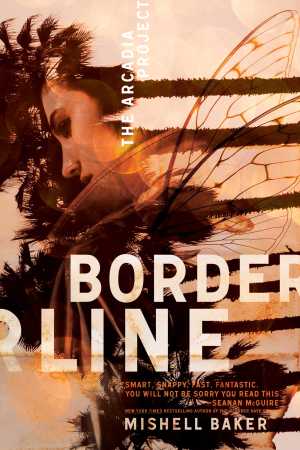

Mishell Baker’s debut urban fantasy Borderline, out now, includes a female character who makes a lot of “unrelatable” choices. Are people finally ready for female characters who are just as edgy as Walter White or Han Solo? Baker has been surprised by people’s reactions.

http://www.amazon.com/Borderline-Arc...

Anti-heroes. They’re brilliant but infuriating. They break the rules. They say what they want without considering others. They have important goals and won’t let anyone stand in their way. And more often than not, they’re men.

The anti-hero has become a dominant character type in the last decade, particularly on TV, which of all media may be the most responsive barometer of public opinion. TV anti-heroes range from the coolly unfeeling (Don Draper on “Mad Men”) to the socially maladjusted (Sherlock Holmes, Dr. House, the other Sherlock Holmes) to the downright murderous (Tony Soprano, Walter White, Dexter Morgan, Frank Underwood, etc.). Viewers forgive and even sympathize with these men, but for much of pop culture’s history the same leeway was not given to women.

When I started writing Borderline, I figured it would be a tough sell. Greg House could get away with limping around making thoughtless wisecracks while solving intractable mysteries, but Millie Roper just seemed to have “too much wrong with her” in ways that beta readers found difficult to articulate. Frustrated, I set the book aside for the better part of a year before I was finally able to find the exact rough edges I needed to file off her to make her acceptable without destroying the core of who she was. But even the softened version of her is difficult to take:

I was only half listening to him; I could still hear Gloria’s raised voice from downstairs, and it twisted my stomach into a knot. I wanted to get away from it, but where was there to go?

“Everybody has a price,” Teo said without looking at me.

“Yeah?” I forced my attention away from the confrontation downstairs. “What’s yours?”

“That depends. For what?”

“Oh, I dunno. An hour in a cheap motel.”

He shot me a look. “With you? Not enough money in the world.”

He said something after that, but I didn’t hear it. It was as though a glass capsule of boiling acid broke inside my head. Before I knew what I was doing, my cane swung in a swift arc and struck the side of Teo’s head.

Audiences often forgive a man for throwing a sucker punch at an ally in a moment of stress, but female leads have not traditionally been allowed to be as abrasive as their male counterparts, let alone violent. Buffy Summers and Sydney Bristow were as tough as any guy on TV, but they were always decent, trustworthy, and loyal to their core group of friends. There has always been an unspoken understanding that the same sort of character-defining pain, rage, and ugliness that make a male character fascinating are unacceptable in a female character because they preclude her from being a safe object of desire. Meanwhile few viewers ever asked if Walter White was desirable; that wasn’t the point.

I was not by far the first to butt heads with this double standard. One memorable trailblazer in TV was actress Katee Sackhoff as Kara Thrace, a.k.a Starbuck, in the reimagined 2004 Battlestar Galactica. During the buildup to the series, Sackhoff was on the receiving end of hostility, boos, and even death threats because she’d dared to reinvent their beloved (male) maverick as a woman. Partially in response to this bullying, Sackhoff dialed the badass factor up to eleven in her performance. Kara drank, smoked, swore, fought her superior officers, cheated on her boyfriend, and worse. In the end audiences adored her for it, proving that a Y chromosome was not, perhaps, a prerequisite to sympathy for a complex and troubled character.

Still, at the time I finished Borderline, I hadn’t yet seen enough deeply messed-up female leads to feel confident that there was any future in what I was writing. But something amazing was already happening, and my agent must have felt it on the wind, because my book found representation in late 2013, right around the same time that the female anti-hero finally exploded.

The rise of new viewing platforms has contributed to the rise of the bad girl, simply by removing the production and distribution bottlenecks that necessitated conservatism in media gatekeepers. Netflix first gave us Orange is the New Black, featuring an entire prison full of flawed, multidimensional women, and then more recently Marvel’s Jessica Jones. Jessica Jones represents the subversion of two tropes—the noir detective and the comic-book superhero—in one deeply conflicted woman. Meanwhile, Amazon’s on-demand distribution did wonders for the popularity of BBC America’s Orphan Black, a show where a single actress explores the variety that can be found in female characters ranging from the uptight soccer mom to the crazed serial killer.

The major networks are starting to get the message as well. In 2015, Taraji Henson won a cartload of awards including a Golden Globe for her portrayal of Loretha “Cookie” Lyon on Fox’s Empire. Just out of prison for drug-dealing, Cookie makes racist comments about one son’s boyfriend and beats the snot out of another son with a broom—and yet still fascinates audiences and makes them root for her as she fights to get back what’s hers.

It’s not surprising, then, that the backlash I was expecting upon the release of Borderline never came. Those of us who write damaged women owe a lot to television, which has both responded to and shaped the taste of a public that consumes many other types of media. It’s up to us to keep these pioneers in mind and bring them up whenever the remnants of the old guard try to tell us what audiences will and won’t accept.

Just like men, women have the right to be ugly. Women have the right to be emotionally unavailable. Women have the right to make terrible decisions. Slowly, audiences are becoming sophisticated enough to understand this. So long as we follow the example of those first male anti-heroes and give our audience something to latch on to - intelligence, humor, suffering, skill, loyalty - a hot mess of a female lead is not an artistic failure. Whether she’s doomed to failure in her own life however... well, that’s for us to know and our audiences to find out.

http://www.amazon.com/Borderline-Arc...