A new study has shown that people with Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), associated with bursts of overblown aggression, are twice as likely as healthy people to have Toxoplasma gondii. This parasite, famously carried by cats, has been shown to mess with the neurochemistry of mice. Could it be doing the same to us?

Published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, this new study builds on earlier work by Emil Coccaro, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Chicago, who has been studying people suffering from IED since 1991.

Coccaro recruited his subjects by putting out announcements in newspapers and journals, looking for people who regularly “blew up” as often as every few weeks, or as infrequently as every few months. To qualify as IED, these losses of temper have to be out of proportion with the offense that caused them. The outbursts must have led to consequences, like lost jobs and broken relationships, and they couldn’t be associated with an underlying disorder like depression or anxiety. A person with IED isn’t “snapping” under strain. They feel normal until something angers them, at which point they react with far too much aggression.

If that sounds like a convenient excuse, there are several mitigating factors to be considered. “It is very much a biological problem,” Coccaro told Gizmodo. It tends to run in certain genetic lines. Like many diseases, it has a typical age of onset—the early teens. And it is associated with physical traits, like reduction of gray matter in the brain.

The second factor is that people with IED are not wild-eyed psychos who shoot people in the face over a parking space. “These are your neighbors. They’re people you work with,” Coccaro explained. For the most part, IED contributes to people yelling and screaming, not committing violent crimes. That isn’t to say that people with IED don’t occasionally commit crimes, but according to Coccaro they are “absolutely” responsible for their behavior when they do, and should face the consequences for their crimes.

“Lawyers call me,” he said. “And I tell them not to use it during the trial. Save it for the penalty phase, to make sure he gets treated.”

And that would be the third factor. Intermittent Explosive Disorder isn’t just an excuse to wave around after a person has behaved badly; it’s an avenue for improvement. If someone has a biological problem, they can be treated. However infuriating it is to deal with someone who throws a tantrum over small setbacks, it’s better to take steps to make sure it doesn’t happen again than to simply write them off as a terrible human being. The fact that Coccaro got responses to his announcements shows that many people with IED want to do whatever it takes to get better.

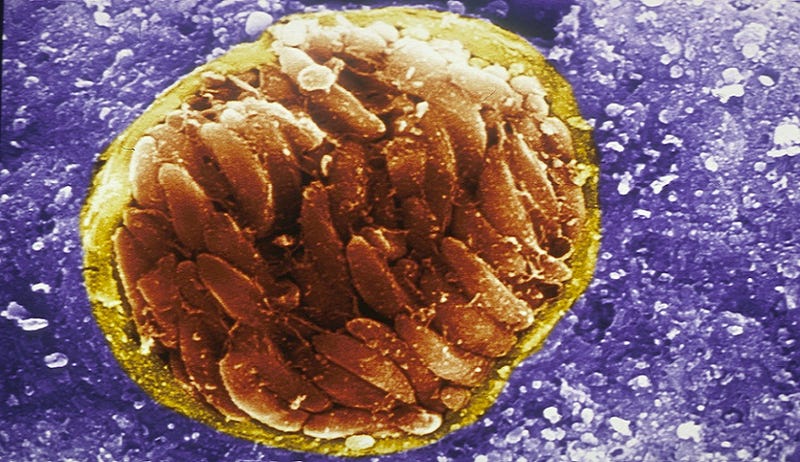

Toxoplasma gondii made a name for itself when scientists noticed how the parasite jumped from the intestines of cats to mice. The protozoan has been shown to make rodents more impulsive, more exploratory, and in general more likely to run out into a room and get eaten by a cat. But the microbe isn’t confined to cats or rodents. It can infect any warm-blooded animal, according to Teodor Postolache, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Pregnant women have been warned about Toxoplasma gondii because an infection can harm a developing fetus.

Postolache has found links between Toxoplasma gondii infection and increases in migraines, seizure disorders, car accidents, schizophrenia, and increased rates of suicide. He believes it’s “possible”—although he stresses that there is no definite proof—that the parasite is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

For this most recent study, Coccaro, Postolache, and several other researchers examined the rates of Toxoplasma infection in 358 subjects. They found that healthy people had an infection rate of 9 percent, while people with IED had an infection rate of 22 percent. What’s more, people infected with the parasite, whether they had IED or not, had higher levels of anger and aggression, but not depression or anxiety. This indicates that the parasite may be a major factor in causing IED.

Both Postolache and Coccaro stress that this does not prove that Toxoplasma gondii causes IED. There are other possibilities. For example, people who are more impulsive, or feel more aggressive, may eat more undercooked meat—a major infection vector for Toxoplasma gondii.

According to Postolache, there are two pathways by which the microbe might cause mental issues. Toxoplasma gondii is tough to clear from the body. For the most part, the immune system represses it, much like it represses herpes. When the immune system weakens, the microbe can reactivate, and cause mental problems. Proving this would mean selecting individuals who have frequent “flare-ups,” and trying to suppress reactivation. It’s also possible that the immune system itself might be causing the mental problems as a result of fighting the infection. Researchers might control the immune response, and see if that has any effect on a person’s mental state.

The next step is studying the health of the Amish population of Maryland. The Amish population has a relatively high infection rate of Toxoplasma gondii. Postolache wants to study genetic lines, to see if genes are a factor in mental health disorders, and also study households to see if there are different risk factors that increase infection rates.

Over time, it might be possible to “catch the moment” when a person becomes infected with the parasite, and see if they experience changes in their mental state, or change their behavior, at roughly the same moment. That, he believes, would be the best way to prove, or disprove, the idea that Toxoplasma gondii, causes mental problems as well as physical ones.

If it does, and if those problems can be treated, we might one day live in a much happier and calmer world.