Marvel’s most important black superhero has evolved a lot over 50 years. The Black Panther has gone from being an under-utilized figure in the background of Avengers group shots to arguably being the most fearsome strategist in the Marvel Universe. His elevation to Marvel’s top tier is a fascinating meta-story.

To me, the core dynamic that makes the Black Panther work comes from a set of paradoxes churned up by the collision of real world and fictional tropes and stereotypes. That tension shows up in the first panel of the first page of Fantastic Four #52, the 1966 issue where Stan Lee and Jack Kirby introduced the character.

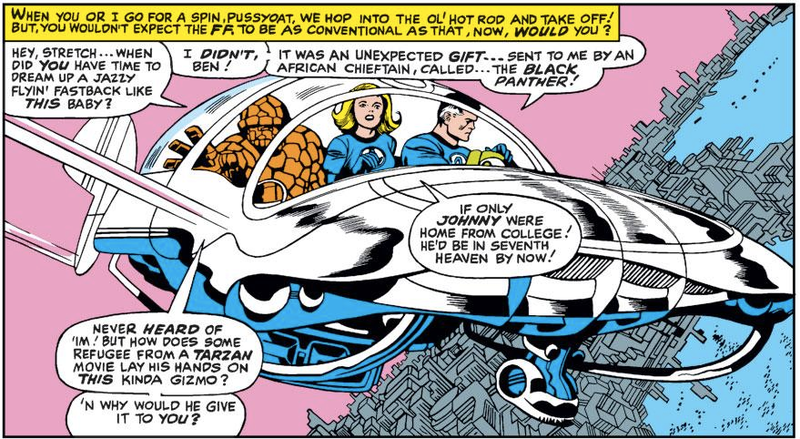

As three members of Marvel’s First Family fly in an advanced aircraft provided by the Panther, Ben Grimm wonders aloud, “But how does a refugee from a Tarzan movie lay his hands on this kinda gizmo?” Let’s count the assumptions in that sentence:

• that the Africans in a Tarzan movie are a reference point or even representative of anything

• “lay hands on” strongly implies that the Thing thinks that there’s no way an aircraft this advanced could come from Africa. He had to have come across it from some other, more sophisticated individual or culture.

A later panel hits the same note of incredulity, this time voiced by the Human Torch.

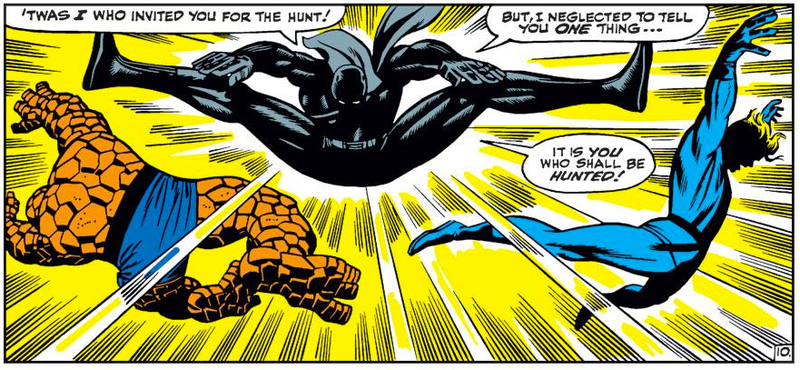

Now, it should be noted Lee and KIrby were doing their job as storytellers here, crafting a set of expectations for the reader that they’d upend for a surprise later in the issue. It would turn out that T’Challa is in fact a genius on par with Reed Richards and cunning enough to trap and nearly defeat the Fantastic Four in battle.

But the raw material for those expectations was drawn from the real world. The Tarzan movies Lee references were only the most recent version of the idea that Africa was a wild Dark Continent populated by uncivilized “savages”. That belief was taken as a given for centuries by that point and still persists today. So it’s laudable that two middle-aged Jewish men working in 1966 New York City dreamed up an African superhero king who rules over an technologically advanced nation. But the way they did that simultaneously reinforces the very same stereotypes and value judgements the Black Panther was supposed to dispel.

From the first time the reader sees and hears Wakanda, the fictional country is a mix of paradoxes. It’s super-advanced, has never been colonized and hides from the rest of the world. It’s almost as if Lee and Kirby knew they had to temper the idea of a black super-society with the element of making it hidden and doubling down on nativism. While Wakanda is shown as being ahead of much of the world with regard to technology, the rest of its culture gets portrayed with outdated stereotypes.

The first two stories featuring T’Challa beg the question: what were Stan and Jack trying to accomplish when they created the Black Panther? As is often the case in many instances from Marvel’s early days, debate swirls around exactly who did what insofar as initially conceiving characters. Whether it was Lee or Kirby who first came up with T’Challa, whoever did so with the aim to come up with a superhero who didn’t look or act like the other characters in their stable. There was likely a mix of altruistic and business-minded inspiration at play. The Panther’s first appearance happened during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, and Marvel’s editorial staff were probably watching the newscasts that showed black Americans getting brutalized by police as they sought to change the prejudicial law of the land. Given the times that he was created in, it’s very plausible that The Black Panther was Lee and/or Kirby’s way of saying that a black person was as capable of being a hero as their white characters. Even more daring, the Panther seemed to be more cunning and intelligent than some other heroes. Yet, making him African gave Marvel license to call on the exoticization of non-American black people. T’Challa wasn’t like the black folk American readers were used to and this notional distance kept the Panther away from the marches, murders and discrimination in the United States. In the early part of his publishing history, he’d be a character that funneled escapism more than commentary.

The debut storyline for the Black Panther created a template for many subsequent turns in the spotlight. Many of his most significant spotlights were pegged to social justice issues. He was central to these plots insofar as he was one of very few black characters through which racial tensions could be channeled. Ultimately, however, it was mostly the white personas in these adventures who experienced character growth. The Panther remained safe, stoic and a little hollow.

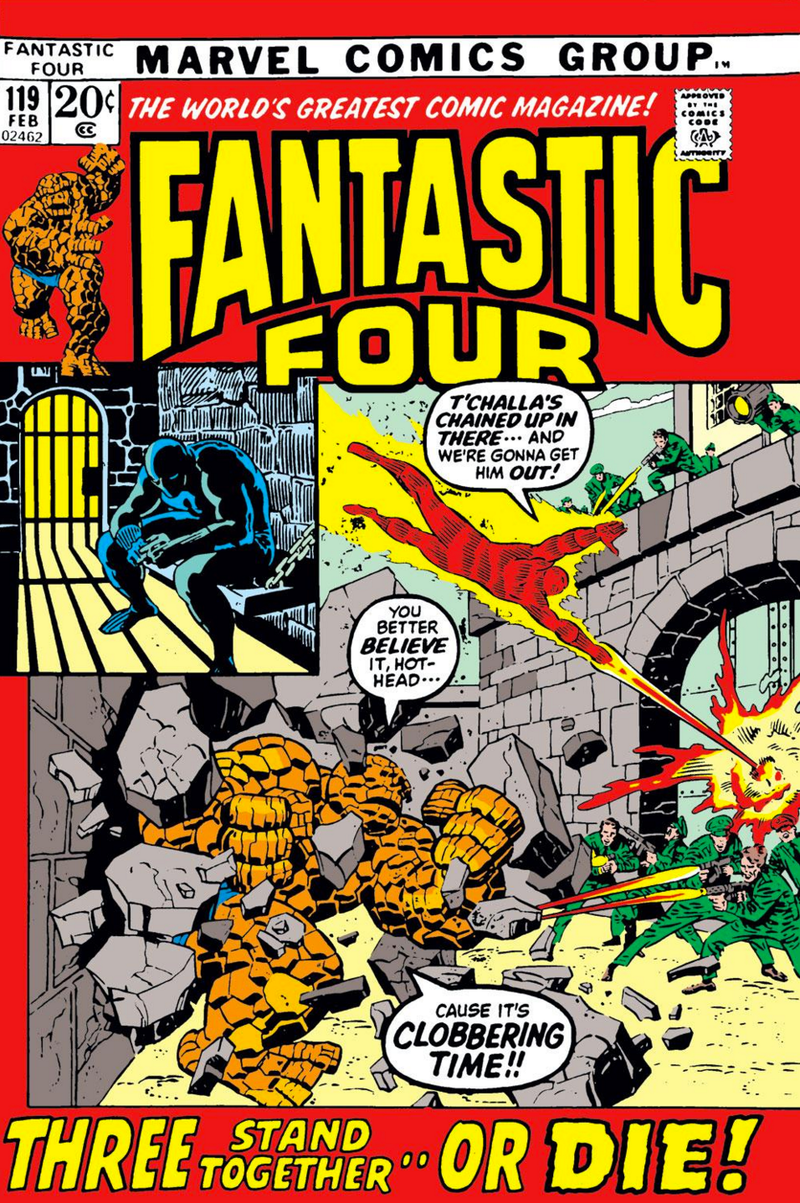

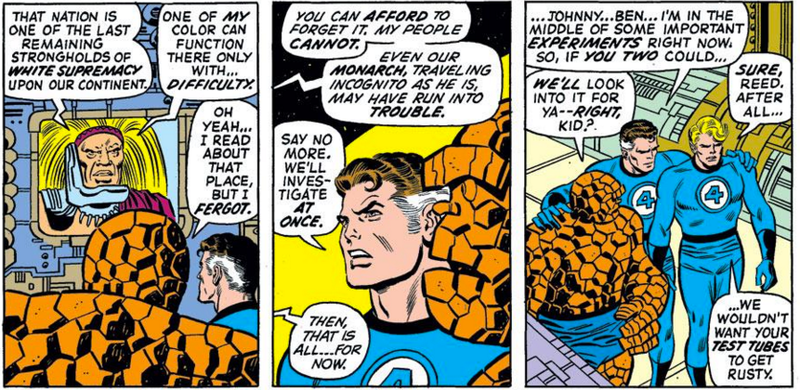

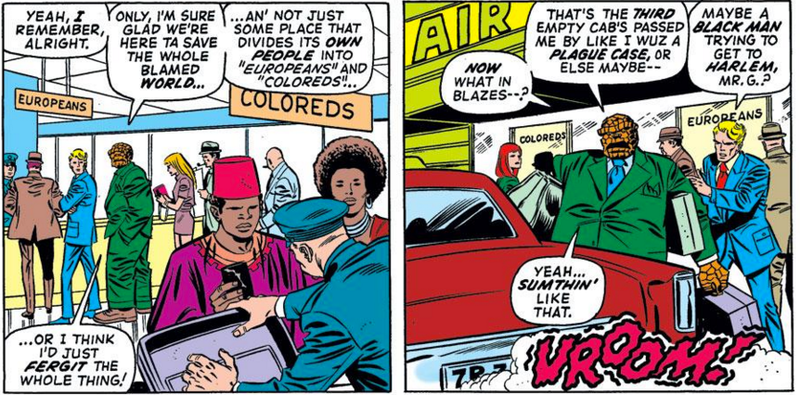

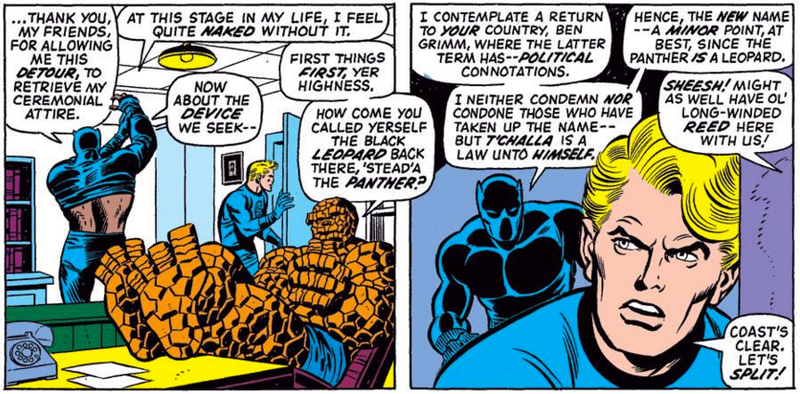

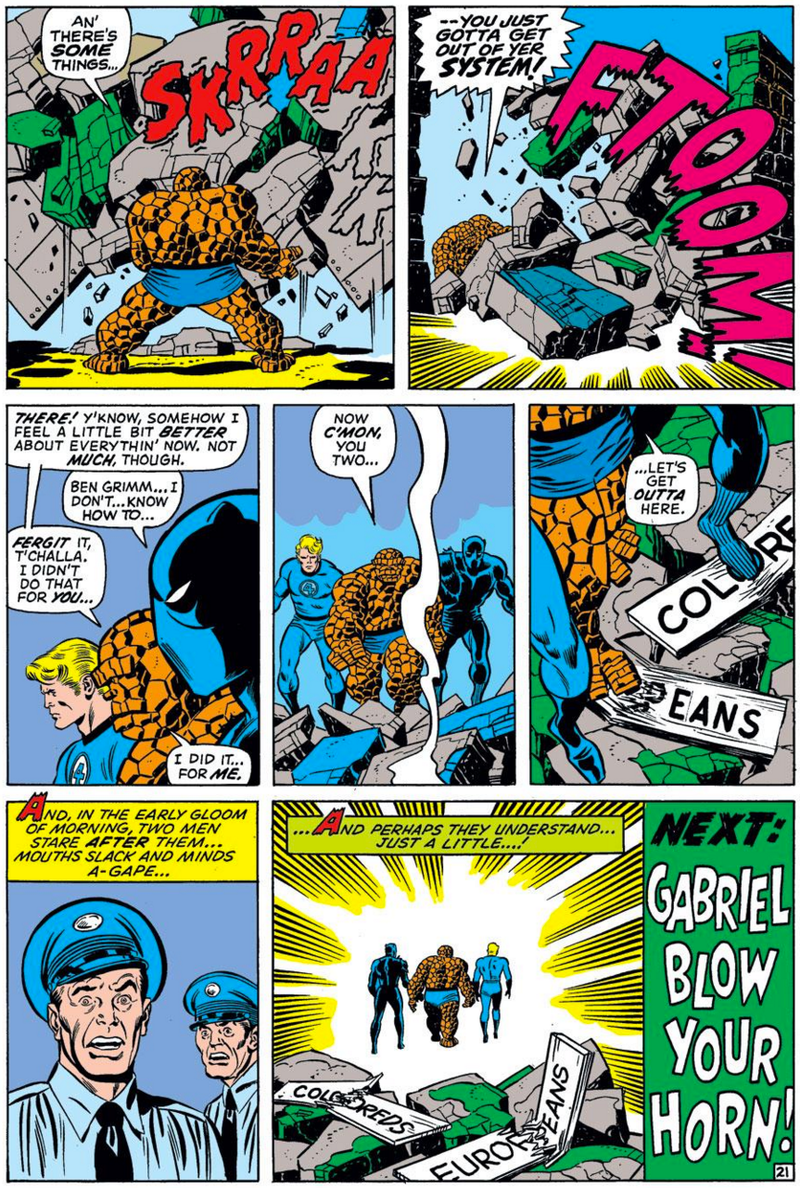

Fantastic Four #119 is an example of this paradigm. Written by Roy Thomas with art by John Buscema, Joe Sinnott and Artie Simek, the one-off story used the Panther was used to address the racial politics of the day. T’Challa is trapped in the fictional country of Rudyarda, which is a clearly a stand-in for South Africa. (The country’s name is a reference to Rudyard Kipling, author of The Jungle Book and, relatedly, the poem “The White Man’s Burden.”)

On their way to help T’Challa, Johnny Storm and Ben Grimm stop a skyjacking. A frequent occurrence in the 70s, these airborne crimes were often politically motivated. The sequence serves a thematic underpinning to the Fantastic Four members’ rescue mission, showing them opposing people who’d commit violence in the name of politics.

Roy Thomas uses T’Challa to comment on the racist evils of real-world apartheid, but it comes during a time when Marvel changed the character’s superhero name to the Black Leopard to avoid any associations with the Black Panther Party. Once again, seemingly noble intent collides with business calculus.

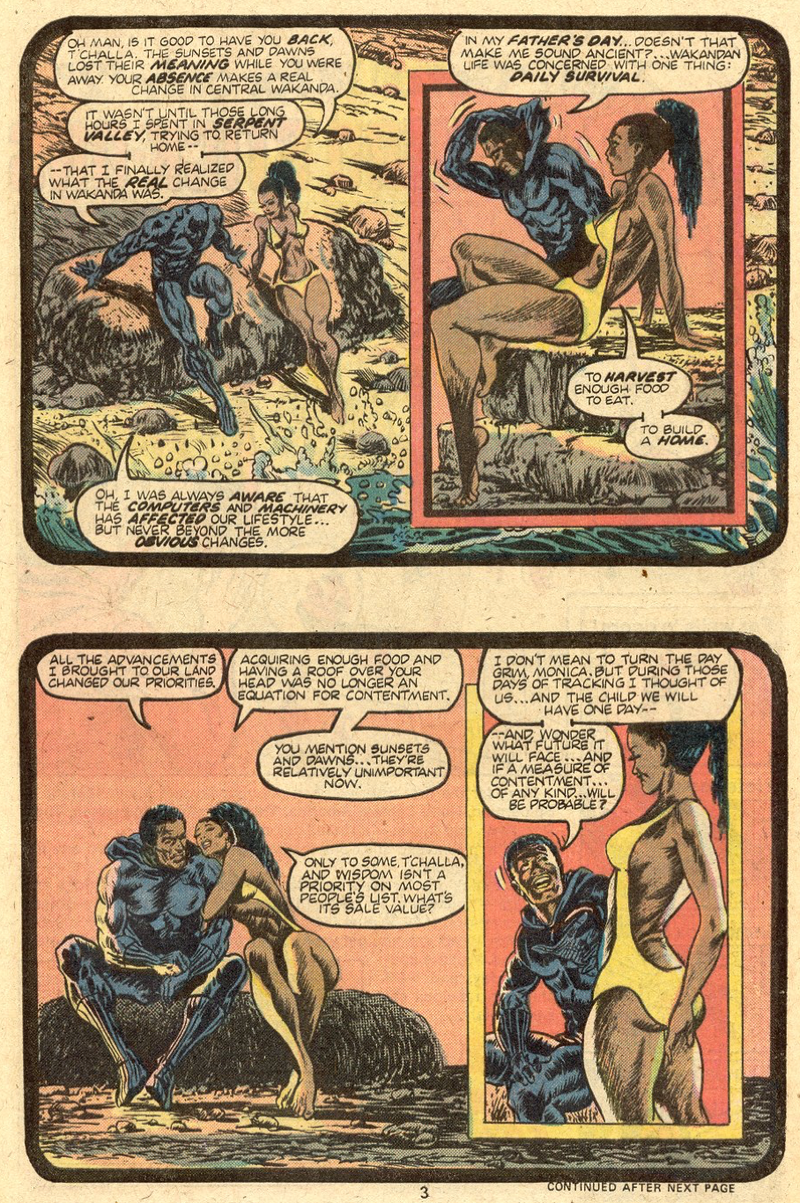

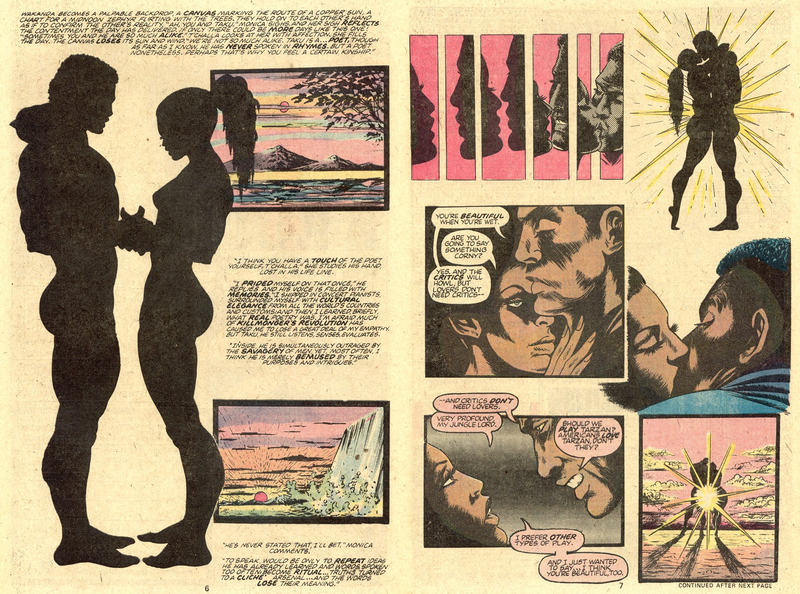

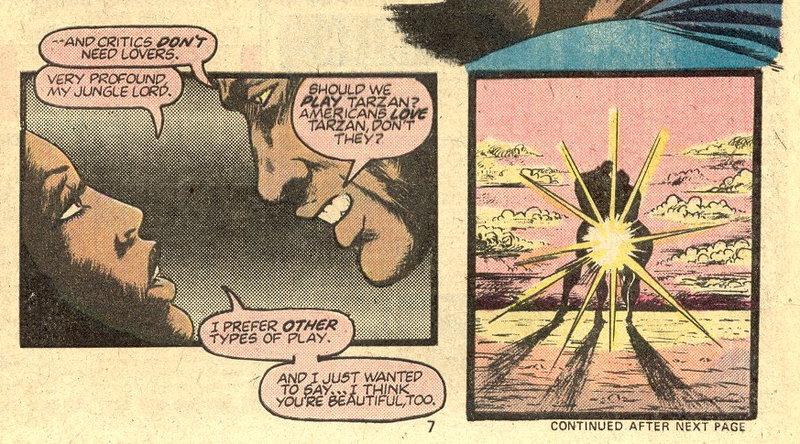

The Panther didn’t really come into his own until 1973, when writer Don McGregor began a long relationship with the character. Over the course of 20 some-odd years, McGregor’s three classic storylines—Panther’s Rage, Panther’s Prey and Panther’s Quest—added depth to Wakanda and the man who ruled it. In Panther’s Rage, the country was shown to harbor a large xenophobic streak, as T’Challa’s engagement to black American Monica Lynne was cause for outrage.

The hints of isolationism and exceptionalism from the early Lee/Kirby stories bloom into full-grown traits under McGregor’s watch. As the story focuses on T’Challa’s inner circle and the country’s royal court, you get the sense that many Wakandans do think they’re better than the outside world.

The bulk of these Panther stories happen almost entirely in Wakanda and feature a cast that’s mostly black. Here, T’Challa’s worth isn’t measured by how much he helps white characters. It’s how he handles the responsibilities of being a monarch and an adventurer and the insurgency fomented by archenemy Erik Killmonger that’s the main concern. His own struggle to balance love and duty drives the drama.

These comics are relics of their time, chock a block with captions and word balloons and dizzying page layouts by Billy Graham. But the ambition here felt organic, solely concerned with imagining how heavy a crown would be on a superhero who’s also a king. By scuffing Wakanda’s gleam with melodramatic sociological subtext, the creative team humanizes the Panther and his realm. McGregor’s Wakanda feels like it might be influenced by what was happening on the real-world African continent at the time. Former colonies had started exercising sovereign rule, and the vast amounts of money generated by natural resources led to bloody coups and rampant corruption. African countries were as susceptible to the foibles of the human soul as anywhere else. These stories are where Wakandans stop being refugees from a Tarzan movie.

Even the fact that he’s a king speaks to the idea of what monarchy meant in the 1960s. Rule by bloodline is an antiquated mode of governance. Backwards, even?

Wakanda was a way for McGregor to ruminate on self-determination and the tug-of-war between modern life and traditionalism. The specter of colonialism hovers over the Panther’s origin story. His father is killed by Ulysses Klaw, a mercenary who wants to claim the super-metal Vibranium as his own, and T’Challa is left alone to figure out how to move his life and the country forward. In the McGregor stories, the outside world was knocking on the nation’s door and it was up to T’Challa to decide how to answer. But, for all the focus on T’Challa’s homeland, he didn’t leave the king out of America altogether.

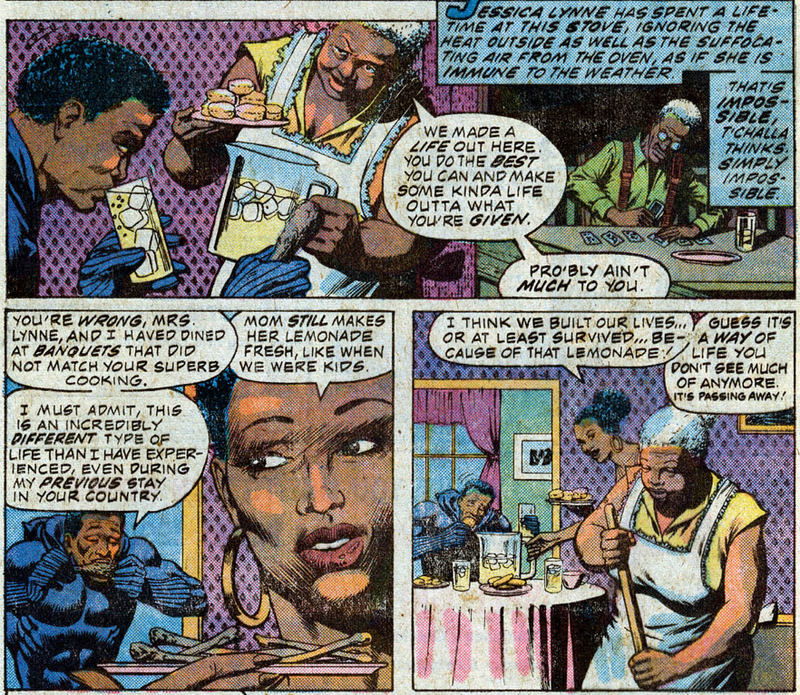

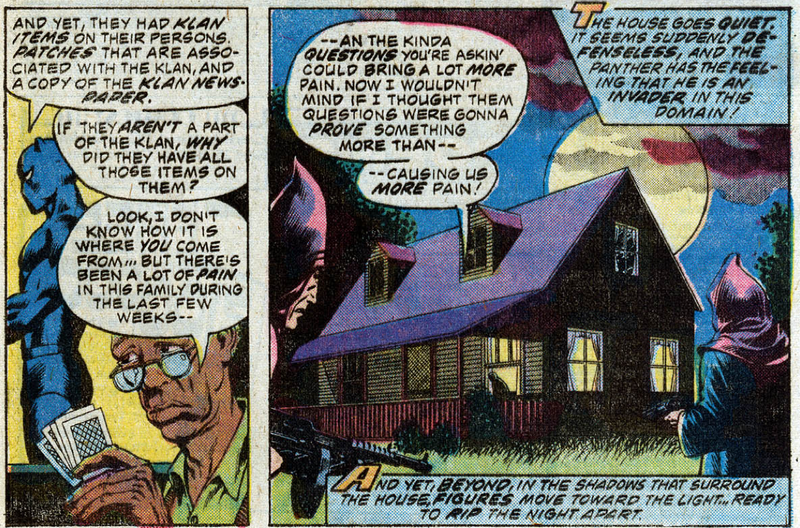

The Panther vs. The Klan story from 1975 hits some of the expected beats, showing T’Challa grappling with avatars of white supremacy in its most naked form. But it also finds unexpected poignancy in taking time to sketch out moments of black life in the south...

...and, better still, showing how an African man doesn’t automatically relate to that kind of existence. When T’Challa brings up the death of Monica’s sister to the Lynne parents, they ask him to realize that fighting for justice is going to disrupt the uneasy quiet of their lives.

Discussions centered on representation in superhero comics really didn’t come to the foreground until the 1990s. But there was always a black audience who was paying attention to how brown-skinned people were portrayed in the books they bought. Seeing a moment where a black superhero breaks down a burning cross and beats up a group of Klansmen held power.

McGregor’s follow-up arcs had T’Challa dealing with more challenges to his rule and the stability of Wakandan society. The 1989 serialized saga Panther’s Quest led T’Challa to South Africa to rescue his stepmother Ramonda (who also was born outside of Wakanda) from a powerful white supremacist who’d kidnapped her, while the 1990 Panther’s Prey miniseries had crack cocaine infiltrating the seemingly perfect kingdom.

When McGregor wasn’t writing Panther stories, the character didn’t have a sole dedicated caretaker for many years. He’d show up as a guest star in Daredevil, Fantastic Four or The Defenders, usually in a plot that had something to do with Vibranium. Without a dedicated caretaker, Wakanda’s status quo got milder, as infrequent spotlights on the realm only allowed time to show it as a gleaming wonderland. The Panther, too, felt less interesting as his appearances left little room for character development. He slipped back to feeling like an editorial device again, and less like a well-rounded character.

A 1998 miniseries by Peter B. Gillis and Denys Cowan bucked that trend and pit the Panther against apartheid once more. This story saw the Panther God severing its link with T’Challa because of the king’s inaction against the racist oppression in Azania. This fictional country was another thinly-veiled version of South Africa, one that had its own superheroes.

The florid writing style here echoes McGregor but presents T’Challa as more torn than in previous stories. It’s a frenzied story where he fights battles of perception, political strategy and spiritual faith. Black Panther 1988 burnishes the character’s status as a symbol but leaves him more fallible as a man.

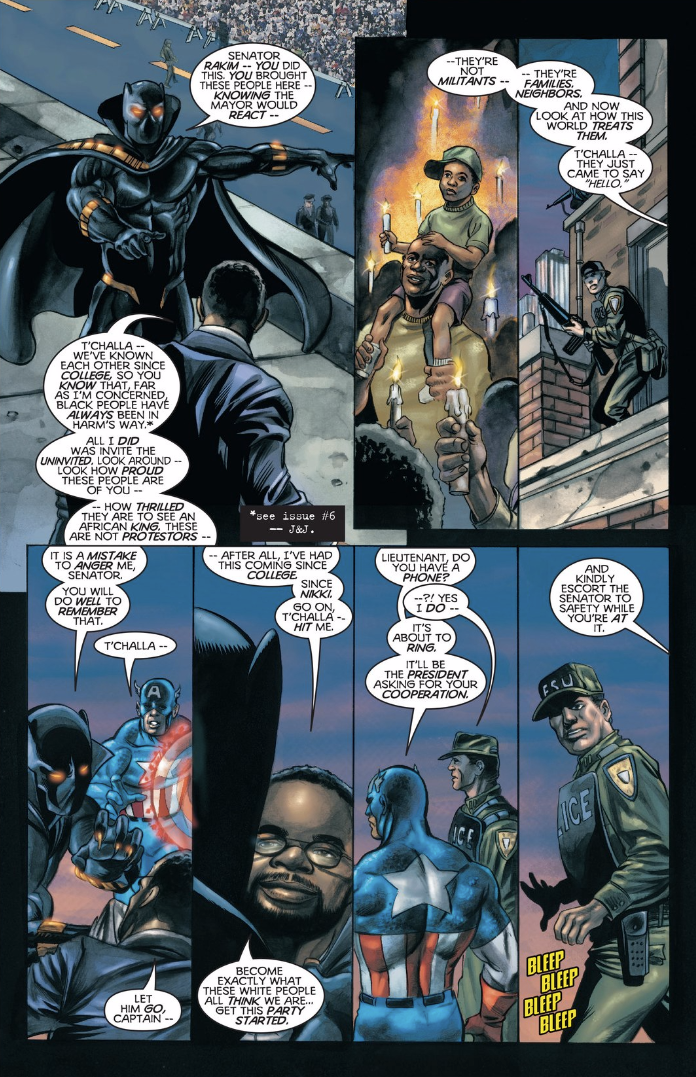

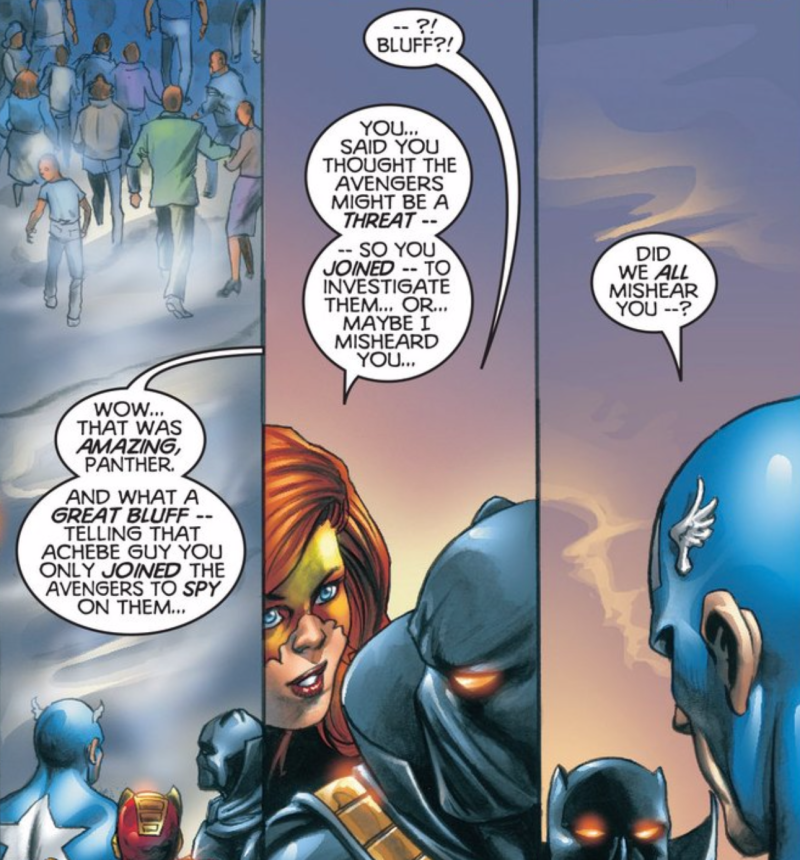

That fallibility melted away when Christopher Priest started writing his acclaimed Black Panther series

Over the course of five years, the series posits that the world’s never really known who the Panther was and what he was capable of. Revelations that T’Challa joined the Avengers only to spy on them rewrote the collective understanding of the character, paving the way for him to become an even bigger player in Marvel’s fictional landscape.

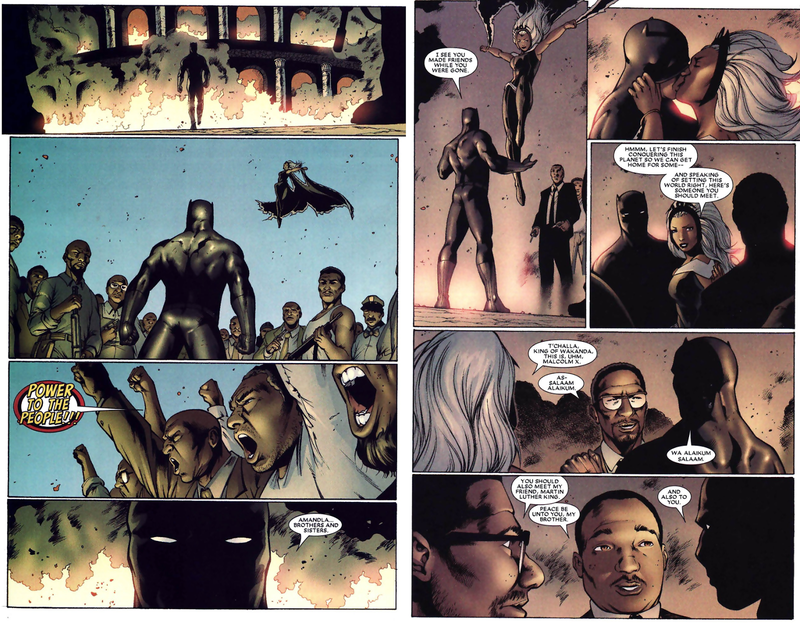

Priest’s run was followed by a series helmed by Hollywood producer Reginald Hudlin. I’m not a fan of Hudlin’s interpretation but recognize that his loose-limbed approach tried to channel a sort of black experience and iconography that he felt was missing from superhero comics.

So, even if I don’t like the fact that he had T’Challa meet Skrull versions of Malcolm X and The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King who worked together to overthrow a corrupt government on a distant planet, I can respect why he did it.

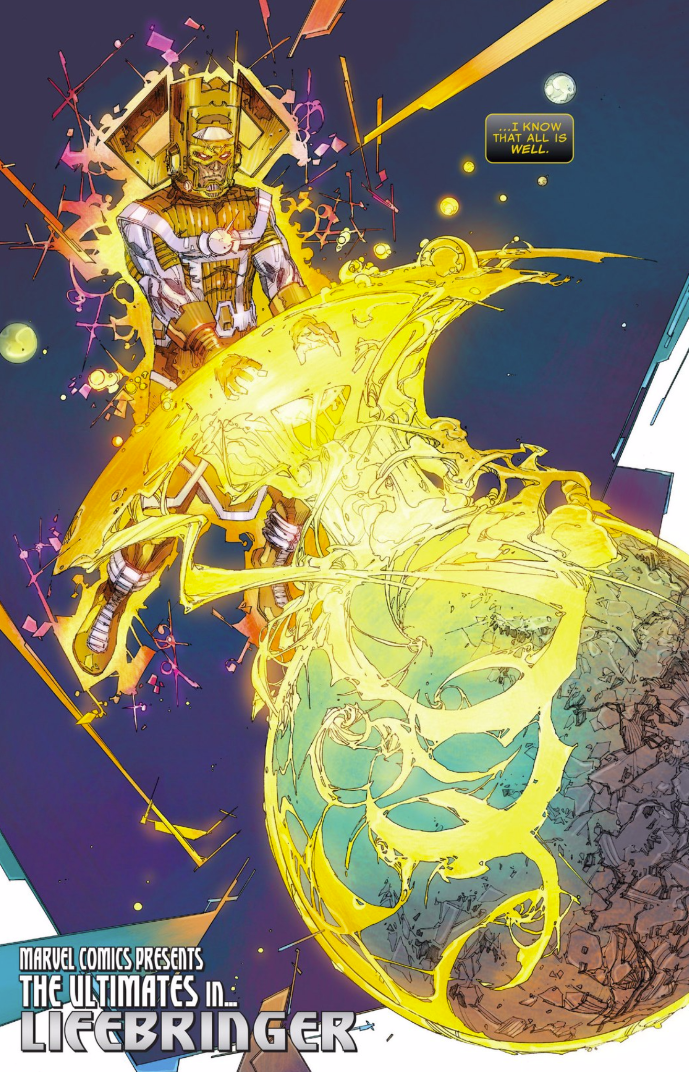

T’Challa’s next big turn on the Marvel stage came in the New Avengers

His existential crisis led to him being cut off from his ancestral lineage, but the Panther has come out on the other side of helping save the Marvel Multiverse in Secret Wars. He’s leading the best team

The Black Panther may have been born from a mix of white guilt, black empowerment fantasy and market opportunism. But he eventually transformed something more than the sum of those parts. T’Challa became a character who was almost always used in service of an agenda: to make his publishers look more diverse, to let creators of color touch a character that they can speak their experience through, to show the polyglot of the black diaspora is not a monolith and that there can be tension and/or reconciliation amongst its components.

When the Black Panther gets introduced to the Marvel Universe, he’ll be serving some the same ends as he did in his first comics appearance. He’s also got a new series starting next month, written by award-winning author Ta-Nehisi Coates