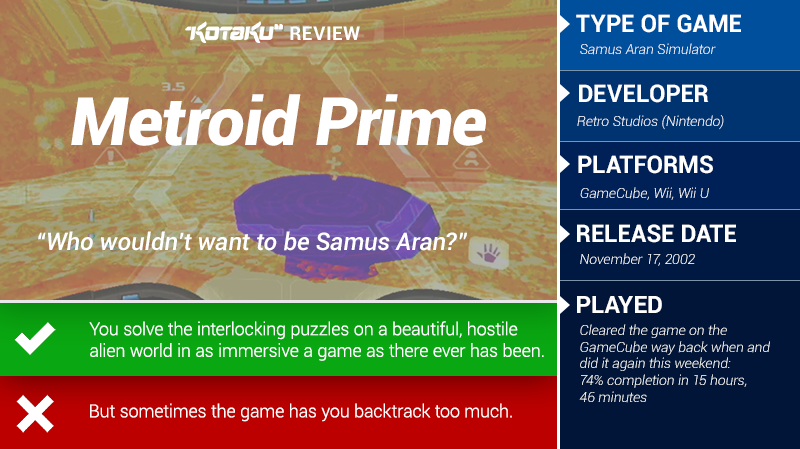

When she shoots, Samus Aran doesn’t miss. That’s one of the fundamental truths of the original Metroid Prime, the first-person sci-fi game that came out on the Nintendo GameCube in 2002. You lock her gun onto a target and fire. She hits it every time.

The game’s designers changed Samus’ aim when they re-released Prime seven years later on the motion-controlled Nintendo Wii. They let you soft-lock Samus’ gun, generally keeping a target in her sights while requiring you to finesse her aim and focus her shots. In other words, they allowed Samus to miss.

Thankfully, you can turn that off, because it’s just not right.

You, dear reader, might be someone who’d fail to brand a shriekbat with a wave beam from 30 yards, but not Samus Aran. And Metroid Prime isn’t a game about players triumphantly being you. It is a game about being the best interstellar bounty hunter and archaeologist in the galaxy.

The first Metroid Prime holds up today in 2016, where you can still play it on a GameCube, a Wii or, as I recently did, on a Wii U running a downloaded copy of Metroid Prime Trilogy. I’ve long considered the game a favorite but hadn’t played it much since release, not until early 2015

When Metroid Prime was first hyped a decade and a half ago, its creators groped for the best term to classify it, eschewing “first-person shooter” for “first-person adventure.” If the phrase hadn’t been taken they could have tried “role-playing game.” Few games before it or since were as effective at letting you embody a role, in this case a woman of few words whose world you see through the visor atop her signature armor.

Her next two Prime adventures are more slickly presented, more complex and maybe–I’ve yet to replay and reassess them–better. But Prime is the originator barely blemished by age of one of the most successful efforts to make a gamer be a game character. The game rarely drags and to an incredible degree still stuns and satisfies.

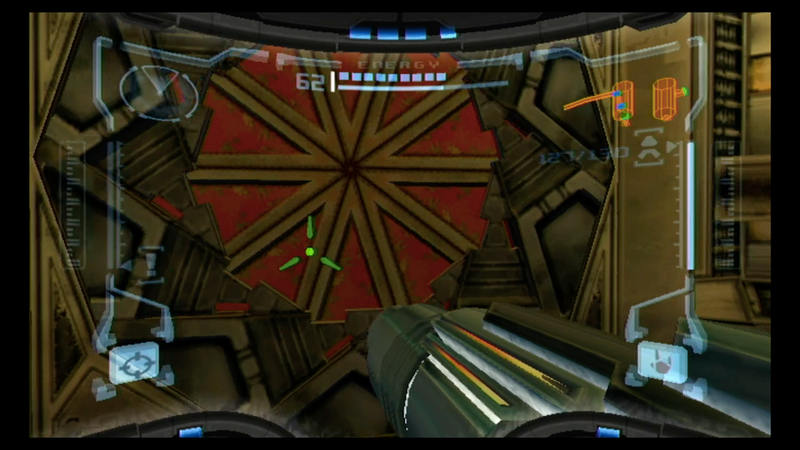

Prime’s presentation of a world seen through a visored helmet was designed for maximum immersion. You aren’t supposed to feel like you are controlling a video game character. You are supposed to feel like you are Samus Aran, and that the things happening to her are happening to you.

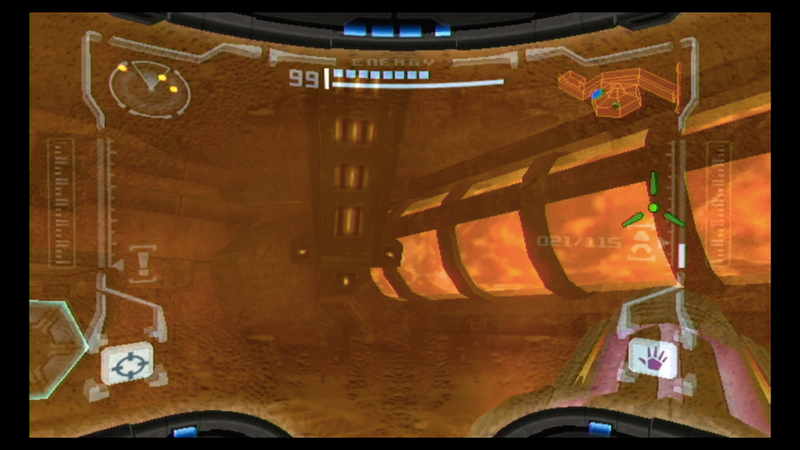

When you explore the lava-filled Magmoor Caverns, jets of steam briefly fog your view.

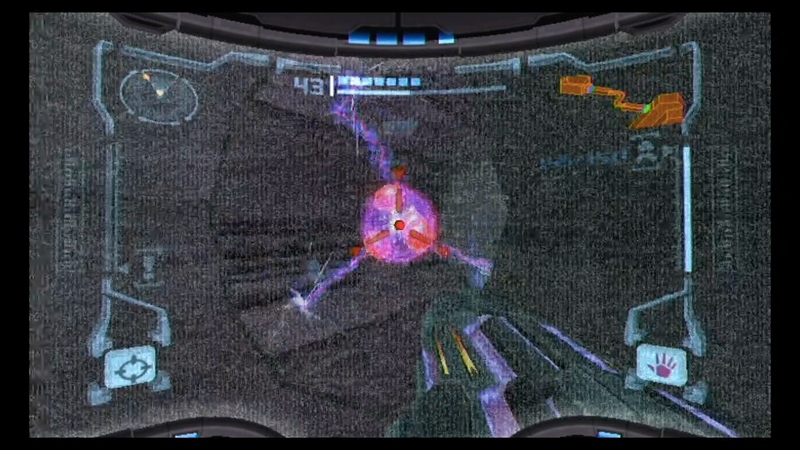

When an electrified enemy attacks you, your display cuts to static.

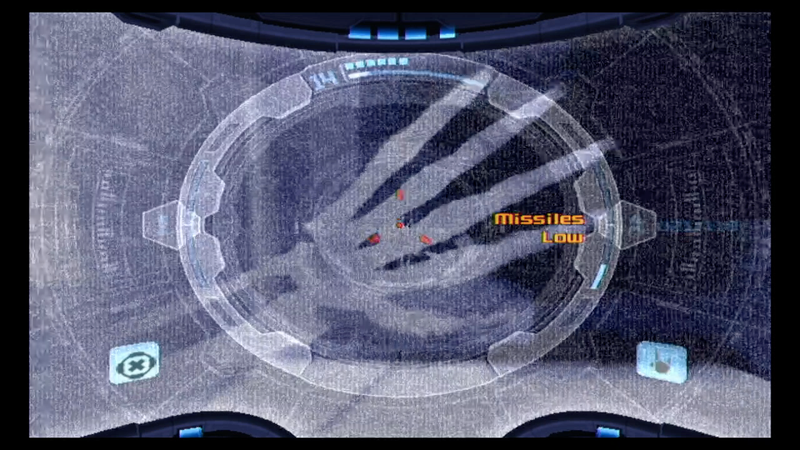

When you finally gain the ability to see the world as one giant X-Ray and reflexively put your/her hand up while getting shot by an enemy, you’ll see her–your–bones.

When light flashes just the right way, you see yourself.

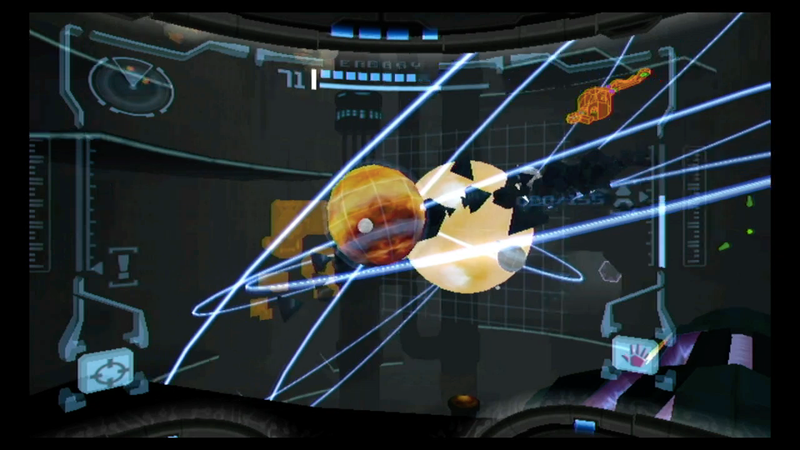

You even eventually see what it’s like to get attacked by a Metroid in first-person:

These would all be mere high-tech parlor tricks if they didn’t serve the purpose of establishing Metroid Prime as the world’s first great Samus Aran Simulator. We are Samus, chasing space pirates and the monster Ridley onto the alien world of Tallon IV, where we will scan flora and fauna to determine what is what. We are Samus, wasting few words as we slowly upgrade our suit so we can see heat signatures, shoot freeze beams and extend a grappling hook made of energy. We have what she’d have: a map, a brain and impeccable aim.

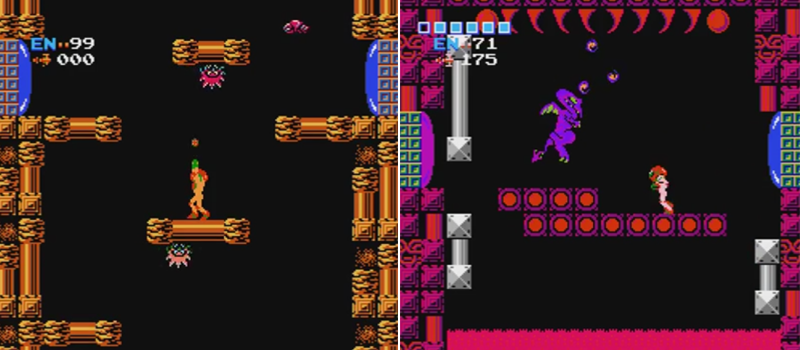

The game starts with a microcosm of what will follow, an effective proof for what in 2002 was a revolutionary idea: that Nintendo’s 2D Metroid games of the 80s and 90s could play as well and maybe better in a first-person mode.

In the 2D adventures, players used Samus to explore caverns and shoot exotic enemies while looking for upgrades that allowed her to reach previously inaccessible areas and defeat previously unbeatable foes. We spent a decent amount of time lost in dark, hostile locations, checking a map to deduce where to go next.

In the prologue, Samus lands on a space station to investigate a distress call. She has a lot of her special abilities already, but the station is quiet. As Samus, the player needs to investigate by exploring ever deeper into the station’s halls and chambers. Soon enough, you’re switching between your scan visor and combat visor, using the former to get text descriptions of the things you’re seeing, the latter to shoot enemy aliens. The action picks up, but the flow is more forensic investigation than gunfight. (The sequel has an even more investigation-oriented intro, establishing an even slower pace for a first-person game, but let’s save that for the Metroid Prime 2: Echoes review.)

The intro sequence is moody and filled with creeping danger. Players might initially and mistakenly think that the developers are going for cinematic seriousness, that they’re chasing the interactive-movie experience that many game makers in that PlayStation-dominated era were going for. The prologue pierces that presumption quickly enough by reintroducing Metroid’s goofiest gimmick, the ability for Samus to roll into a ball.

The morph ball is pure video game, allowing a single button press to change you from Space Indiana Jones to Space Boulder. Like many of Nintendo’s best gameplay ideas, it’s narratively ridiculous but mechanically sound. It lets the developers block a hallway with wreckage but let you roll through an air duct to proceed. Moments of careful walking can turn into rapid rolling.

In terms of Prime’s ongoing Samus simulation, this is key, because Samus Aran is not just an action hero; she’s a puzzle solver. Her world is a series of interlocking puzzles, and her abilities make her into a walking, jumping, ever-upgrading key.

By the time the prologue is over, Samus has bailed from the space station and flown her spaceship down to the planet Tallon IV, where the rest of the game will take place. Stripped of her grappling hook and morph ball transformation, Samus is de-powered and at the bottom of an upgrade latter it’ll take more than a dozen hours to climb. She retains her ability to scan the environment, learn from it, and occasionally shoot stuff, and that is pretty much all she needs.

Armed with a three-dimensional map, you, as Samus, begin exploring. As you do, you hit roadblocks that cause you to imagine the upgrades that will allow you to progress. The unreachable ledge you find near Samus’ landing site will become reachable when you gain the ability to jump higher. Metal doors will need to be blasted; ice must somehow be melted. You can’t always guess correctly, but the game trickles out eurekas as you recognize how a new upgrade you’ve found might interact with something strange you saw earlier. About six hours in, for example, you will gain the ability to magnetize your morph ball. Immediately after that, you realize what all those weird metal strips you’ve been seeing elsewhere in the game are for.

This structure of video game as a generator of successive epiphanies is carried over from the 2D Metroids but feels more marvelous inside a 3D world. Seeing the world from within, the environment slowly loses the claustrophobia of inscrutability and attains the expansiveness of opportunity. More and more of what you observe beyond your visor makes sense. You scan more of it, gain the ability to access more of it, understand the logic of it better and become more comfortable moving through it more quickly and with increased purpose.

Few other games accomplish this epiphany-based design inside a 3D world. It has few imitators, even now. The subsequent games in the trilogy built on its concepts, but few other games do. I consider the recent first-person puzzle game The Witness a worthy if unintentional successor. That game is too frequently compared to Myst even though it better resembles Prime’s great progression of self-empowerment in a beautiful, vexing world through the upgrading of the player’s ability to understand the language of its puzzles.

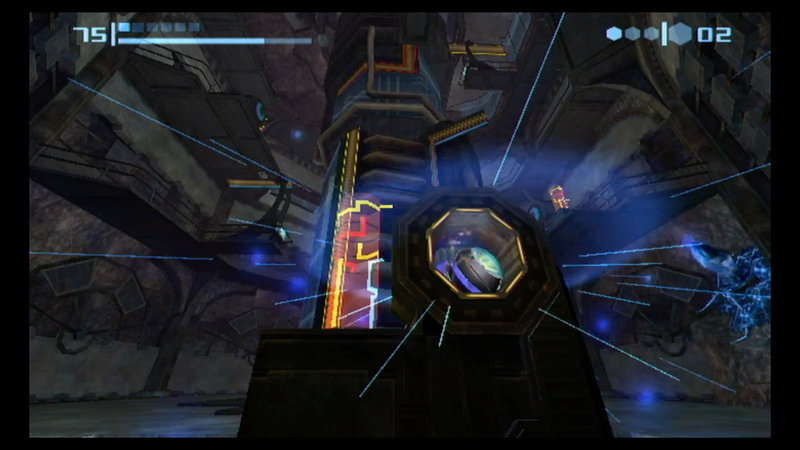

Being Samus Aran in Prime would be a bore if the game’s puzzles were bad and its mysteries were tedious. That’s rarely the case. Prime’s interlocking chambers are masterfully arranged and pleasing to sort out. It helps that the virtual physicality of Samus’ movement through the world feels good. Her jumps, even in first-person, are confident, her morphball-rolling decisively swift. A late-game sequence leading to obtaining the Plasma Beam demonstrates Prime at its best. Players return to a massive room they’ve been through many times before, but now they have the tools to unlock its secrets. Samus, by this time armed with a grapple beam and a magnetic morph ball, can turn what looked like incidental architecture into toeholds for one of the game’s most satisfying climbs.

Metroid prime benefits from being three-dimensional, but it also greatly benefits from being first-person. In retrospect, Metroid needed the deeper transition from 2D series to first-person series that more intimately pulled players in than Nintendo’s Mario and Zelda series needed when evolving from 2D to 3D. The late-90's Super Mario 64 and Ocarina of Time still kept players outside their iconic heroes, still had us controlling them like puppets. That helped us manage the position of Mario’s feet or Link’s item-wielding hands. But it’s what Samus could see that mattered most and so Metroid Prime succeeds in being built around that idea. It uses the perspective that most efficiently lets you see what the hero can see, the better to soak up the most information about her world.

There’s never too much information, either. Shockingly little goes to waste or is presented as mere garnish. This is core to Prime’s art and sound design. Nearly every room looks distinct. Nearly every wall or object has a purpose, be it to hide a secret or suggest something about Tallon IV’s history. The intentionality of Prime’s art is abetted by design so imaginative that area after secret-filled area is still satisfying to look at today .

Samus’ hearing is unexpectedly important, too, also benefitting from the simulation of you being in her head. Many of the game’s rooms contain a low humming sound, an aural hint that there is an extra energy tank or missile upgrade hiding in its walls. You might need to blast a panel with as super missile or use a bomb to blow open a hatch and drain a lake. In an homage to Super Metroid, there’s an elevated glass hallway you’ll pass through multiple times before you figure out you can blow it up and explore the area outside of it. There’s a power-up accessible below, because of course there is.

As you find each hidden power-up, the room it was in stops humming. That leads to a satisfying sense of progressing by making the game quieter. Prime subtly urges players to rid many of its gorgeous rooms of that ugly low hum, that electric sound that interferes with scenic serenity. That feeds back into Samus’ identity as less of a traditional first-person video game destroyer and more of a puzzle-solver and bringer of order. It’s no accident that much of the game’s occasionally-hostile wildlife can just be left alone, especially as Samus becomes more powerful. She isn’t quite a peace-bringer, but she’s also no war-monger.

Prime is at its weakest when sending players from one side of its world to another for an unsatisfying reward. An end-to-end quest to get the Gravity Suit is the low point, though a late-game fetch quest to find a dozen hidden artifacts rivals that. (Correction - 4:27PM: Gravity Suit, not Varia Suit!) The tedium of the latter task can be ameliorated if you are observant enough to find some of the artifacts earlier in the natural course of playing. The knock is that Metroid designers can fall too in love with forcing players to backtrack. The counterpoint is that they can’t produce those epiphanies without backtracking. You won’t feel the excitement of figuring out that the new item you got can open the old barrier that stumped you if you haven’t first encountered the old barrier.

Throughout your adventure, Samus is alone with the wildlife of Tallon IV and a smattering of enemies. You’re just this lady exploring this place, solving its puzzles. You are Samus, but she is also, in a way, you. She’s by herself, trying to make sense of things. Occasionally she’ll grunt as she is knocked back by an enemy shot. She’ll briefly scream if she dies. As you start back up from the last save point, the camera briefly shows her at a distance before swinging around and back into her helmet. Her eyes are yours once more.

To contact the author of this post, write to stephentotilo@kotaku.com or find him on Twitter @stephentotilo.