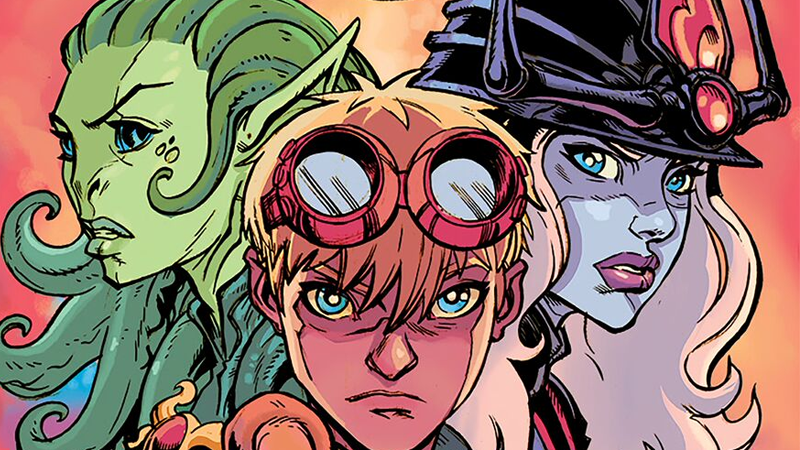

David Gallaher and Steve Ellis’ ongoing scifi webcomic The Only Living Boy follows Erik Farrell, a 12-year-old lost on a strange alien world after he runs away from home. Writing for io9, Gallaher reveals the personal tragedy that inspired Erik’s story—and how being diagnosed with epilepsy transformed the way he wrote comics.

My Winter Beard had gone from “sexy lumberjack” to “backwoods survivalist” in a manner of days. When I used to work a steady office job, my beard was like a giant sweater, it would protect my delicate face from the savage city winds and arctic temperatures. These days, I work from home and have no need for such robust facial follicle-ry. But since the Groundhog predicted an early Spring, I opted to go to the barbershop to rid myself of the beard before it ventured into “sea captain” territory.

The shop I go to is a very traditional, family-owned place that serves a glass of bourbon with every hot towel shave. I walk in, say my hellos, and take a seat. “Shave the beard,” I tell the guy before he even asks. I pause to take off my hat. “And shave everything up top too,” I tell him, pointing to my head. The barber stands silent for a minute. “This scar? How did you get it?”

I hate it.

What do I say about a scar that runs the entire width of my skull? Do I lie? Say something adventurous and clever? Parachute accident? CIA experimenting gone wrong? Do I say nothing? Try and ignore it? Casually, people have come up to me assuming it was a cancer wound.

“My brother has a scar like that, from a landmine,” he confesses.

“Skull surgery,” I relent as I let him take a straight razor to my face.

It wasn’t just a simple skull surgery. Doctors call it “craniosynostosis.” It’s a birth defect that left my head malformed. I had life-saving corrective surgery, but it left me with lifelong scars, developmental delays, and brain damage. It also left me with a seizure disorder—temporal lobe epilepsy—that colors and informs so many of the stories I tell for a living.

Before my epilepsy was diagnosed, I did my best to keep the symptoms secret from other people. My inattentiveness was blamed on daydreaming or ADHD. My nausea was blamed on a spastic colon or food allergies. I’d have to pack spare underwear in my book bag because I never knew when I would accidentally crap my pants or pee myself. To avoid the mocking and the name-calling, I’d do my best to try and cover things up. I was too ashamed to admit that I had no control over my body. I let the shame alienate me from forming any lasting friendships.

As I grew up, I learned how to better bluff my way through blackouts, accidents, or unexplained behavior. I’d stumble my way through schoolwork, get frustrated at my teachers, and get angry at myself for forgetting assignments or spacing out on a test. Administrators would threaten my parents with placing me in Special Ed classes or trying to get me place somewhere else entirely.

But, everybody has a tough time in high school, right? Puberty does strange things to all of us. I did my best to rationalize my inconsistent behavior, but never felt comfortable talking about how it made me feel on the inside.

As an undergraduate, I majored in neurology and education. I became fascinated by authors like Oliver Sacks, who helped put a face on neurological disorders with books like An Anthologist on Mars and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. I took upper-level classes on biopsychology, psychopharmacology, behavior modification, and abnormal psychology. I learned a lot about how the brain worked and even got to cut a few of them open to study the effects of tardive dyskinesia. Classes in education lead me to teach Special Education classes to children with autism, childhood schizophrenia, and disintegrative psychosis. I spent five years teaching before deciding to follow another passion of mine—writing.

“Write what you know,” is the clichéd piece of advice first-time writers get. The truth was I never felt like I knew or understood myself. And I was certainly in no place to write about it. My stomach pains and cramps worsened. Doctors suspected Crohn’s Disease, ulcers, and food allergies. I had intestinal surgery to treat the suspected problem. I had hallucinations, visions, and impulse control problems that I’d attribute to having too much coffee. There’s this mythology that writers are supposed to be a little peculiar or eccentric, but it was all a little too much for me, but I kept on keeping on.

One night, after a date, I passed out. My head smashed up against the window of the Gramercy Dinner. I woke up several days later at NYU Medical Center. Doctors and nurses shaved my head, wired me up to a machine, plugged me into a bunch of monitors, strapped me to a bed, and placed me in the Epilepsy Ward, where I was monitored for over a week for abnormal brain activity. Because of HIPAA laws and hospital regulations, my family, my roommate, and my friends had no idea where I was or what had become of me. I was declared a missing person.

Inside my hospital room, I felt like a missing person. As the Manchurian Candidate played on public television, I found myself filled with delusions and crippling anxiety. What was happening to my body? What was happening to my mind?

When the nurses moved me from the Epilepsy Ward to the Cardiac Ward, I was able to reconnect with my family and friends. Thankfully, most of the wires and straps were gone, but the anxiety was still there. My experiences left me changed.

For the next two weeks, I wrote from my hospital bed. I scribbled down the overwhelming sense of isolation and paranoia I felt. I wrote about the uncertainty. I wrote about the horrible food. The rapid weight-loss. The silent nurses that would parade around my bed during twilight hours. And about the time I flatlined in my room. Those experiences became the foundation of BOX 13—the neo-noir thriller that Steve Ellis and I developed for comiXology.

I entered the hospital on August 1st, 2004; I was released 25 days later. I entered weighing 200 pounds. I left weighing 130 pounds. I came in wearing the clothes on my back, I left with a backpack full of narcotics and pharmaceuticals and a copy of Ender’s Game that was given to me as a gift. I was banned from swimming, video games, driving, alcohol, and coffee. I was given a diagnosis sheet that was 17 pages long. I would have felt broken if it wasn’t for one man, Oliver Sacks, who came to speak with me a few days before I was discharged. I don’t even remember what all we talked about, but he said something nice that stuck with me, “I think you’ll do great things.” Maybe he said that to every patient. Maybe I’m misremembering. All I know is that it made me smile.

Two weeks after I was discharged, I was back in the hospital. Two days after that I was in the hospital. Four days after that I was in the hospital. From August of 2004 to September of 2005, I spent a total 155 days in the hospital. When my epilepsy was at its worst, I was having up to nine seizures a day. I wasn’t expected to see my 30th birthday. Things got very bad for me.

My recovery didn’t happen overnight. It happened over the course of several years. Physical therapy helped with the pain management from the damage the seizures did to my body. Cognitive therapy helped improve my judgment and executive functions. Counseling helped me deal with the emotional challenges I would face trying to adapt to my condition.

The side-effect of multiple traumatic brain injuries was a loss of long-term memories, including nearly all of my childhood memories. While I could remember certain names and landmarks, I had difficulty recalling events surrounding those people and those places.

When it came to continuing my writing career, I found myself making more mistakes, typing slower, and often miscommunicating. I found it difficult to hold multiple ideas in my head at once. I became depressed and heartbroken at how my life had become so disrupted. I wrestled with tremendous physical, emotional, and mental setbacks, some comical… others not so much. It was hard to find any meaning or purpose in life.

Journaling my progress became the beacon to my recovery. I started capturing, through words, the moments when I was memory-less. Without the burden of memories, I found myself enjoying life a little more. My recovery stopped being a slog and became more like a video game, where I’d spend every day leveling up.

A month after a major hospital stint, I found myself well enough to rejoin the working world. I took a position at an advertising firm, where the day-to-day structure facilitated my recovery. As my health recovered, I found myself working hand-in-hand with the New York City Police Department. On my way from the NYPD focus group, I found myself wondering through the film set of I Am Legend. I found myself lost trying to piece together my memories of the story. Was it related to the Vincent Price movie or the Charlton Heston films? As I tried to make sense of my environment, Paul Simon’s “The Only Living Boy in New York” popped up on my iPod.

The song triggered something profound in me. I found myself lost in my imagination, in a world that was equal parts Jungle Book, The Island of Doctor Moreau, and Flash Gordon. A fantastical landscape littered with monsters, exotic locales, and esoteric alien races. And the hero? The Only Living Boy left in the world.

When thinking about Erik Farrell—the protagonist of the series—Steve Ellis and I went back and forth on his age. After a series of conversations, we settled on 12, which we felt would be the right age developmentally for many of the story challenges we had in store for our hero. Being a pre-teen is tough — you’re constantly filled with anxiety about growing up and feel torn between being mature and still being a kid. And when a child experiences something traumatic at this age? It can pull their whole world apart.

Getting deeper into The Only Living Boy we recognized the importance of having a villain, who was riddled with scars of his own. Doctor Once became that character—a medical monstrosity who transforms others into tormented monsters. He’s gnarly in appearance, and plays into our fear of doctors and the scars they leave behind.

When people ask me about my own scar, I try to not dwell. I try not to feel broken. I try not to feel like a monster. People don’t want to hear unpleasant things. So, I deflect, downplay, laugh or squirm my way out of talking about it when I can. I avoid talking about the depression, the frustration, and the anger I have over my own medical condition. When I don’t talk about my scar, these are the things I don’t talk about.

I write about them instead.

The Only Living Boy: Prisoner of the Patchwork Planet will be released in bookstores today. You can read a preview here.

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B01...

David Gallaher is the author of The Only Living Boy and Box 13, and has previously worked on projects writing and editing for Marvel, DC, and Kodansha. Follow him on Twitter on @DavidGallaher.