Twenty years ago, a change was made to how we did food poisoning testing. That change prevented over a quarter of a million cases each year, and it may also suggest how we could stop more cases in the future.

The CDC just finished an evaluation of their PulseNet program—a system that links national labs that do food poisoning testing—and said that by giving all the labs access to each other’s DNA tests on food bacteria they were able to stop 270,000 cases of food poisoning each year. The results of their analysis, along with an economic assessment estimating that those prevented cases save $500 million a year, was published today in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

The real takeaway here, though, is about one of the underlying causes of food poisoning and how we can stop even more cases before they start.

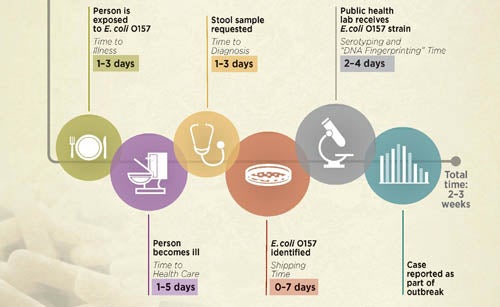

The timeline (i.e. how long it takes from the time a person eats something contaminated to when they actually gets sick) is still the real problem in most large food poisoning outbreaks. Look at Chipotle

This lengthy timeline represents only a single case. So linking cases to figure out whether people were hit with food poisoning from the same source can take even longer. By the time a confirmed diagnosis is out, whatever it was that was making people sick had long ago all been eaten up (and possibly made even more people sick). The root source of the contamination was also never cleared up, and so it could strike again. Speed is incredibly important, and anything that can shorten the timeline in diagnosing and linking food poisoning cases can also help prevent them.

Preventing food poisoning is often presented as a question of best kitchen practices, and certainly that’s part of it. But sharing information in realtime—including not just lab results but also tests of ingredients and tests on the kitchens themselves—may turn out to be just as essential to stopping food poisoning before it starts.