Lucifer. Damien. The Witch. A new TV show based on The Exorcist. Hell, even Once Upon a Time

Taken as a whole, George Case’s Here’s To My Sweet Satan: How the Occult Haunted Music, Movies, and Pop Culture, 1966-1980 is more of an overview than a deep dive. Particularly for anyone who’s already studied up on rock ‘n’ roll history and horror cinema, the music and movie chapters don’t impart much new information. This is clearly due to space considerations—Case’s previous works include a bio of avowed Aleister Crowley enthusiast Jimmy Page, which no doubt goes into way more detail than the few pages afforded here.

http://www.amazon.com/Heres-My-Sweet...

http://www.amazon.com/Heres-My-Sweet...

But Here’s To My Sweet Satan can hardly be accused of merely skimming the surface. It’s well-researched, and an excellent primer for anyone who’s curious about the occult’s influence on pop culture; no doubt its robust bibliography will lead many a reader to delve deeper into whatever portion of the book catches his or her attention the most. And though its nearly 15-year span of coverage—and the sheer breadth of its subject matter—means most topics don’t get too much detail, even veteran scholars of the weird will likely unearth some new factoids.

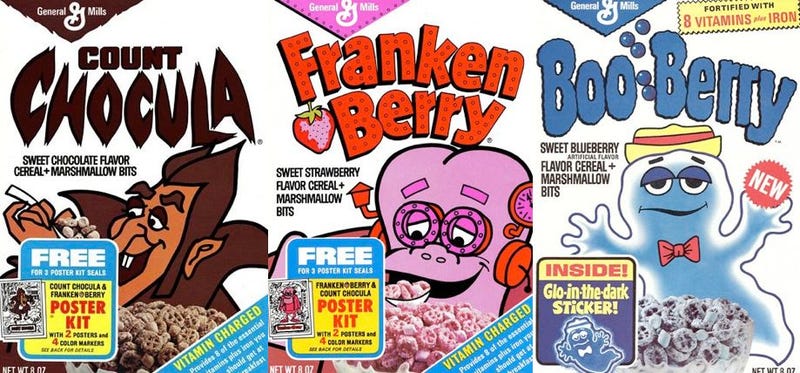

Particularly inspired is the chapter on how the occult trickled into kiddie culture in the wake of its breakthrough into mainstream adult entertainment. While parents paged through Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist (and shrieked through their blockbuster film adaptations), their kids could dine on horror-themed breakfast cereals. Even General Mills’ official blog on the history of Count Chocula and friends (introduced in 1971) doesn’t go as deep as Case does, reaching out directly to the woman who came up with the funny monster characters as part of an advertising strategy to compete with Cap’n Crunch. And it’s just one relatable, and especially silly, example of how prevalent the supernatural had become at that time.

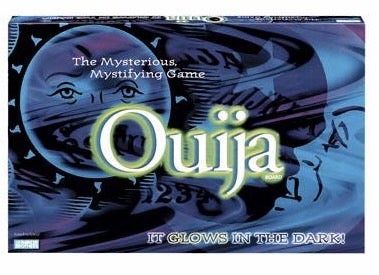

The chapter on children, “Little Devils,” also highlights ghoulish toys of the era like Parker Brothers’ mass marketed Ouija board (an Ouija board being, of course, the method by which The Exorcist’s unfortunate preteen contacts a certain Captain Howdy. Today, it’s still a popular item for Hasbro, which acquired Parker Brothers in 1991), and Milton Bradley’s Shrunken Head Apples DIY kit, which was peddled in TV ads by horror icon Vincent Price. And, of course, Dungeons & Dragons, which rose to prominence in the late 1970s, gets its due, as do the bungling supernatural crime-solvers of Scooby-Doo.

In the next chapter, “Stranger Than Science,” Case reminds the reader that all those fictional stories had an influence on actual news, too. He touches on the Bigfoot and Bermuda Triangle crazes, celebrity psychics and parapsychologists like Ted Serios and Uri Geller, and the 1976 formation of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of the Claims of the Paranormal, whose ranks included Carl Sagan, James Randi, and Isaac Asimov.

Those are the book’s highest points. Like the opening chapters on music and movies, “Devil in the Flesh”—which covers real-life crimes blamed on the occult, as well as religions and cultural movements that were generally harmless but nonetheless incited fear, like the Church of Satan—offers a lot of broad information; this subject could easily fill its own book.

But the final chapter, “World of Wonders,” is particularly notable for its explanation that the occult explosion didn’t end in 1980; that’s just a line of demarcation that Case settled on for purposes of his book. Here, he mentions the Reagan-era Satanic Panic of the McMartin Preschool case (but not, curiously, the later case of the West Memphis Three) and he acknowledges that there’s not one single cause behind the supernatural craze. It was a variety of factors that hit the zeitgeist with uncanny timing:

From different angles it could be viewed as a by-product of the protest generation and the drug culture; or it was a backlash against the supremacy of science; or it was a desperate rearguard response to the decline of mainstream faiths; or it was a show business ploy that caught on with a surprisingly big audience across a surprisingly wide spectrum of formats ... The occult constantly referened, echoed, and overlapped itself. Nothing succeeds like success, and for several years, nothing succeeded like satanic success.

What goes around comes around, it seems. In 2016, you can add white-hot fears like the terrifying political climate and the crumbling environment as contributing factors to the generally apocalyptic vibe of our times. Satanic success is making a comeback, and the release of Here’s to My Sweet Satan couldn’t be more well-timed for those in search of some cultural context. Here’s hoping Case is already working on a follow-up.

Contact the author at cheryl.eddy@io9.com.