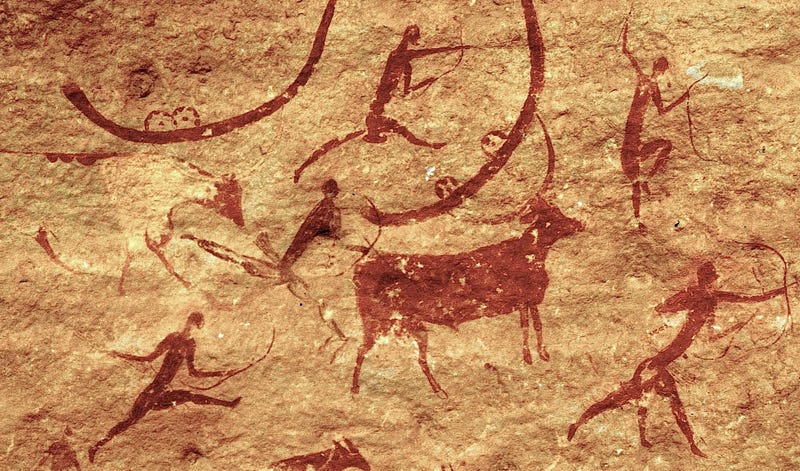

Saharan rock art (Credit: Gruban/CC BY-SA 2.0)

To help me learn more about these forgotten survival skills, I recruited the help of Klint Janulis, an anthropologist who’s currently completing a doctoral program in prehistoric archaeology at the University of Oxford. Janulis, a former U.S. Army Special Forces Operator and primitive skills survival instructor, is studying the relationship between human cognition and subsistence. He’s also a consultant and onscreen expert for the U.K. based television show 10,000 BC and lead instructor for the University of Colorado’s Center for Cognitive Archaeology experimental field school.

“Many technologies useful for individual survival have been replicated by anthropologists, and while we obviously won’t ever know the full spectrum of stone age technological innovation, we can reasonably speculate and experiment with many of them,” says Janulis.

Tracking and Hunting Animals

“Tracking animals is a significant skill that likely developed very early in our history as we developed greater cognitive abilities and became more reliant on animal fats and proteins to feed our big brains,” says Janulis.

He pointed me to the work of Louis Leibenberg, a researcher from the University of Harvard who says that tracking was a critical step in human evolution. Leibenberg makes the case that the art of tracking involves the same intellectual and creative abilities as physics and mathematics, and may very well represent the origin of science itself.

Anthropologists also suspect that humans began tracking animals before they started hunting. “The identification of prides of large cats, or sign of scavengers like hyenas could bring you close to where a possible kill site is and potential scavenging opportunities of either meat or valuable marrow from the bones or even places you want to avoid,” Janulis says.

A spear thrower of the Maasai People (Credit: David Berkowitz/CC BY-2.0)

Neil Roach, now at George Washington University, has even suggested that the evolved human aptitude for throwing— a skill not shared with other primates—stems from a need to be able to throw stones to either hunt or scare away predators from a kill

More recently, Lyn Wadley from the University of the Witwatersrand has analyzed the remains of animals found in a South African cave site called Sibudu. Evidence suggests that snares may have been used as far back as 77,000 years, and bows and arrows 61,000 years ago.

“Most hunter-gatherers today grow up tracking from birth and become keen observers of nuances of animal behaviour that would be completely missed by most people who haven’t been raised in that manner,” says Janulis. “The devil is in the details as they say, and by being able to read the subtle nuances such as the size of the animal, gender, and likely future behaviour, you can put together a much more complete picture of your hunting environment and much more successfully position yourself to have a successful hunt.”

Knowing What to Eat and How to Medicate

Janulis says that the knowledge of edible and medicinal foods would have been passed on over many generations, and that this detailed knowledge is one of the biggest losses to the world in terms of forgotten survival skills.

The seeds of the jequirity plant look tasty. Too bad they’ll kill you—it contains the abrin protein, one of the most lethal known botanical toxins. (credit: Forest & Kim Starr/Public domain)

“That accumulated knowledge of the plant world not only was specific to each ecosystem, but would have contained the nuances of conditions, appearance, and preparation that those of us who study survival and ethnobotany can’t hope to fully replicate without that generational knowledge guiding us,” he says.

Today, the best thing we have when confronted with a similar situation is the so-called “universal edibility test.” This rather imperfect test involves the graduated introduction of a given plant to the body in a series of steps. It starts by placing the plant on the skin, and then introducing it to an abraded area, then lips, tongue, and finally a small amount of consumption. Between each step, the person is supposed to wait and assess their reaction to the plant.

“This method is debated as some plants have chemicals that have a delayed onset reaction and it may take much more time for the toxins to harm you than the test allows, particularly with fungus,” says Janulis.

In regards to medicine, it’s worth noting that some degree of self medication has been observed in other primates as well

Navigational Skills

There’s no question that our early ancestors travelled great distances without the benefit of highly detailed maps or GPS. Archaeologists can get a sense of how far these people traveled from their shelter sites by tracing the sources of the stone used to craft their tools. By the Middle Paleolithic era, humans were capable of travelling or trading within hundreds of miles from the locations where they were living.

Does anyone know where we’re going? (Credit: McKay Savage/CC AB-2.o)

“This implies the ability to navigate, says Janulis, adding that humans have the added aptitude for distance running—a trait that’s been around since the time of Homo erectus some 1.8 million years ago. He says this ability would have been useful not just in persistence hunting, but also in hitting remote foraging spots efficiently.

“If humans were running animals down either through fatigue or a combination of human caused injury and fatigue, the implied ability associated with that would be navigation and the ability to find one’s way back,” he says.

Work by Thomas Wynn of the University of Colorado Center for Cognitive Archaeology suggests that modern spatial cognition was in place as far back as 500,000 years ago, and was likely used for navigation.

“While humans have an excellent and clearly developed sense of spatial cognition and mental map making, modern humans from all cultures still rely on navigation aids while out in the wilderness or even just in slightly unfamiliar terrain,” Janulis says. “Native Americans were recorded to leave waypoint markers in the form of either artwork, rock cairns or bent over trees pointing in an appropriate direction to aid them.”

Janulis also points to indigenous Australians, who used a combination of pictographic maps, storytelling, and artwork to navigate the vast and often featureless Australian outback. The maps and landscape were interwoven with the storytelling into a complex system that not only gave meaning and history to the landscape, but also aided in navigation.

Cordage, i.e. ropes and cords, and shell spiderweb style maps made by the indigenous sailors of Micronesia conveyed relative distance to different islands and also directions of the safest approach to each island represented by a shell. These ancient sailors used the maps in conjunction with highly developed skills and technique to navigate waters that still challenge modern sailors, says Janulis. Indeed, the 24 major island groups of the Pacific Ocean were settled by early Austronesians between 3,500 and 900 years ago, but we still know very little about how these isolated islands were colonized

The study of indigenous North Americans provide another incredible glimpse of early navigational capabilities.

“It was observed by Colonel Richard Dodge of the U.S. Army in the 19th century that when young Apache men were coming of age, they would be expected to travel several hundred miles to raid a village that they had never been too,” notes Janulis. “They were able to memorize the route through the use of a mnemonic aid in the form of sticks with notches cut on them. The elders of the village would sit around a fire and tell them the route and at each major turn, they would cut a notch in the stick that represented the change in direction.”

Remarkably, Janulis says the young men would read back the directions as they slid their fingers over the notches, and by using the tactile association with the notches, they would be able to more easily recall the directions they were being given.

“What this tells us is that despite our navigation ability and our evolved working memory capacity, the real ‘survival skill’ in this sense is that we learned to offload that working memory burden onto material goods that could store that data for us,” Janulis says. “That is the bit of our evolved brains that has probably had the most significant impact on our success as a species and is seen in everything ranging from early bead counters to modern smartphones that all cognitively do the same job for us.”

Making Clothes from Scratch

Clothes varied from region to region depending on the climate and the resources available. The methods used for clothing manufacture were only limited by the properties of the materials being used, and the creativity of the manufacturer.

“What we see among modern or recorded hunter-gatherer populations is a reflection of that sort of unlimited diversity with clothes made of everything from traditional leather to woven palm leaf technologies or highly processed cedar tree bark,” says Janulis.

Consider Otzi the Iceman, a 5,300-year-old human found embedded in a glacier in the Austrian Alps. His immaculately preserved remains offered archaeologists and anthropologists some indication as to how humans in prehistoric Europe may have dressed. Otzi was found with sewn garments of a variety of different leathers, each of them with different properties and purposes.

A replica of Otzi’s shoe (credit: Josef Chlachula/CC BY-SA 3.0)

“For instance, the soles of his shoes were comprised of thick bear skin, while the tops of his shoes were softer deer hide and the inside was a bark mesh,” notes Janulis. “Additionally his cloak was made of woven grass which would have been waterproof and could have doubled as a bed mat to insulate him from the ground or a cover.”

Scientists know that, by the middle Paleolithic/Middle Stone Age, humans were hunting, and were likely making containers and cordage. This implies that they would have had a wide range of technologies with which to make clothing beyond just animal hides stitched together. As humans moved into Europe and colder areas, clothing technology would have had to have been reasonably well developed just to survive.

Group Survival

Janulis says the biggest lost skill for survival is not any one technique or prehistoric craft, but instead the loss of culturally and generationally developed subsistence patterns specific to an environment.

“Warriors in ambush” — an Aboriginal Bora Ceremony (credit: Kerry & Co./Public domain)

“This basically means that a hypothetical hunter-gatherer or modern group dropped into a new ecosystem would have to redevelop an efficient subsistence pattern based on the nuances of their new environment, but with very little culturally transmitted knowledge guiding them,” he says.

Indeed, this hypothetical group would first have to work out what the biggest nutritional resources are in the area, the most efficient way to hunt or gather them, how to process them and—most importantly—where they should be prioritizing their efforts. A hunter-gatherer who had been raised to keenly observe the natural world and identify animal behaviour would be able to adapt to this change in ecosystem by employing their already developed powers of observation, deduction, and intuition in that process.

Urbanized modern humans, on the other hand, would not only be fighting their lack of knowledge of the new ecosystem, but also their lack of skill, observational powers and awareness which would likely lead them to grossly misplaced priorities and efforts. For urbanized humans trapped in a primitive survival situation, the only solution for this would be strong leadership who understands group survival dynamics.

“This leader would not need to be the strongest or best hunter, but someone who could systematically employ the efforts of their group in a manner that efficiently brings in the easiest to gather nutritional resources, while experimentally learning how to acquire the harder ones,” says Janulis.

The Real Survival Skill

On a related note, Janulis points out that these skills weren’t “survival skills” as we regard them today, but rather the realities of everyday life.

This is a point his primitive skills mentor John McPherson of Prairie Wolf survival also likes to emphasize: “These early humans didn’t live in some constant survival film, they were born into a material culture of goods and skills that were taught from an early age. They would have had neighboring tribes and interwoven social connections with other groups that they could rely on when things went bad.” Janulis adds that what differentiates most modern people from our ancestors is our upbringing and our way of thinking.

“The Historian” - The artist is painting in sign language, on buckskin, the story of a battle with American Soldiers. (Credit: E. Irving Couse/Public domain)

Indeed, the ability of Micronesian sailors or Bushmen to navigate challenging situations with seemingly little effort may appear to us as some sort of inherent ability that people in the modern world lack, but as Janulis points out, “there are no magical bushmen.” Rather, they have a way of looking at the world and learning the properties of their environment that we don’t often have.

As Louis Leibenberg notes in his book The Art of Tracking, Kalahari children grow-up learning how to track insects and lizards, and read their signs in order to hunt them with small bows. Janulis says this sort of training is invaluable as it prepares them mentally for identifying the nuances of the animal behaviour and the signs they leave behind.

What’s more, groups that live in difficult environments are going to be very attuned to subtle changes in the terrain that will tell them such things as proximity to water, or a slight change in climate that would be missed by many modern people. These nuances are constantly informing them as they hunt or navigate in a way that many of us don’t see.

Finally, Janulis says there’s another thing modern people lack—the habit of group storytelling where we share our experiences and tales of things we have observed.

“This would have been a valuable way for small groups to share new knowledge and observations in a way that it has a cumulative effect that benefits the group,” he says. “Recently though, with the advent of the internet and social media, it has made it much easier for us to share those stories and experiences within specialized online realms. So many of these skills are making a comeback as the primitive technology and archaeological communities can quickly and easily benefit from the mistakes and successes of others, and learning processes in a way that was not possible since we lived in hunter-gatherer bands.”

This ability to transmit experiences and knowledge effectively, argues Janulis, may have even influenced human lifespans by selecting for population groups whose elders were around longer to advise and aid.

Citations: Louis Liebenberg: “The Art of Tracking, the Origin of Science” | Laura Spinney: “Lethal weapons and the evolution of civilization” | Dietrich Stout et al., “Late Acheulean technology and cognition at Boxgrove, UK” | Lucinda Blackwell et al., “Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa” | Thomas Wynn: “Symmetryy and the evolution of the modular linguistic mind.”

You can follow Klint on twitter at @klintjanulis.