Suburban dirtballs of the 1980s are a lost culture, worthy of academic study, that disappeared abruptly, leaving mysterious artifacts for future generations to work over. Think of them as, say, the ancient Mayans, only with mullets.

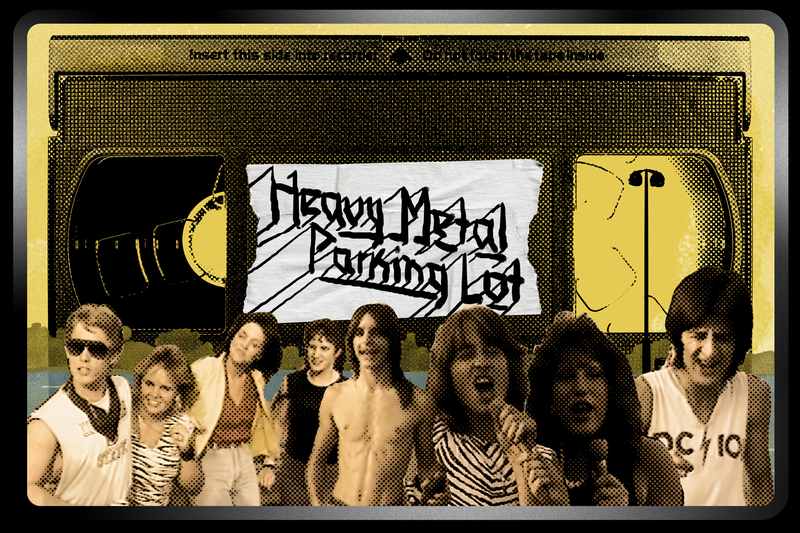

This, at least, is the judgment of the University of Maryland, where researchers recently scooped up the source materials for Heavy Metal Parking Lot, the 1986 documentary that captured metal’s underbelly as efficiently and shockingly as the Zapruder film caught the end of Camelot.

“The movie is a really fascinating primary source,” says Laura Schnitker, an ethnomusicologist and curator for the libraries at the University of Maryland, explaining the school’s push to procure the Heavy Metal Parking Lot papers. “You’re getting a firsthand look at a community, a subculture from a very musically specific time in history. The heavy metal years were quite something in the history of popular music, and the movie offers you a glimpse of this really distinctive, fascinating and kind of repelling working class culture that shares a love of a certain kind of music.”

“‘Repelling’?” asks the journalist.

“That means repulsive,” says the social scientist.

Oh, right. In that case, Heavy Metal Parking Lot, 30 years after it was made, remains repelling as all get out—in the most charming, hilarious, and fascinating ways possible.

The 15-minute movie was drawn entirely from footage shot by budding filmmakers Jeff Krulik and John Heyn in the parking lot of the Capital Centre in what is now Landover, Md., as Judas Priest fans pre-gamed for a show. It has no plot; no beginning, middle, or end; and, other than during the opening scene and closing credits, no Judas Priest.

Neither does it have any worries.

“That thing is the Citizen Kane of wasted teenage metalness,” says Rick Ballard, who makes a brief appearance as part of a gang yelling curses at the moviemakers. Like most of the Heavy Metal Parking Lot cast, Ballard only found out he was in the movie long after he’d grown up—in his case, to be boss of his own record label.

Krulik and Heyn never had any distribution network or marketing plan for the project, yet it nevertheless became an underground sensation through word-of-mouth. By the mid-1990s, you were as likely to find a VHS copy of Heavy Metal Parking Lot on a touring rock band’s bus as you were the King James Bible in a motel room. This singular document of metal’s heyday got talked up by, among others, Nirvana, the very combo credited (or blamed) for killing that era by ushering in grunge, and whose members’ stamp of approval gave HMPL the sort of credibility in certain rock circles that Pope Francis’s endorsement gave Mother Teresa’s sainthood campaign.

All these years later, it’s possible to rebuild the chain of custody and show exactly how a tape made it from Krulik to Kurt Cobain. Its standing as a viral video years before there was such a thing as viral video was the focus when the moviemakers hosted a panel discussion at SXSW in Austin earlier this month, and its seminal virality is among the things that made HMPL attractive to the academic types at the University of Maryland.

But it’s mostly about the fans.

“What we have now is this incredible body of anthropological studies that also happens to be extremely entertaining and very funny,” says Jim Healy, who runs the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematique program, dedicated to connoisseurs of obscure movies. “If you want to see how a certain demographic looked and behaved in 1986, watch Heavy Metal Parking Lot.”

While on safari through that concrete jungle outside the Capital Centre, Krulik and Heyn found a cast of real-world misfits united by their love of metal and the garb and highs that went with it.

“We knew people like this existed,” says Heyn. “But we’d never seen them all in one place, with everybody behaving a particular way and wearing a 3/4 tee-shirt and rocking a mullet.”

There’s the cherub who just after announcing herself as 13 years old is shown making out with a self-described 20-year-old Air Force enlistee who’d bragged he was “Ready to rock!” while holding a can of Budweiser in one hand and the poor, underaged lass in the other. And the shirtless, 17-year-old central casting stoner who introduces himself as, “Graham, as in gram of dope!” At a time when much of the nation was embracing President Reagan’s “Just Say No!” puritanism, Graham of Dope tells the camera that drugs should be legalized. A drug buddy standing beside him agrees, while making the brilliant period-piece observation that for all the laws against dope, the parking lot on this day held “enough burnouts to go Hands Across America.”

And the barefoot girl in a long white dress who qualifies as the belle of this dirtball ball, bragging in front of her high school pals that a boo-boo on her knee came from sex in the parking lot: “Don’t ever get it in a car!” she says, then yells out “Metallica!” (Deadspin caught up with the dressed-up delinquent—now known as Cherie Steinbacher of Springfield, Va.—to ask if that scream indicated she thought she was at a Metallica show; yes, she thought she was at a Metallica show.)

The consensus MVP of HMPL, however, was the kid in the zebra-striped jumpsuit so eager to spew bile against non-metal acts of the day (“Madonna … she’s a dick!” and “I don’t really give a shit about that kind of punk fuck!”) that he slams himself in the mouth with a microphone while spewing. Hence the birth of the underground rock legend known as … Zebraman!

“I always wondered if Zebraman has any idea that he was famous,” says former Nirvana roadie Mike Dalke, one of many rock and roll lifers who can recite lines from the movie the way David Koresh could quote Revelation. “Does he understand that he’s this epic superstar to so many people in rock and roll, that he’s the Olympic decathlon champ of teenage idiots, that he’s Zebraman, a legitimate superhero?”

We tracked down Zebraman, too—he’s a plumber outside Baltimore now—and asked those very questions. Spoiler alert to this Deadspin exclusive: Yeah, he kinda knows.

At the time the movie was made, those outside the metal realm could be both entertained and appalled that Graham of Dope, Zebraman and all HMPL’s other zonked-out characters really existed. Three decades later, even the folks in the movie have trouble believing this was really the way they were.

“Before Beavis and Butthead,” says Graham of Dope, “we were Beavis and Butthead.”

“It was just random, good luck that it was Judas Priest.”

Neither Jeff Krulik nor John Heyn has ever met Judas Priest. Not once. Not a single member.

“We’ve never heard from their lawyers either,” says Krulik. “So we’re okay with that.”

At the time they made the movie that forever linked him and Heyn to Judas Priest, Krulik worked for MetroVision, the cable provider for Prince George’s County, Md. He started there in 1983 as a door-to-door salesman. “I signed up Len Bias’s family to cable,” Krulik says. But by 1986 he’d worked his way up to manager of Channel 6A, the county’s access channel. The job put professional video cameras and sound recording gear at his disposal.

Heyn had studied film at Northwestern University, but was spending his days making VHS copies of industrial movies at Ari-Gem, a videotape duplication facility in D.C. He called Krulik and asked to work together after a story in the Washington Post mentioned Krulik’s plan to shoot a documentary about old movie palaces. Their first joint project was Forestville Rocks, a real-world Wayne’s World-style music show taped in the access channel’s studio featuring local freak-rockers Butch Willis and the Rocks.

They wanted to stick with rock and roll for their second outing. Heyn suggested they show up before a concert and just work with whatever they find in the parking lot. They had no particular band in mind, Krulik says, but Judas Priest’s Turbo tour was coming up at the Capital Centre. Krulik and Heyn weren’t Priest or metal fans—their musical tastes leaned more to new wave—but they’d seen enough kids with mullets and black t-shirts at the mall to surmise that the band would attract an interesting demographic.

“John had the idea, and I had the equipment,” Krulik says. “It could have been any concert. It was just random, good luck that it was Judas Priest. They were the perfect band, clearly an iconic metal band, that to this day really defines that era and that genre. But again, that was just luck.”

America’s relationship with metal, and metal fans’ passion for Judas Priest, were in flux when HMPL was shot.

The mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap had come out in 1984, but posted only middling box office numbers. Lots of grownups weren’t in on the joke, and still thought of metal as the devil’s music.

Events that helped put Priest at the forefront of metal, and ultimately helped give their rock doc long legs, were happening around the time of the band’s appearance in Landover. In the summer of 1985, the band came under attack from the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), the anti-rock coffee klatsch of Washington wives led by future Second Lady Tipper Gore. PMRC put “Eat Me Alive,” a song from Priest’s 1984 LP, Defenders of the Faith, on its roster of most offensive tunes, dubbed the Filthy Fifteen at the time. Gore told a scared nation that the lyrics described forced oral sex at gunpoint. She may have been right, but all she did was play to Priest’s base. (To tweak Tipper, the band put a tune called “Parental Guidance” on the follow-up LP, Turbo, the record Priest was promoting when their 1986 tour hit the D.C. area.)

A less giggly episode which also brought Priest national attention and heightened the band’s fearsome aura (and the metalheads’ ardor) happened in December of 1985. Just a matter of months before Krulik and Heyn descended on the Capital Centre parking lot, two obsessive fans of the band in Reno, Nev., shot themselves in the head in the parking lot of a church. The families of the suicide victims—18-year-old Raymond Belknap and James Vance, 20—sued the band, claiming the kids were driven to act because of subliminal messages they claimed the band was sending out through its recordings. The complaint alleged that backmasked recordings of the phrases “Try suicide!” ‘’Let’s be dead!’’ and ‘’Do it!” were planted on the 1978 Priest LP Stained Class. Judge Jerry Carr Whitehead, the federal magistrate hearing the non-jury civil case, initially and bizarrely ruled that language deemed subliminal wasn’t protected by the First Amendment. Bill Curbishley, Priest’s manager, denied any secret messages were on that album or any others. If Priest were to play the mind games they were accused of, “I’d be saying, ‘Buy seven copies!’” Curbishley said during the trial, “not telling a couple of screwed-up kids to kill themselves.”

Judge Carr ultimately dismissed the suit, but the affair immortalized the band’s dangerousness and guaranteed several generations of adolescents would flock to its music like moths to a flame—among them the soon-to-be-immortal teens who congregated in Landover, Md.

“We’re from MTV!”

Heyn and Krulik didn’t hold any lengthy pre-production meetings or storyboarding sessions in the days leading up to the concert. There was no strategy at all other than to just show up and roll tape. The shoot started poorly.

The first few interviews were held up by their attempts to explain who they were and why they were taping.

“We had pretty strict time limitations, because of sunlight and show time,” says Heyn. “We’re carrying a big camera and a bigger tape deck with an umbilical cable connecting the camera and deck. We started off saying we’re from Channel 6A and that got no response or them telling us they weren’t interested.” They thought camera battery life would become an issue, too. Weighing most heavily on the moviemakers: Heyn and Krulik had scheduled a double-date for later that night to go see Jayne Mansfield and Little Richard’s pioneering 1956 rock feature film The Girl Can’t Help It at an art-house theater.

So they began lying to the kids.

“We started telling everybody, ‘We’re from MTV!’” Heyn recalls.

That’s when the magic started happening. Krulik says the whole movie came from four 20-minute ¾-inch video tapes in the U-matic format, at the time the industry standard for newsgathering. “The fourth tape wasn’t used up,” he says.

When the moviemakers brought their haul back to the cable company studio for a first viewing, they loved the raw footage. They whittled things down to a quarter-hour of greatest hits and started dreaming. They didn’t fantasize about earning a cult audience, or merely regional popularity. They were sure their work deserved a landing spot far beyond Channel 6A.

“I wasn’t going to wave it around my employers,” Krulik says, “and we had higher aims as burgeoning documentary filmmakers.” .

But after Heavy Metal Parking Lot debuted in late 1986 at D.C. Space, a cool kids’ hangout located in an otherwise nightlife-free section of downtown D.C., they had trouble actualizing their dream.

“Movie festivals back then only took film, all we had was videotape,” says Krulik.

Their promotion of the movie peaked in 1988, when they were invited to screen it at the Kennedy Center as the opening act for Hail Hail Rock and Roll, Taylor Hackford’s internationally acclaimed documentary on Chuck Berry. Otherwise, screenings at some record conventions in the region were about the best they could hope for.

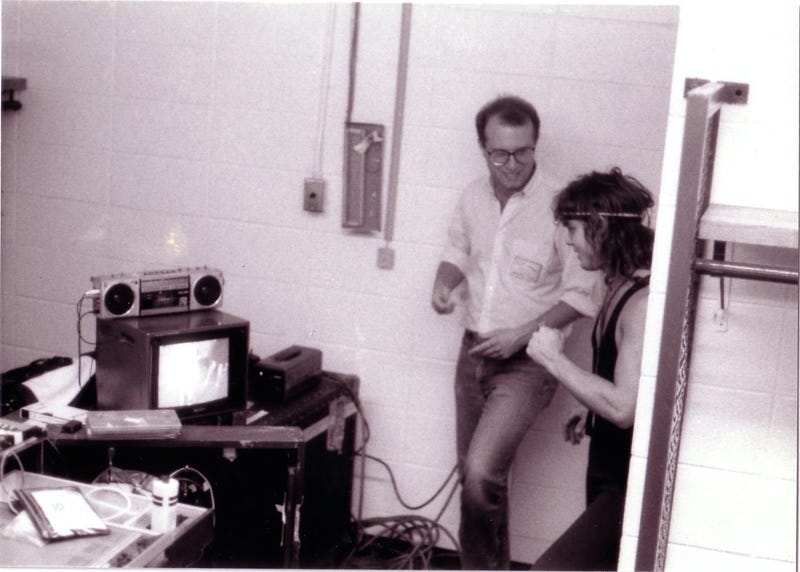

They hoped getting Judas Priest involved might spark something. When they heard the band was coming back to the Capital Centre for the “Ram It Down” tour in 1988, Heyn and Krulik convinced the promoter to give them backstage passes to hawk their movie. Back then, of course, screening at a remote location wasn’t as easy as breaking out an iPad or even a DVD player; they had to bring along their own professional equipment, including a bulky 3/4-inch tape playback deck and heavy monitor, plus a boom box to pipe out the audio signal.

Alas, all their hauling brought them was a night of rejection. They never got close enough to any band members to get any introductions. They did get near the catering tables, but were told to leave Judas Priest’s supper alone. The best they could do was get some of the band’s road staff to watch the movie in their dressing room. But even that went badly.

“They showed complete disinterest,” says Krulik, “other than the merch guy kept pointing out people in the parking lot and saying, ‘That’s a bootleg shirt! That’s a bootleg shirt!’”

They did get an apathetic Judas Priest staffer to give them the okay to show Heavy Metal Parking Lot over the Capital Centre’s video system, called the Telscreen, which hung from the rafters and was hailed as the first in-house replay system in the country. But they were told the movie had to be played very early in the evening—before the opening act, Cinderella, hit the stage—so as not to confuse fans into thinking that this was a band production.

A Capital Centre producer, though, nixed any screening. “He told us that [Capital Centre and Washington Bullets owner] Abe Pollin might be in the building, and Mr. Pollin wouldn’t approve of what went on in his parking lot,” says Krulik.

Krulik and Heyn slowly began giving up any hope that their movie would ever transcend the Beltway. Heyn got married and settled into a job working for the United Way. Krulik took a job with the Discovery network as a program evaluator, then was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease. A 1991 story about Krulik’s battle with the cancer in the Washington Post referenced several film projects he’d worked on to that point. The story contained absolutely no mention of Heavy Metal Parking Lot.

“Me and John were done with the movie, over it,” says Krulik.

But then fans of Heavy Metal Parking Lot took its fate into their own hands.

From Krulik to Cobain

Mike Dalke played perhaps the coolest role in the legacy of Heavy Metal Parking Lot.

“I’m the guy who got a tape of Heavy Metal Parking Lot on the Nirvana tour bus,” Dalke says.

Yes, Dalke was a key link in the chain of custody of the VHS tape watched by what at the time was the buzziest, if not the biggest, band in the world. Though the internet wouldn’t be close to mainstream for years after the documentary was shot and YouTube was about two decades away, the Heavy Metal Parking Lot video could be deemed literally viral: All the files were analog, and all the transfers were done either in person or through the U.S. mail, so germs from everybody in the chain might actually be found on the VHS tapes.

The chain starts in January 1992 at the offices of the Discovery Channel in Silver Spring, Md. Krulik took a call from Mike Heath, who he knew as a fellow University of Maryland grad and from reading local punk rock fanzines that Heath wrote for and edited. Heath had seen Krulik and Heyn’s work at a record convention in Silver Spring several years earlier, and never forgot it. He’d decided to move to San Francisco to launch a poetry career, and wanted a keepsake from his hometown to spread around. He asked Krulik if he could take some copies of HMPL with him.

“I knew what Jeff had done was great, and I didn’t want it to stay just a local phenomenon,” says Heath, who is still living in San Francisco and is an oft-published poet. “I knew anybody who saw it, even if you hated metal, would appreciate it. I knew it needed to get it out to the world.”

Krulik appreciated Heath’s kind words about the movie, and, even though he and Heyn had at that point given up their dreams about bringing it to the masses, he put together a care package of what he recalls as “about a half-dozen” VHS tapes of Heavy Metal Parking Lot.

Heath showed up at Discovery, and picked up the bounty.

“Mike Heath became the Johnny Appleseed of Heavy Metal Parking Lot,” says Krulik.

Once out West, Heath hooked up with Bill Bartell, who had a massive presence on the Southern California rock scene while using the nom de punk Pat Fear (his stage name was a tribute to Pat Smear of the Germs). Bartell played bass with the band White Flag and was a producer of lots of the region’s coolest bands. Heath mailed Bartell one of the second-generation VHS copies of HMPL he’d gotten from Krulik.

“I knew he would appreciate it,” Heath says of Bartell. “He called me back a week after I sent it and he was raving about how great it was and how he was going to spread it around.”

At the time, Bartell (who died in September 2013) was working with Redd Kross, the L.A. punk band, on the album, Phaseshifter. Redd Kross’ members had parties dedicated to screening funky videos. Among those exposed to HMPL through that scene was Dalke, who grew up in Hawthorne, Calif., with future members of Redd Kross, and occasionally roadied for the band.

“I was at a party where everybody was sitting around watching crazy tapes,” says Dalke. “I loved it. I knew Bill was a guy who was a great agent for the craziest underground tapes. So I asked him to make me one.”

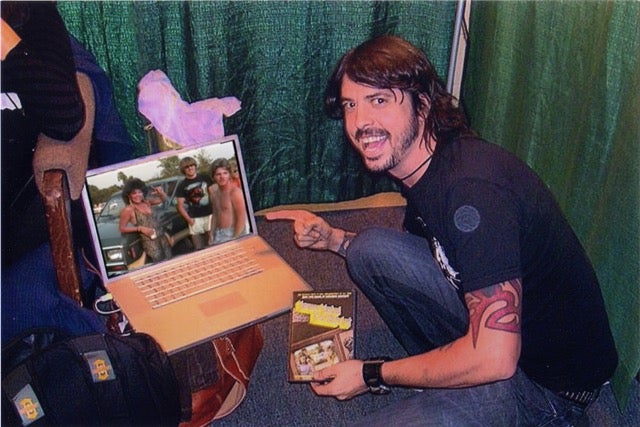

Bartell complied. Dalke then signed on with Nirvana for the In Utero tour in the fall of 1993 as a drum tech for Dave Grohl. All the cool touring rock bands of that era, Dalke says, had an unspoken competition to acquire the rarest videos to watch on the bus while on the road, the more bizarre the better. In the days before Netflix, rockers traded VHS tapes the way kids later would Pokemon cards. Before hitting the road for Nirvana, Dalke packed a copy of Heavy Metal Parking Lot.

The crew traveled on different buses than the talent; Dalke says he heard that somebody in the band bus had a tape of Toy Porno, a now-legendary video made by Milwaukee crass rockers The Frogs that has to be seen to be believed. So he proposed a Toy Porno/Heavy Metal Parking Lot swap to Grohl.

“The tape I had was handed to me directly from Bill Bartell,” Dalke says. “We made the trade.”

To recap the road to Nirvana: Krulik-Heath-Fear-Dalke-Grohl.

Cobain died in 1994, and Krulik is unaware of any interviews where he mentions the film. But Dalke vouches for the Nirvana frontman’s love.

“Everybody was blown away by the tape,” says Dalke. “I was high school class of 1985, same as Kurt, and Dave was a couple years behind, so when we saw that video it looked like all the Iron Maiden or Judas Priest fans from any high school anywhere. The way they talked, the way they looked, it was like all the kids we went to school with.” (For the In Utero tour, incidentally, Nirvana was using Pat Smear as second guitarist for live shows. So Pat Smear, now a member of the Foo Fighters alongside Grohl, in all likelihood watched Pat Fear’s copy of Heavy Metal Parking Lot.)

Through a publicist, Grohl declined to be interviewed for this story, but he has been among the movie’s longest-running and most spirited advocates. He described the documentary as “basically Rock and Roll 101” in a 2001 interview with the Los Angeles Times, and said he was still watching it frequently. When Grohl’s post-Nirvana band, the Foo Fighters, played Fairfax, Va., outside of D.C. in 2005, Grohl invited Krulik and Heyn backstage and took in a screening of Heavy Metal Parking Lot. Krulik remembers that backstage experience much more fondly than he does the one with Judas Priest in 1988.

Heath’s boots-on-the-ground promotion of HMPL on the West Coast is also believed to be responsible for getting the tape into the hands of Robert “Col. Rob” Schaffner, one of the most influential weirdos in Southern California, an outsider-film lifer who’d been mentored from age 13 on by legendary avant garde pornographer Russ Meyer.

Col. Rob was the proprietor of Mondo Video a Go Go, a movie rental store in Silver Lake that catered to outsiders. “I wanted something that was the total opposite of Blockbuster,” says Col. Rob of his store.

The store became known as the place to go go for “the impossible finds” of the movie world, as well as for offering “Fourth of July transvestite barbecues and greasepaint-coated re-enactments of the Easter story” back when those were good ways to fly the outsider flag.

Schaffner says he remembers getting his first copy of HMPL on a movie set where he was working on the crew. “A kid who knew about [Mondo Video] came up to me and handed me a tape and says, ‘You’re going to love this!’” says Schaffner. “It was a very bad, very grainy-ass copy, but very much enjoyable.”

Schaffner became HMPL’s most aggressive publicist. Years before he’d had any contact with Heyn or Krulik, Schaffner designed packaging for the movie and pushed it on his clientele like he’d done for few films. And that clientele included not only obscure cool kids, like those in the Redd Kross and White Pig punk circles, but also celebrities who toiled in the mainstream movie world. Col. Rob says Leonardo DiCaprio, Belinda Carlisle, and Nicolas Cage and his cousin, Sofia Coppola, were among those he introduced HMPL to. Schaffner says Coppola once came in and requested a batch of “like 10 copies” of the movie to give out as gifts.

Heyn and Krulik only learned about Schaffner’s promotion of their movie when Coppola phoned Heyn in 1994 and asked, one artist to another, for permission to use footage in a show she briefly produced for Comedy Central called Hi Octane. Heyn gave Coppola his blessing, though her show got canceled just three episodes in and before the HMPL chapter ran. But Heyn and Krulik established a relationship with Schaffner. Kudos were the currency Heyn and Krulik accepted in lieu of financial payment, so they ate up Col. Rob’s tales of how big the movie was among the weirdos out West.

Schaffner closed Mondo Video a Go Go in 2007, But the legacy of his advocacy of the movie to Southern California cognoscenti lingered on. In 2010, for example, choreographer Ryan Heffington conceived and produced Heavy Metal Parking Lot: The Musical for the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art.

And Schaffner is still pushing the movie. Col. Rob says that he did some visual arts work for the current Black Sabbath world tour, which started in January in Omaha, Neb. When he turned in his artwork, Schaffner says, he threw in a DVD of HMPL, figuring the band would love everything about the movie and get a particular charge out of the scene where a young metalhead calls Ozzy Osbourne fat.

Krulik is certain that without Heath’s work, his movie would have none of the celebrity endorsers it’s accrued through the years. All in the name of art, says Heath.

“Jeff gave us a peek into a scene that not too many people ever had, and I’m proud of him for carving out this humble and noble niche for himself,” he says. “And I’m humbly proud of myself for getting it out to the world.”

13 Will Get You 20

David and Dawn are the Romeo and Juliet of Heavy Metal Parking Lot. Their kiss is its only kiss.

And, objectively speaking, that kiss is, to use Prof. Schnitker’s parlance, repelling.

“I’m David Helvey, I’m 20 years old,” the cocky guy in shades and a cut-off t-shirt says into the camera. “I’m ready to rock.”

“Dawn. I’m 13,” says the young girl serving as his arm candy.

Then as God, Krulik and Heyn, and a gaggle of dirtballs are their witnesses, David and Dawn make out.

Ewwwwwww.

But wait! Three decades after the fact, both halves of this May/December (January/December?) couple want to set the record straight. The Devil didn’t make ‘em do it; the filmmakers did.

“It’s not what it looks like!” says Dawn Vermillion, now 43 and living in Colorado. “We were egged on off camera. Like, ‘Give us a kiss!’ And so we did. Nothing else happened that day! Really!”

Helvey, who also brags in the movie that he’s “leaving for the Air Force in two-and-a-half weeks,” seconds Vermillion’s claim that the PDA was directed. “They were saying, ‘Why don’t you guys give us a kiss or something?’” says Helvey, now 50. “Dawn was just a friend, and her parents were friends with my parents, and she’s still a friend.”

Dawn was plenty old enough to know better by the time she learned that her kiss, directed or not, was in a movie. Vermillion got the news from a call from her father in 2003. He told her that Helvey, an old family friend, had just knocked on his door out of the blue and asked in serious tones if could have a private chat. “My dad told me they went to the kitchen and David said, ‘Sir, I kissed your daughter and it’s out there on video,’” Vermillion says.

Helvey now says that he was 37 years old when an old high school buddy broke the news that he’d seen him in a movie and showed him Heavy Metal Parking Lot for the first time. He was horrified. To that point, he’d never heard of the movie.

“I went directly to her parents house to talk to her dad,” he says.

Vermillion says her father, who died in 2005, got a chuckle out of Helvey’s confession. “I know people have been saying on message boards for a long time that ‘That guy should be put away!’ and ‘What a creep!’” she says. “But David is not a creep. David was a total gentleman! Really!”

She says her dad was laughing when he told her the tale. He searched for a copy of the movie and even sent his daughter souvenirs he found on the internet with the Heavy Metal Parking Lot logo.

‘Yes, it was a scandalous kiss,” she says. “If I was the parent of me, I’d have been mortified. But for me, it was great! I’m glad I got to be a part of the movie. Oh, that day was so fun!”

Helvey is a little more circumspect. “I try to live a life with no regrets,” he says. “But I wish there was some way to change that to something more, well, appropriate. I hope I’m not infamous.”

Blue Oyster Subcülture

Last year, Krulik pitched researchers at the University of Maryland on his idea of turning over his papers.

He had worked with Schnitker and the school’s curators for a 2013 exhibit on WMUC, the student-run radio station where he worked during his time as an undergrad there (Class of ‘’83). A lot of fellow former station employees had donated their tchotchke for the exhibit.

“The gears in my head turned,” Krulik says. “I knew Heavy Metal Parking Lot had this milestone coming up, I’m an alum, and they had a mission to do what I was always doing on my own: to save and preserve.”

He wrote up what curators call an “proposal for accession” in which he offered to turn over pretty much everything he’d accumulated during what he called a career spent “tapping into the rich ore of local culture in the Maryland/D.C. region.”

Schnitker loved the idea, and soon enough the school had dispatched a moving crew to the storage space in Gambrills, Md., that he’d rented for decades and hauled away some 200 linear feet of source materials from documentary and history projects he’s worked on.

Schnitker says Krulik’s stuff will be held in the university’s Hornbake Library in the section for special collections for mass media and culture. The goal is to have the materials catalogued and available to researchers by the end of the year. The stockpile also covers Krulik films such as Led Zeppelin Played Here, a movie that explores the legend of the band’s concert at a small recreation center in Wheaton, Md., just before becoming the gods of hard rock, and Hitler’s Hat, about an American World War II veteran who in the mid-1990s began showing off a top hat he’d claimed to have swiped from the Fuhrer’s Munich apartment half a century earlier. But Schnitker makes no bones about which part of the haul has excited her the most. “The highlight of the collection is Heavy Metal Parking Lot,” she says.

That portion of the collection includes all the extra footage, three decades of movie posters, newspaper and magazine clips, and television clips about the movie.

Schnitker says she is not a metal fan, and that everything she knew about rock concert crowd behaviors before diving into Heavy Metal Parking Lot came from going to a Kid Rock show in Detroit when the Devil Without a Cause tour stopped by. She had studied at the University of Michigan, and her friends there were going to make an event of the visit from Rock, who was something of a local hero. “I was not a fan,” she says. “I sound old if I say he was ‘vulgar,’ but I found him loud and obnoxious. But they were going and I didn’t want to miss out.”

How was it? “I remember a woman took off her shirt and then her bra. I always felt bad about that,” she says. “But I had fun.”

I ask what music she carries around with her on her phone—“Delta Saints, Django Django, Spoon, Pink Martinis,” she says. No Priest, though she calls the band “one of the more prominent and pioneering” metal acts of all time. And while the music doesn’t hold her attention, the movie sure does.

“What strikes me about the film is that it’s really nothing about [Judas Priest] at all,” she says. “This is a movie about the fans. It’s their story. It takes place in a parking lot, not a concert stage, and it does feel like you’re getting this in real time. The daylight never changes. And when it ends you’re not sure what you should think about it, and that’s where the art is in it. And it’s a great example of somebody going out and doing their thing and then distributing it, like DIY with punks. The fact that it made no money adds to its charm.”

Heyn says he’s thankful for the academic appreciation his documentary is suddenly getting, and that his movie deserves it.

“It’s kind of forgotten now, but, this was a common way to grow up as a teen in the ’80s,” he says. “I think we captured that era really well.”

Rick Ballard, who says he didn’t find out that he had a cameo in the movie until “around 1998,” also believes in the movie’s cultural significance. Along with being a documentary filmmaker of his own, Ballard is owner of Acetate Records in Los Angeles, where he moved in 1992.

“The movie shows a different world,” says Ballard, who grew up outside D.C. in Falls Church, Va. “You could buy beer at 18, so everybody could get beer. We had smoking courts in high school and my seventh grade field trip was to the Philip Morris factory. There I am, 15 years old, trying to grow my hair out, hanging out in the parking lot at Cap Centre drinking with a friend who was inappropriately older. I have no idea what my parents knew or why they let that happen! It was really the age of pre-awareness. There was no social media, no internet, no nothing. I see how my kids have grown up and they react to things immediately. Back then, you had to go out and meet people to do anything or get anything. I had to get on a train to New York to get the cool records I couldn’t get in D.C. I wear a shirt now, too, so that’s different.”

“I’m glad that movie exists,” he says, “and the fact that it exists at all is unbelievable to me.”

Stacey Payne, whose star turn came with her wasteoid scream of “Langley Park!” as Krulik’s camera rolled, can testify to the lack of awareness of at least one 1980's demographic: parents. Payne recalls getting third-row seats to the Judas Priest show by successfully sneaking out of her house the night before tickets went on sale to camp out at the box office. Payne, 15 years old at the time, was on the loose again the night of the concert.

“I told my mother I was ‘spending the night at Janine’s,’” says Payne. “I spent a lot of nights at Janine’s when I was 15. Janine didn’t exist.”

While the cataloguing of Krulik’s materials is taking place, Schnitker is planning a year-long exhibit at the school for Heavy Metal Parking Lot. That display will open with a party over Memorial Day weekend, which will include panels of film and metal historians ruminating on its meaning.

Jim Healy of the University of Wisconsin-Madison will be among the academics brought in for the event.

“What Heavy Metal Parking Lot does is very important,” says Healy, who will co-host a screening of the movie with Krulik. “It represents a kind of foreshadowing of what entertainment would become and has become. They were working with low-budget video equipment that was at their disposal, and turning their cameras on average people. That’s what everybody does now in the age of YouTube. These people are kind of all the same, and this music, this band, gives them a reason to come together and drink and do whatever.”

Krulik’s camera caught Zev “Z.Z.” Ludwick questioning Priest vocalist Rob Halford’s sexuality while wearing a Star of David necklace but no shirt. Ludwick says metal gave him a way to rebel against his family’s strict observance of Judaism. His brother at the time was a rabbi in Israel, while Zev played bass in a heavy metal band called Steel Winch. That music fetish didn’t play as well in the heavily Hasidic section of Silver Spring, Md., where he grew up as it did in the Capital Centre parking lot.

“Metal was a subculture at that time, and it was a way for misfits to fit, to feel like they were a part of something bigger,” says Ludwick.

Graham of Dope says the metal crowd embraced him at a time nobody else would. He says he’d dropped out of school and was living out of his car in the spring of 1986, having been kicked out of the housing at Andrews Air Force Base where he’d been staying with his sister. His metalhead clique, called the Party Lords, was his family. “Looking back, that’s all I had,” he says.

Cori Coates was, judging by the documentary, one of the few black kids in the parking lot that day. He shows up in the movie standing near his canary yellow 1979 Chevy Chevette hatchback, now accepted as one of the crappiest vehicles to ever roll off a Detroit assembly line. Coates says his first embrace of metal helped him fit in with the overwhelmingly white student body at his elementary school in rural-ish Edgewater, Md., and he’s never given it up. “I quit my job as a cook just to see Judas Priest,” he says. “I was supposed to work that night, and it came down to my job or that show, and I wasn’t going to miss it.”

This subculture had, obviously, a distinctive music. And a shared fashion sense, with the dominant male ensemble featuring both a black t-shirt with a metal band’s name on it and a mullet. The metal clique also had its symbols—the devil’s horns were flashed at the moviemakers throughout their parking lot foray. And, Schnitker points out, members had shared rituals, such as getting fucked up.

I asked several cast members what kind of things they put into their bodies in the arena parking lot. Turns out there was no consensus favorite among the intoxicants.

“I just drank beer,” says David “I’m Ready to Rock” Helvey.

“Weed,” Cori Coates says, “Lots of weed. Lots and lots of weed.”

“PCP,” says Graham of Dope. “For me and everybody I knew in the 1980s, it was PCP.”

“It’s a lock we were wandering the parking lot buying or selling LSD,” says Sam Varias, the guy who in the movie argued for drug legalization and suggested there were “enough burnouts to go Hands Across America.”

“If you remember that,” says Z.Z. Ludwick, “then you weren’t really there.”

By Ludwick’s standard, then, Tonya Godsey very likely was in the Capital Centre parking lot in May 1986. Because when I ask Godsey what her drug of choice was for the Priest tailgate, she stumbles trying to come up with an answer. She decides she needs to ask Cherie Steinbacher, the barefoot girl in the white dress with the boo-boo seen standing in front of Godsey in the movie. As luck would have it, 30 years later, they remain best friends, and Godsey and Steinbacher, both living in Northern Virginia, happen to be hanging out together on the day I call.

“What did we take that day?” Godsey asks.

“Everything,” responds Steinbacher. “I know I did a lot of acid.”

“Yeah, everything,” says Godsey, as if her bestie’s acid flashback gets the synapses firing again. “Acid, cocaine, beer. It was nothing to smoke pot all day, either.”

“Yeah. says Cherie.”More like: What didn’t we take?”

Crass Reunion

Krulik hopes to turn the Heavy Metal Parking Lot exhibit’s opening weekend into a cast reunion. He says he has genuine affection for the characters, and is eager to see how they all turned out.

But, among everybody who was in the parking lot that day, Krulik clearly has a favorite.

Zebraman.

To wit: When Krulik designed a simple label to put on the VHS tapes of his movie, Zebraman was the only character in the graphic. The poster that will be used in Maryland’s Heavy Metal Parking Lot exhibit also features Zebraman.

He’s not only the conscience of the movie, he’s its face, and its mullet, too.

He’s the dirtball wearing a sleeveless shirt and pants combo with matching zebra stripe, delivering a 42-second monologue that has over time has come to be recognized as the Gettysburg Address of metal:

“Heavy metal rules! All that punk shit sucks! It doesn’t belong in this world, it belongs on fuckin’ Mars man! What the hell is punk shit? And Madonna can go to hell as far as I’m concerned! She’s a dick! Seriously! [Hits self in mouth with microphone] Ow! Heavy metal definitely rules! Twisted Sister, Judas Priest, Dokken, Ozzy, Scorpions. They all rule! [Takes break from rant to acknowledge nearby stoner girl] Yeah, she’s tripping Jack Daniel’s. [Resumes rant] It all rules! All that shit rules! This punk shit, circle shit and the dicks and all, that can all go to hell! I don’t care, you know? I don’t really give a shit about that kind of punk fuck!”

Zebraman’s renown transcended the metal subculture. Kevin Fitzgerald, a drummer on the LA punk scene and avowed HMPL devotee, is convinced, and quite proud, that Zebraman was attempting to slam one of his former bands when he stammered through the, “This punk shit, circle shit” portion of his speech.

“I was sure he was trying to say ‘Circle Jerks!’ but can’t get it out,” says Fitzgerald, who drummed for the Circle Jerks (alongside former Redd Kross member Greg Hetson) for a decade beginning in 2001. “I saw that and was thinking, ‘Almost made it!’”

Krulik says he tried for years after the tapes went viral to figure out who Zebraman was, but had nothing other than the footage from 1986 to go on. He and Heyn were so mesmerized by the kid they never bothered to ask for his name. Then along came the internet. And in 2003, they found a post about Heavy Metal Parking Lot on a message board outing Zebraman as a guy named David Wine who went to Perry Hall High School.

They found him in Middle River, Md., north of Baltimore. Wine didn’t respond to phone messages, so they showed up at his house with a camera. But the meeting went about as well as their attempt to screen their movie for Judas Priest backstage at the Capital Centre (which was demolished in 2002). Wine said he didn’t know about the movie and had never heard of or been called Zebraman. He politely declined their invitation to reminisce about heavy metal, saying he was more into country music at the time.

Krulik admits being crushed by the whole encounter, particularly learning that Zebraman had undergone a country conversion. Krulik told me he wanted nothing more for the 30th anniversary of his movie than to have another chance to talk to Zebraman, but the 2003 contact information for Wine was obsolete.

Deadspin found him. Zebraman is now 46 years old, runs his own plumbing service in Baltimore County, and is a happy grandfather. And he’s back on the metal bandwagon.

“Metal meant, like, everything to me,” Zebraman, er, Wine tells me. “It was a place to go, it was friends, it was everything. We had the privilege of growing up in the greatest music era. For us and heavy metal, it was great.”

The first album he ever bought was Screaming for Vengeance by Judas Priest in seventh grade. “It was what the kids in school were talking about,” he says. “It was all, ‘Dude, you gotta check this out!’ And I did, and, wow, it was awesome. The guitar riffs, the lead solos. I was like, ‘Holy mama! How do i get into this?’”

Before long he was shopping at both record stores and clothing emporiums that catered to metalheads. The Zebraman costume debuted in the parking lot. But that wasn’t the last time he put it on. “I wore it to school a couple times, too,” he says, “and then for a KISS concert.” He doesn’t know what became of the costume that helped make him a cult legend; only that he doesn’t have it anymore.

He kept going to metal shows in the years after the Priest show in Landover. He was a regular at Hammerjacks, the coolest heavy metal club in the Mid-Atlantic states before it was demolished to make room for Ravens Stadium. “I saw Slayer at Hammerjacks,” says Zebraman. “It doesn’t get any better than that.” (He’s right. Slayer at Hammerjack’s is the metal equivalent of seeing the Beatles at the Cavern Club.)

Word of Zebraman’s legendary stature reached Wine’s family and friends over the last decade, to the point where there are few large gatherings where somebody doesn’t blurt out some portion of his epic rant back at him. So, to answer the question of whether Zebraman knows that he’s “the Olympic Decathlon champ of teenage idiots” to generations of the movie’s fans: He’s got a pretty good idea of that.

“‘Madonna, she’s a dick!’ I hear that repeated a whole lot,” says Zebraman. “I don’t know why I disliked her so much, but, those videos of hers were ridiculous. It wasn’t personal, Madonna!”

And his slamming “that punk shit”? “It was always tense between punks and heavy metal kids at school,” he says. “They called us ‘maggots’ and ‘grits,’ so all the tension came out in the movie. It wasn’t the music. If we’d have gone to shows together, we probably would have had some fun.”

The last rock show he attended was Metallica in the early 1990s. Zebraman still listens to metal, but more Iron Maiden than Priest. He’s looking forward to the day when the grandchild is old enough to go metal concerts. “That would be an excuse for me to have to go, too,” says Zebraman.

Neither Wine nor Zebraman have told Krulik if they can make the reunion. A few alumni have RSVP’d in the affirmative. Graham of Dope will be there. He says he never got his high school diploma, that through the years he was briefly locked up for drugs, and that he once ran away with a traveling carnival, but has lived basically a straight-edge life for a good while. He now goes by Jalyn Graham Owens, and is an executive chef in Ocean City, Md. He’s self-publishing a memoir. He’s now got four kids and two grandchildren. He says he no longer rocks: all the buttons on his car radio are programmed for “NPR, sports channels and talk radio,” and the last concert he attended was Dave Matthews at Hershey Park near the turn of the century. “I left after like three songs,” he says. His offspring know all about Heavy Metal Parking Lot, and love him all the more for his part in it.

“My teenage daughters have a ringtone of me saying that stupid shit,” he says. “They think I’m a badass rocker.”

Z.Z. Ludwick will likely show up, too. He’s become close to Krulik in recent years, and remains a fan of the movie despite his wholesale rejection of the music and lifestyle of his youth. Ludwick runs an acoustic instruments repair and retail shop, Ludwick’s House of Violin in Silver Spring, Md. He plays mandolin and listens mainly to Hasidic music. He does no drugs. He has two girls, ages 12 and 13, and they don’t know about Heavy Metal Parking Lot. He doesn’t let them listen to heavy metal.

“Heavy metal comes from a dark place, and I have no place for that in my life,” he says. “My girls are into One Direction and, what’s her name?”

“Taylor Swift?” I offer.

“Yes,” he says. “One Direction and Taylor Swift.”

Stacey “Langley Park!” Payne will be there. The blotto 15-year-old delinquent is now 45, and works in Baltimore as a financial fraud investigator. “And I’ve got security clearance,” she says. “I want to show up so people can see we didn’t all end up derelicts.”

Cori Coates, now a systems analyst and weekend DJ in the Baltimore area, also intends to be at the reunion to show that the kids are alright. He says that a house fire on Easter 2015 destroyed his entire album collection. “All my Priest records burned up.” He says he thinks about the guy he was in May 1986 all the time. “He was much more fun-loving than I am,” Coates says of his teenage self. “He didn’t really give a fuck about anything. Live for today. But he turned out okay.”

David and Dawn both say it’s going to be tough to make the reunion, but that the hearts are willing. Dawn Vermillion now lives in Colorado and is an artist. She says family obligations could keep her away. She’s been taking her now-teenage son to concerts his entire life—she drove for hours to catch a Bob Dylan show with him as a tot—and says going to concerts is still “her church.”

David Helvey says he never made it into the Air Force like the guy in Heavy Metal Parking Lot was planning, but declines to say why other than, “It didn’t happen.” Now 50, he says he’s been living out of his car in California since last year, driving up and down the coast from San Diego to the Oregon line and back as a driver for an unnamed ride-share company. He stops in beach towns to draw and has just posted lots of his artworks online. “I realized a while ago you are the music you listen to,” he says. He says he couldn’t afford to carry a guitar with him, but the inspiration of his art is now “the music in my head.” He’s listening to Bob Marley a lot lately. He has fond memories of the bygone days when he was ready to rock, and remains awed that some folks still find stuff he said and/or did in a parking lot 30 years later interesting.

“I mean, the guys in Nirvana probably know me on a more personal level than I know them,” he says. “How do you get your head around that?”

If Cherie Steinbacher and Tonya Godsey go to the reunion, it’ll be together, just like at that Priest show. “I really thought I was going to see Metallica,” says Steinbacher. “I was so wasted. That was one of the best days of my life.”

The lifelong friends, now 48, say they talk all the time about their good ol’ days, the gist of which is captured in Heavy Metal Parking Lot. Steinbacher says that as a mother she felt sad that her daughter grew up more concerned with getting good grades than with having as much fun as Mom had. Asked if she would change a thing about her own adolescence, Steinbacher says, “Oh, god no! Absolutely freaking not! I’m talking, I had the best time all the time. Me and my girlfriends rocked. I regret absolutely nothing!”

Godsey, who says she skipped her high school prom for that Priest show, seconds her pal’s emotion. “I wouldn’t do anything different either,” she says. “Maybe remember a little more. I mean, those were the best days. I’m glad that we have those memories, the ones we’ve got.”

Rock label business will keep Rick Ballard from making the trip east, but he says the movie commemoration should go on just fine without him.

“My contribution was only yelling ‘Fuck yeah!’” Ballard says. “And I stand by that to this day.”

Know something we should know? You can reach the reporter at dave.mckenna@deadspin.com. Top art by Jim Cooke.