At first, things could actually be rather beautiful: worldwide auroras! A brighter sun! But then things would rapidly get ugly, with the breakdown of communications, rolling power outages, and a burning away of the ozone.

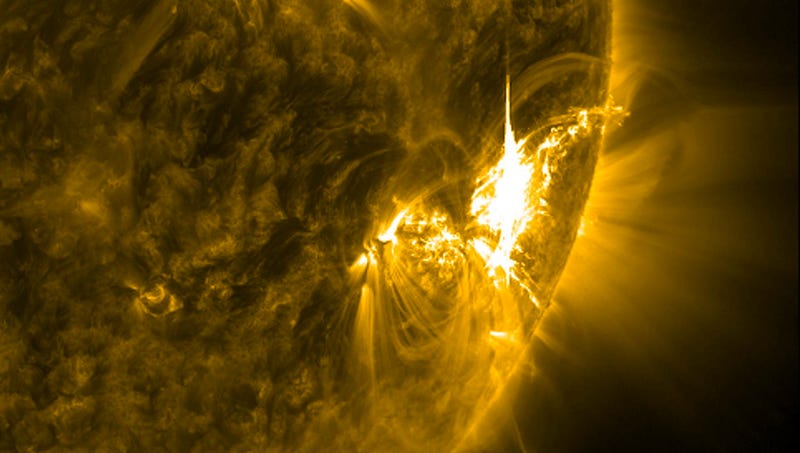

We see solar flares all the time on our sun. There’s nothing unusual about them, or the lovely auroras that they leave in their wake. But when we look at other stars out there, we see not only solar flares but also the occasional “superflare”—flares that are not only large, but dwarf everything we’ve ever seen from our own sun, sometimes up to 10,000 times the size.

But what if we saw something like that not through the distant, indifferent eye of the telescope, but right above through our own unaided eyes?

The idea is not absurd. Previous studies

The answer: not likely. Almost all the super flares the researchers looked at came from stars with much stronger magnetic fields than our own sun. A small but significant portion (about 10 percent), however, had magnetic fields of about our own sun’s size, meaning that the field is at least theoretically strong enough to generate a superflare.

So what would it look like in the unlikely event that we did get one?

Christoffer Karoff of Denmark’s Aarhaus University, told Gizmodo a little more about just how such a massive solar flare would play out. He sketched out a timeline of what we could expect to see from our Earth-bound perspective —from the worldwide auroras, to the breakdown of our tech, to the final return to normalcy.

During the superflare, the Sun would light up and become a few times brighter for the half an hour the flare would last. The superflare would likely also be associated with a lot UV and X-ray emission, but our ozone layer would shield us for most of this.

After a day or so the Earth would be hit by the plasma from the superflare. First the plasma would destroy all satellites around the Earth, shotting down GPS and communication system. Then particles from the plasma would get accelerated in the Earth’s magnetic field and cause world wide auroras, as it was seen after the 1859 solar storm (which was significant smaller than a superflare). The plasma would also affect the Earth’s magnetic field so much that it would stars to induce electric currents in our electric infrastructure. This would likely led to power outage world wide, as in happened in Quebec during the 1989 solar storm. The Earth atmosphere would also be effected, so radar and radio system would be down, as in happened in Arlanda airport in Stockholm last year.

But the worst thing would be our ozone layer. Some simulations predict that the 1859 solar storm (the Carrington event) was associated with a 5% reduction of the ozone layer. Though these simulations have been criticised, it is still safe to assume that a superflare would cause a much larger reduction of the ozone layer… 5-10-50%. Our ozone layer protect us from 99% of the UV radiation from the Sun, so skin cancer could wipe out a significant fraction of the population and it is not clear what the increased UV radiation would do to animals and plants. The ozone layer would likely take more than 5 years to rebuild, and after that things should be back to normal.

Both these theorized effects and the possibility of a superflare on our sun are fairly unlikely events. So we can hold off on on our stockpile of SPF 10,000 and generators—for now. But the threat of what could happen if a solar flare did strike is still enough to make us feel a little uneasy about our sun.