On October 12th, 1983, Bill Landreth called his friend Chris in Detroit to chat. Chris frantically explained that the FBI had raided his house. “Don’t call me anymore,” Chris said in what would be a very short conversation. Bill didn’t know exactly what was happening, but he did know this: If the FBI had come for Chris, then he might be next.

The next day, around a dozen FBI agents stormed Bill’s parent’s house just outside of San Diego, amassing piles of evidence including a computer that Bill, then 18, had hidden under his sister’s bed. Bill and Chris, who was 14 at the time, were the leaders of a coalition of teen hackers known as The Inner Circle. In a single day, the FBI conducted coordinated raids of group members across nine states, taking computers, modems, and copious handwritten notes detailing ways to access various networks on what was then a rudimentary version of the internet.

The Inner Circle was a motley group of about 15 hackers, almost all teenagers, from Southern California, Detroit, New York, and roughly five other regions of the US. Bill, Chris, and other members of their collective had been accessing all kinds of networks, from GTE’s Telemail—which hosted email for companies like Coca-Cola, Raytheon, Citibank, and NASA—to the Arpanet, which was largely used by university researchers and military personnel until Milnet was completed in the mid-1980s. Chris was fond of boasting on message boards about hacking the Pentagon. The Inner Circle wasn’t the only teen hacking group of the early 1980s, but their interference with both government networks and the email accounts of large corporations put them on the FBI’s radar. Along with the 414s, a group busted around the same time, the raids made national headlines. The Inner Circle’s actions would inspire a complete overhaul in how computer crime was prosecuted, through the introduction of the country’s first anti-hacking laws in 1984.

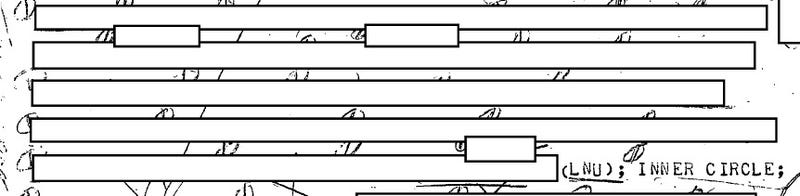

I decided to track down members of The Inner Circle, and find out what happened during their heyday and infamous bust, and where it’s led them today. In the process, I’ve obtained 351 pages of FBI documents about early-80s teen hacker communities through a Freedom of Information Act request. The pages are heavily redacted, but they fill in some of the many holes that remain about The Inner Circle, the FBI’s crash course in computers, and the teen computer underground of the early 1980s.

The story of Bill and Chris is one of simple curiosity, and the birth of the modern internet in an era before computer hacking laws existed. It was an era when most of America—including virtually everyone in the FBI—couldn’t tell you what a modem was. This period, from roughly 1979 until 1983, was a mythical Wild West for kids who became interested in computers, and saw the rising popularity (and declining price) of personal computers as well as the release of the movie Wargames. The kids of this period were early adopters, and they got into plenty of trouble.

After WarGames came out in June 1983, every wannabe hacker with more money than sense went out and got a computer and modem from places like RadioShack, thinking they could get their fingers close to the big red button. It didn’t work that way, of course. But there were plenty of other hijinks that kids of the early 1980s could pull with a computer, a phone line, and the special brand of fearlessness that comes with youth.

The FBI started tracking The Inner Circle in 1982, but it wasn’t until late 1983 that they’d finally bust the group. In large part, that bust was possible because of a 42-year-old pseudo-vigilante hacker known as John Maxfield—a former phone phreak who fancied himself the proto-internet’s sheriff. Maxfield gained the trust of teen hacker communities on bulletin board systems (BBSs) in the early 1980s and fed the information to the FBI.

Maxfield provided the FBI with the intelligence they needed on The Inner Circle’s exploits, especially when it came to the hacking of Telenet’s Telemail email system. Chris, frustrated and bored, had started deleting emails of Coca-Cola executives and using administrator passwords to change the names on accounts. GTE, the company that operated the Telemail service, wasn’t pleased. After all, the hackers were using Telemail “illegally.” Which is to say, for free. FBI documents spell out just how much time was being stolen by these kids, right down to the penny. For example, use of BMW’s messaging service by unauthorized users in September, 1983, cost GTE $0.29. Unauthorized use of Raytheon’s accounts in the same month totaled $298. But it was the widespread loss of faith in the system’s security that was most damaging to GTE.

I spoke with Bill and Chris, but was unable to connect with any other of The Inner Circle members or Maxfield. A letter sent to Maxfield’s last known PO Box has yet to receive a reply, and the last known number I could find for him was disconnected. For all I know, he’s dead. Or he’s elderly and keeping a low profile. Maxfield always tried to stay off the radar, but after he was exposed as an FBI informant in late 1983, he became the most loathed man on the internet.

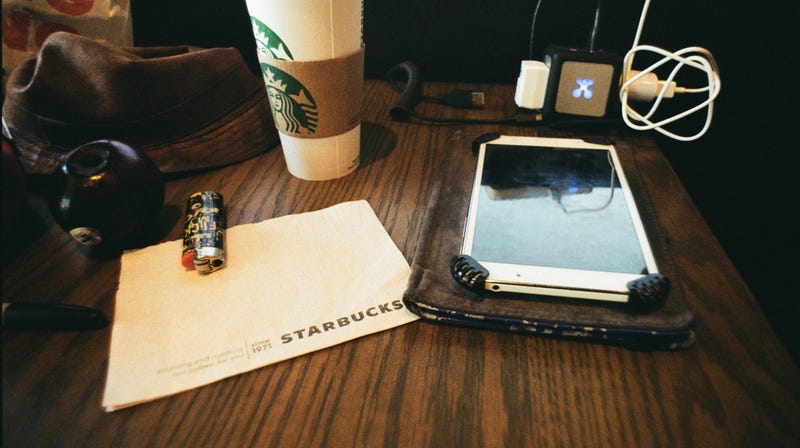

When I met Bill Landreth at a Starbucks in Santa Monica, he was sitting quietly at a table drinking coffee with two bags on the the seat across from him, and a bag of blankets in the corner. A pipe made out of an apple and filled with what I assumed was medical marijuana sat at the table next to his coffee and Samsung tablet. A passing cop glanced at the spread but didn’t raise an eyebrow.

Arranging our meeting was tricky, because Bill isn’t sure where he’ll be sleeping from night to night. Now 52, with a slight goatee and a tussle of wavy hair that nearly reaches his shoulders, Bill has been living on the streets for 30 years. But if it weren’t for his receding hairline and a certain grayness to his gaze, he’d probably pass for a decade younger. There’s something assertive yet firmly guarded about the way he speaks. It’s as though Bill’s a man who’s not afraid to say what he thinks, but still worries about saying something out of line in front of me.

In our conversation, he was calm, affable, and clearly intelligent, and almost immediately began rattling off computers and computing languages of which I have little to no background or understanding.

Bill got his first computer in 1980, he tells me. It was a TRS-80 from RadioShack. He was 14 or 15, and explains that he planned to get the version with 8K of memory using $500 he had saved. His dad offered to pitch in another $500, and he got the 16K version with a cassette tape drive for storage. He also picked up a 300 baud modem.

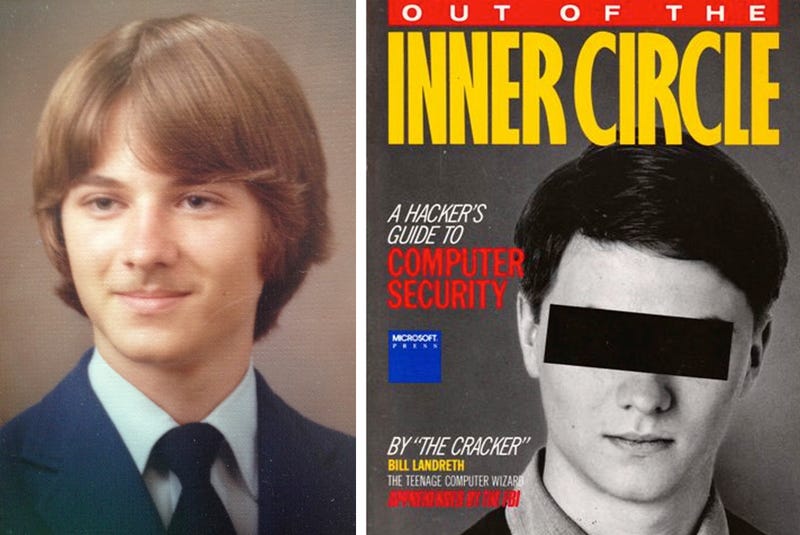

Bill was a quick learner, and developed a knack for the BASIC programming language. From there he’d learn other languages, and his desire to explore the world of computing became overpowering. After he’d conquered one area, there was always something new around the corner. He was an explorer; more interested in mapping the entire terrain than in penetrating deep into any given network. Bill, who would take up the moniker The Cracker, found community with an emerging group of misfits online. They gave him a sense of place in the new world he was traversing.

“You didn’t really meet many of the other people,” Bill says. “You could go out of your way to try to.” But Bill’s connections were through his modem and phone.

He’s the son of two hippies who spent much of his childhood living a semi-nomadic lifestyle. His dad, an astronomy lover, built telescopes under the brand name Essential Optics. But he only charged people for parts at cost, and hardly charged anything for his labor. The only moderate business success Bill’s father ever had was selling grow lamps in the 1970s. He even bought full page ads for the lamps (ostensibly to grow tomatoes) in High Times magazine.

Despite his friend Chris’s warning on October 12, 1983, Bill wasn’t sure that the FBI was coming for him when they did. Aside from his grow-lamp business, Bill’s dad had a tendency to go up to Big Bear (a rural, touristy area about four hours outside of LA) to pick up LSD and cocaine. To this day, Bill’s still not convinced that there wasn’t some attempt by the FBI to get at his father through him.

But they had come for Bill. Along with other teenage nerds in his collective, Bill was “hacking” the first commercial packet-switched network, Telenet. The Telenet network (now owned by Raytheon) was inspired by the structure of the Arpanet, and had local hosts in 52 cities by the early 1980s. Tapping into that network’s mail system allowed Bill and his hacker friends to make local calls to chat, rather than tricking the phone system into letting them make long distance calls for free—a necessity if you wanted to post on a BBS outside your area code without amassing huge bills.

Someone told Bill that administrator accounts for GTE’s Telemail simply used a capital A for the password. “So I would just try last names with capital A and I would get a lot of accounts,” Bill tells me. “So that was what let me in to be able to make other people’s accounts, and we’d just have conversations.”

Bill’s plea agreement is thin, with just eight pages detailing his “crimes.” In 1983 there were no computer hacking laws, but the courts in Virginia clearly thought that penetration of computer networks was a serious crime, even if nothing was stolen. So Bill was charged with wire fraud, which essentially amounted to the crime of making three phone calls with his computer.

When we leave Starbucks and go to lunch, Bill packs up his tablet and charger and puts on his backpack. He throws his clear plastic bag, filled with blankets and a small tent, over his head, carrying the enormous parcel with the weight distributed on his pack and the back of his neck.

As we eat, Bill tells me stories of the past 30 years, of his struggles with mental illness and living on the streets of San Diego, Los Angeles, and Santa Barbara. We trade stories about the different psychiatric medications we’ve tried. I’ve been having issues with my depression and mood stabilizer meds, which make me incredibly tired throughout the day. Bill’s convinced that self-medication is the way to go. He shares that he’s been diagnosed as manic depressive and has had a few involuntary trips to the local mental health facility via police—the “taxi service,” as he calls them. Bill tells me that when it comes to basic hygiene, he showers at his brother’s place in town. I can’t bring myself to ask why he doesn’t live with his brother.

Throughout lunch I try asking in at least three different ways what Bill’s motivation for hacking was. Each time, it was like asking someone why they’d read a book or watch a movie. Bill says he just wanted to know what was out there. There’s a blunt cadence in his tone that makes me believe him, and the FBI documents bear this out. When he’d crack into financial institutions it was always shallow. He wasn’t looking to steal a million bucks or get deep into any system for personal gain. But he did enjoy being a voyeur. Bill and his friends would often pull pranks, like getting all the phone operators from a certain area on a giant conference call together. Chris even got a bunch of senior military personnel on what must have been the most confusing phone call of all time.

Despite having his home raided and computer equipment seized, Bill wouldn’t be charged for nine months. He says he didn’t want to get a lawyer and was confident that he could fight on his own. Bill tells me his strategy would’ve been to convince a jury or judge that his crime was like walking into a huge mansion, unlocked. He just wanted a look around. As Bill explains his thought process I hold my tongue, knowing that this line of reasoning makes sense to someone who grew up in a hippie family and the Western ethos of exploration that often comes with it. But I also knew that it wouldn’t have worked for a second in front of a federal judge on the other side of the country.

Bill’s father convinced him that he needed a lawyer; a move Bill still thinks was a mistake. They struck a deal, giving Bill three years probation for pleading guilty to three counts of wire fraud. Bill’s family moved to Alaska and Bill moved in with friends in Poway, California. Without a computer, he went dark on the BBS boards. He attended the University of California-San Diego for a while, but soon traveled to Mexico and then to Oregon. He never told his probation officer where he was going, and was picked up in Oregon and flown to San Diego, where he served 3 months in jail.

After getting out, Bill knew he had to find a way to make money. He weighed about 120 pounds at the time and needed income. Bill says he was “sort of fasting,” though his eyes betray that he probably didn’t have any money for food. Rather, he found his desire for a computer even more important than his hunger.

“I really wanted a computer but I couldn’t figure out how to make money to buy a computer,” Bill says. “When I first bought a computer [in 1980] I already had $500, but by this time I didn’t really have any money saved up or anything.”

So he cut out all the headlines he’d collected from friends across the country; splashy sensationalistic spreads about The Cracker’s big FBI bust. He found a literary agent, and wrote his entire book proposal by hand before hammering it out on an old typewriter. His agent got two responses, one from Microsoft, which offered a $5,500 advance. The book, co-authored by Howard Reinghold, was published in 1984 under the title Out of the Inner Circle. Bill immediately spent the entire sum of his advance on a new computer.

When his royalty checks started drying up around two years later, Bill looked for work here and there. He took a job with Scientology that promised $200 a week selling books, but quickly learned that he’d be making $1 a day and promptly quit. Today he’s able to feed himself, buy medicinal weed, and sometimes splurge on a tablet thanks to Social Security payments and California food stamps. But he hasn’t had a stable home since high school.

Bill’s entire existence is stuffed into three bags, and keeping an eye on them is a constant struggle. When his stuff is stolen, he often doesn’t know if it’s by other homeless people or the police. He says he has to buy new blankets once every three weeks. And his $150 Samsung tablet is always in danger of getting stolen.

Bill’s life, he says, is a constant stream of indignities and harassment from police. They enforce ordinances arbitrarily and inconsistently, trying to push homeless people out of sight. Bill tells me of a bridge he was sleeping under in Santa Barbara. An officer approached him, handcuffed him, searched all his belongings, and told him he couldn’t sleep on that side of the road under the bridge. He was cited for “illegal camping” but was told that sleeping on the other side was okay. So the next night he moved across the street. The police officer came back and gave him another ticket. Bill figures he has about $10,000 in unpaid legal fees and fines—most of it interest on the debt that grows and grows over time.

It couldn’t be further from the life of Chris, the 14-year-old who exchanged a brief phone call with Bill after his own FBI raid. Chris’s story is that of a kid who grew up to thrive in the culture of our burgeoning internet. With just a few minor tweaks, Bill’s story could have been similar. Bill tells me he hasn’t talked with Chris in 30 years, and they never met in person. But he has only fond memories of their friendship from halfway across the country.

I spoke with Chris over the phone under the condition that I not use his real name. In the early 1980s he was known online as the Wizard of Arpanet, a moody punk who bragged incessantly about the networks he’d penetrated. Today, he’s an upstanding family man “working with computers” (he declined to get specific) in a suburb of Detroit.

“It’s been a long time since I’ve talked about the Wizard of Arpanet days,” Chris tells me over the phone from his home outside Detroit. Chris was 14 when the FBI came knocking on his door.

Chris was an Atari guy, and his first computer was an Atari 2600. “You could plug in a basic cartridge and it had like 1k of memory and you could do some cool stuff with it. Then you kinda stepped up to the Atari 400, which was cool because you could do some programming but then you could get the modem—that 300 baud modem on there. Then you started to figure out what you could do with a 300k baud modem.”

Much like Bill, Chris found that his computer was a connection to the outside world; a sense of community that he couldn’t find elsewhere. “Growing up in Detroit there wasn’t a vast amount of things to do, so you had this modem and you start exploring,” Chris says. “You find your first bulletin board and then that bulletin board has a little bit of information on it and you kind of... that’s what intrigued me. In a general sense it hasn’t really revolutionized much from there—you called in to the bulletin board, you post messages, and you call in back and forth. It was a lot slower and there were no graphics, but the essential kind of concept was the same [as today].”

The key to hacking in the early 1980s was figuring out how to make free phone calls. Phone phreakers had been doing this since the 1960s, but it was even more vital for precursors to our modern internet. Dialing into a BBS in your area code wouldn’t cost too much. But if you were in Detroit and wanted to access a board outside your area code, that meant long distance calls. And long distance calls used to be damn expensive. So any computer hacker worth his salt quickly learned how to “hack” the phone company—and that’s what the Wizard of Arpanet started doing.

“That opens up the world,” Chris tells me. “Now I can call a BBS in New York or I can call this board over here in San Diego. And then you start getting out there.”

And once you were “out there,” the hackers of The Inner Circle and elsewhere would have a variety of ways to break into networks. Except that during this period, security was so weak that “break” is too strong a word. An operating manual could yield active administrator passwords for a variety of systems simply because nobody bothered to change the default passwords.

Chris’s true love, though he’s reluctant to talk about it today, was hacking the Arpanet and military systems. In fact, that’s how I found him. I was researching what kind of espionage the Soviet Union was conducting on the Arpanet and Milnet in the 1980s. We know of a few Soviet hackers who were looking for state secrets, but there were also kids like Chris rummaging around MIT, Stanford, and UCLA for fun.

“Then we started to get some of the Arpanet stuff, and somehow I got one of the main dial-in connection points,” Chris tells me. “And from there it was just kind of discovering all the different hosts.”

“Once you were able to get into one, I was able to get the full host list. So I got the full list of hosts on the Arpanet just from snooping around. From that point I was able to go through and just test them all out,” Chris says. What he had tapped into was known as a TIP, sort of like a super-modem that routed information along the Arpanet. According to the FBI documents I obtained, the military and researchers at the various nodes on the Arpanet had not detected the penetration. Their informant, the BBS narc John Maxfield, was the one who learned about it straight from the Wizard of Arpanet’s mouth.

Chris had no idea that he was constantly being watched by one of his own. Maxfield, who went by the handle Cable Pair on BBS boards, was never approached by the FBI about the activities he was observing in the early 1980s. Instead, Maxfield approached them. He’d later recall walking into the FBI to tell them about the kids swapping software on BBS boards. The FBI replied that this sounded like a bad thing, but got tripped up when he started using words like “modem.” They had no idea what he was talking about.

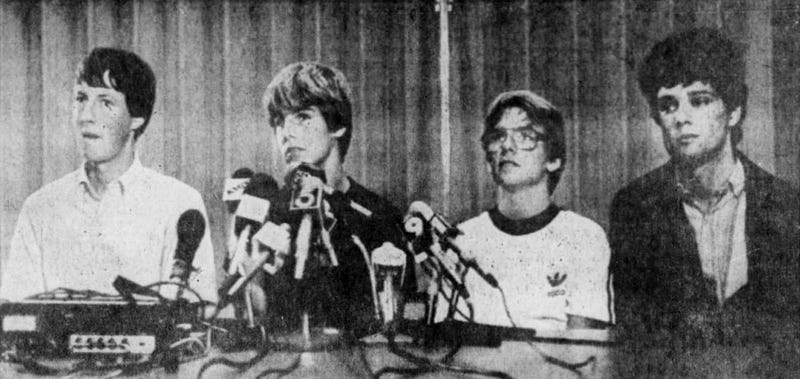

But after Maxfield’s initial contact, he developed a long term relationship with the agency. He set up meetings with hackers to gather evidence firsthand, and once allowed the FBI to photograph the kids from across the street in a massive sting operation.

“He invited a bunch of the different hackers from around the country to visit [him in Detroit]. So we all got together—it was like a hacker jam session—at the guy’s offices with all this phone equipment and computers,” Chris says. High school and college kids came from around the country. “It was like… ‘let me show you what I can can do,’ and ‘let me show you this.’”

Maxfield would say later that he was particularly impressed by the Wizard of Arpanet’s skills. Chris had no idea that he was incriminating himself with every keystroke. “The FBI took pictures of everybody that came and went, and they also had some early sort of keyboard monitors back then to see what was going on,” Chris says. “I happened to show them, ‘hey here’s the whole host list for the Arpanet! Take a look at this! This is pretty cool, I can get on any of these computers!’”

Maxfield rarely talked to the press after the raids, but journalist Patricia Franklin spoke to him for her 1990 book Profits of Deceit: Dispatches From the Front Lines of Fraud. When I contacted Franklin recently, she wasn’t surprised that Maxfield was hard to track down. He was secretive and self-righteous, she said, and used the same rhetoric that has become common in the 21st century whenever people talk about hacking or copyright infringement.

“Hacking is a completely impersonal, dehumanized crime,” Maxfield told her. “None of them would dream of taking a knife or a gun and mugging someone on the street. The hacker doesn’t know his victim and the victim never knows the hacker. There is never any physical risk involved. They are introverted thrill seekers.”

That tone would ooze out of the heavyweights at the FBI and elsewhere when it came to software and movie piracy. “You wouldn’t steal a... fill in the blank” is now little more than a punchline in online circles. But at the time, it was the best way to make the case that intellectual property should be considered real property and that virtual locks should be considered real locks. Maxfield literally compared himself to the Lone Ranger.

“With a computer, hackers can carry out their wildest fantasies,” Maxfield said in the late 1980s according to Franklin’s book. “And there is no one supervising them. It’s the alternative to a street gang. The hacker is a street-corner hood, except today the meeting place is a bulletin board.”

Maxfield became so infamous that the first issue of the legendary 2600 magazine, in January of 1984, dedicated its cover to the October 1983 raids and the outing of Maxfield as an FBI informant.

When Chris was finally busted, the FBI turned his bedroom upside down and took all his computer equipment. But Chris’s mother, who was home at the time, later defended him in an Associated Press article. “He bragged he knew how to do it, but he said he would never harm anything if he got in,” she said in 1983. “He would just look and leave. It was just the thrill of getting in.”

The FBI had two problems. One was that they were losing the public relations battle in the press. There are extensive notes in the FBI file about the fact that they’d have to tread lightly, since they were dealing with so many juveniles. The second problem was that there weren’t really any computer hacking laws. “Breaking into” a computer system wasn’t illegal, unless you took a broad interpretation of wire fraud law, as the FBI did with Bill. But since Chris was just 14, they struggled with whether to charge him.

The LA Times ran stories with headlines like “FBI Won’t Go Lightly on Whiz Kids,” but ultimately the agency did go easy on group members who were under 18. It was a calculated move, and one that would pay off, since so many Americans had no idea what hacking was. The idea that the FBI was picking on innocent, curious kids gained traction in communities like Irvine, California, where four of the hackers had their computers confiscated.

The local Irvine newspapers questioned heavy-handed FBI tactics, as kids held press conferences insisting that they didn’t do anything wrong. In fact, they pointed their fingers at Bill Landreth, The Cracker, for getting them involved. Bill’s physical isolation from the other hackers—like the four who knew each other in Irvine (two were brothers)—made him a mysterious figure in the press. Unlike the kids from higher income families, Bill had avoided the attention of newspapers.

The FBI never charged Chris with anything. He went back to school and relished in his new celebrity. “I got a lot of newspaper clippings, and then I became very popular and then I got a lot of girlfriends, and it was all good,” Chris says, laughing.

By the end of October 1983, the same month as the raids, the FBI was asking Congress for stronger anti-hacking laws. Or, rather, hacking laws at all. But to do that, the agency acknowledged that they’d have to redefine the legal meanings of both “property” and “trespassing.”

“Right now there is a void in the law,” FBI Deputy Assistant Director Floyd Clarke testified. “Our experience indicates that certain legal issues involving computer-related crime could be clarified, particularly the definition of property in the sense of a computer program having its own clearly defined inherent value, and the issue of trespass.”

The FBI would get their laws—and the teen cowboys of the Wild West would simply continue chasing sunsets. The first computer hacking law, the Counterfeit Access Device and Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (US Public Law 98-473, 1984), was enacted in 1984. But the laws would only grasp at the low-hanging fruit. Richard C. Hollinger’s 1990 paper “Hackers: Computer Heroes or Electronic Highwaymen?” argued that the laws only addressed the least disruptive elements in hacker society:

Currently we are in the midst of a paradox. The computer criminals doing the least harm and who are generally the least involved in malicious activities, “hackers,” have become almost the exclusive prosecutorial focus of computer crime law enforcement.

Bill and Chris were in the “least harm” category; they hadn’t stolen anything but time, if that can be considered a crime. The true computer thieves were those inside a given organization. A 1984 study by the American Bar Association, cited by Hollinger, found that 77 percent of computer crime was committed by a company’s own employees.

Essentially every computer hacking law passed since 1984 is a cousin of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. And the original Act itself is still being used (sometimes ham-handedly) by law enforcement today. It’s the law that internet activist Aaron Swartz was charged under after he downloaded a massive cache of academic papers. Swartz faced fines of $1 million and 35 years in prison. He took his own life in January of 2013 before the case was heard.

When I went to Santa Monica to meet Bill, I was pretty sure I’d hear a story about how the FBI had ruined his life. But I left believing that it hadn’t. The world ruined Bill’s life—a world that couldn’t quite find a place for his particular talents, faults, and petty mistakes. While it’s a cliche, it’s hard not to think that perhaps Bill was ahead of his time in many ways. He was smart enough to see vulnerabilities no one else could in what would become the modern internet. Legislation was drafted because few people in law enforcement had even thought what The Inner Circle did was possible, and digital security is now more important than ever. People get six-figure salaries to find vulnerabilities in networks today. But being just four years older than Chris meant Bill was tried as an adult and saw his life set on another course.

In Los Angeles it’s not uncommon to walk by familiar faces, briefly famous but now forgotten. Nobody does a double take when they see Bill. Instead, given that he’s one of the roughly 40,000 people sleeping on LA’s streets on any given night, people tend to avert their eyes from his gaze.

I thank Bill for sharing his story with me, and I leave him in Santa Monica. The world seems content to punish him for the victimless crimes he committed over three decades ago. But that’s certainly not unique to Bill or computer hackers. Who knows how his life would’ve turned out if he’d been embraced by the FBI, rather than prosecuted?

I asked Bill what was in his future. He says he’s thinking about writing something—maybe a book or a screenplay. But mostly he just isn’t sure. “I’ll probably end up not getting that far along,” Bill tells me with a nervous chuckle before we part ways. “I’d like to buy a house. But I don’t know.”