Forty years ago, an incredibly powerful collection of horror movies filled American theaters, including The Omen and Carrie. But 1976 was also a time of political turmoil and a great deal of cultural unease. These seemingly disparate facts are likely far more connected that you realize.

In ’76, the country was dealing with more than just the aftermath of Watergate and the Vietnam War. It was also the time of the Cold War, the Space Race, the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, Son of Sam, the Sex Pistols, the Entebbe Raid, In Search Of..., and ABBA’s “Dancing Queen.” Current events and pop culture sometimes collided—as with Watergate tale All the President’s Men, or Helter Skelter, the TV miniseries that dramatized the Charles Manson case.

Likewise, horror movies—a genre well-known for sneaking social commentary into stories that, on the surface, appear to merely address monsters and madness—were also extremely popular that year, and audiences had an unusually high-quality assortment to choose from. So much so, in fact, that author and horror scholar Robin Wood famously dubbed the decade “the Golden Age of the American horror film.”

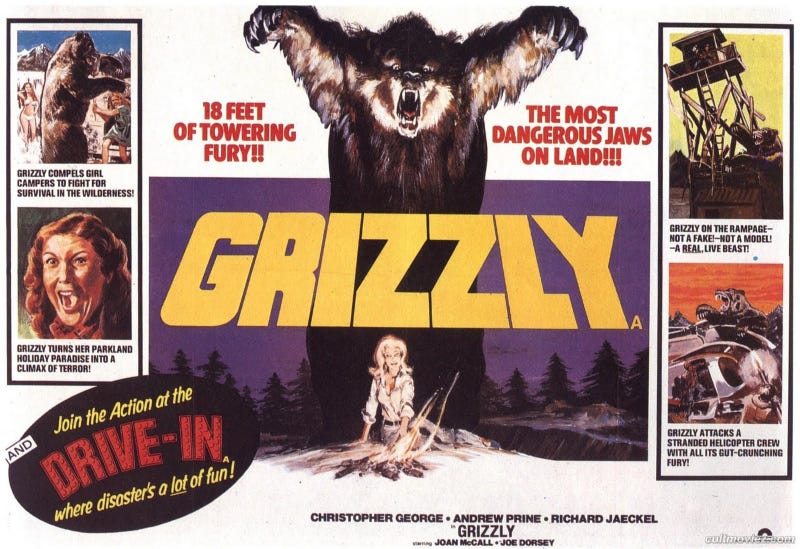

Just to get it out of the way, the influence of Jaws, the biggest moneymaker of 1975, cannot be overstated. Animal horror was huge in 1976, with films including: Grizzly (tagline: “The most dangerous jaws in the land!”); Ape (which was also conveniently timed for the King Kong remake); and the singularly bizarre The Food of the Gods, in which a mysterious substance infects a remote island’s vermin population, resulting in a plague of monster-sized rats.

Rampaging animals will always be a reliable source of entertainment, but a better time-capsule of the uncertainty of the mid-1970s is contained in staunch B-movie God Told Me To. It begins with a sniper in a tower (in a scene that features a brief appearance by comedian Andy Kaufman)—10 years after Charles Whitman terrorized Texas, but eight years before a deadly spree at a Southern California McDonald’s would signal the beginning of our still-ongoing mass-shooting epidemic. In Larry Cohen’s film, the title is the motive, and the NYPD officer who takes on the case traces that divine order back to a cult leader who is actually part alien. Then the cop finds out he’s part alien, too.

An extreme identity crisis—as well as some intense confusion about faith, religion, and the very nature of existence—ensues. God Told Me To is an extremely weird movie (Roger Ebert’s review kindly calls it “confused”), and an undeniable product of its times. In an interview with the UK’s Independent in 2013 about his career, Cohen said, “I want the picture to be about something—not just action and violence.” God Told Me To has since become a cult movie, partly because it’s full of WTF awesomeness, but also, as Rolling Stone writes, “There’s a things-fall-apart vibe in the film’s scenes of random violence that’s genuinely unsettling—a fear of being snuffed out simply because you’re there.”

Sinister children are another evergreen horror theme, but the class of ’76 was particularly memorable. The Omen is the big one, imagining the Antichrist as a creepy moppet whose apocalyptic destiny is overseen by shadowy protectors, including one very nasty nanny. The film had classy actors like Gregory Peck and Lee Remick, and it presented everything with great seriousness—a deliberate move by director Richard Donner (who’d go on to make Superman, The Goonies, and the Lethal Weapon movies), who took out all the original script’s “cloven hoofs and devil-gods and covens” and tried to make each murder in the film feel like “it could have been circumstantial.” There’s that random violence again.

Contemporary reviews were dismissive; the New York Times called it “a dreadfully silly movie” and “the kind of movie to take along on a long airplane trip,” which is an especially odd thing to say in 1976. More recently, though, critics have pointed out The Omen’s popularity upon its release had as much to do with its cultural context as its over-the-top bloodshed. As Cinefantastique Online wrote in 2008:

During the mid-1970s, when the Cold War was in full swing, with the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. seemingly on the verge of obliterating each other with nuclear weapons, this apocalyptic tale tapped into the zeitgeist; the ending, with Damien living on to bring about world destruction, seemed less like a contrived twist than a reflection of reality.

That’d be chilling enough coming from one movie, but 1976 was full of child-centric horror movies that allowed the forces of evil win in the end: Alice, Sweet Alice (a notable pre-Halloween slasher film) and The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane (with Jodie Foster) are both about tweens with alarmingly violent tendencies. The Spanish import Who Can Kill a Child? takes place on an island overrun with murderous youngsters, and it doesn’t end well for the pregnant woman who dares to come ashore.

Carrie is sort of a special case, because really, you want telekinetic misfit Carrie White to get bloody revenge on everyone. The film was well-received by critics at the time—Brian De Palma fan Pauline Kael called it “the best scary-funny movie since Jaws”—and it’s remained a classic. As Bright Lights Film Journal points out, “this universal tale about growing up different continues to make ‘topical’ and ‘relevant’ contact with cultural issues even today in zingy and unexpected ways,” including extreme Christian fundamentalism and schoolyard killing sprees. In 1976, it spoke to audiences who related to Carrie’s struggles—but also envied her powers, a defense mechanism against whatever unknown threat (among all their many fears) might strike first.

As critic Wood wrote in 2001:

In the ’70s one felt supported by, at the least, a general disquiet and dissatisfaction, at best a widespread desire for change, which came to a focus in the period’s great social movements—radical feminism, the black movement, gay rights, environmentalism. Those movements still exist but have lost much of their momentum, perhaps because of the advances they made: advances that have, to some degree, been recuperated into the Establishment at the cost of losing their dangerousness. Perhaps the new American administration will goad people into a new sense of outrage and fury, but it may take the equivalent of the Vietnam war.

That “new American administration” he mentions is the changeover from Bill Clinton to George W. Bush; the essay, published in July, predates 9/11 and the deluge of real-life horrors that followed. But it might just as well be referring to 2016—and the palpable fear that currently seems to be swelling in the real world, which will no doubt continue to bleed into today’s horror movies. We’ll be watching.