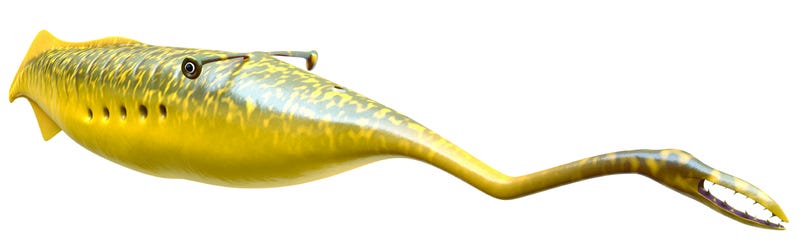

A retractable, jawed proboscis. A lithe, slippery body. A tiny dumbbell with slow blinking eyes. Meet the Tully monster, an actual sea creature that seems to have sprung to life out of a drug-induced fever dream involving vibrators and surgical tools. At long last, scientists think they know what kind of creature it is.

Measuring up to 10 centimeters in length, Tullimonstrum gregarium swam about in the shallow Carboniferous oceans covering much of the midwestern United States 300 million years ago. The first fossil was discovered by amateur collector Francis Tully, in 1958. Bewildered by what he’d dug up, Tully brought the specimen to paleontologists at the University of Chicago, who were no less perplexed. “From the beginning, the Tully monster was like nothing we’ve ever seen before,” Yale University paleontologist Victoria McCoy, who led a new analysis of Tully monster fossils out in today’s Nature, told Gizmodo.

For more than fifty years, biologists have tried to fit the beast somewhere on the evolutionary tree of life, grouping it with everything from worms to snails to various extinct invertebrates. It’s not hard to see why scientists struggle to explain the Tully monster. It looks like a hand blender mated with a salamander.

But now, McCoy and her colleagues have a more logical answer. Analyzing over 1,200 fossil specimens, the team discovered that the Tully monster possesses a notochord—a primitive backbone found in all embryonic and some adult vertebrates. “This is a really important feature, because once you identify it, you’re guaranteed to be looking at a vertebrate,” McCoy explained.

Other telling anatomical features include gill pouches, teeth made of keratin, and a tail fin with dorsal and ventral lobes that the Tully monster no doubt used to propel itself forward toward its next, terrified meal. Based on these characteristics, and using modern tools for reconstructing evolutionary relationships, McCoy and her co-authors conclude that Tully monsters are probably a cousin of lampreys

“This discovery will be really important for understanding the evolution of lampreys,” McCoy said, noting that while all lampreys look “basically the same” today, they might have been a far more diverse group hundreds of millions of years ago. The Tully monster is, as McCoy puts it, “a tantalizing glimpse at the idea that maybe there are a whole bunch of really weird lampreys out there in the fossil record.”

Only time, and more fossils, will tell. Alternately, the scientists could have it all wrong. We could be looking and the lovechild of a drunk Nessie and a radioactive sea anemone. I still haven’t ruled that one out.

[Nature]