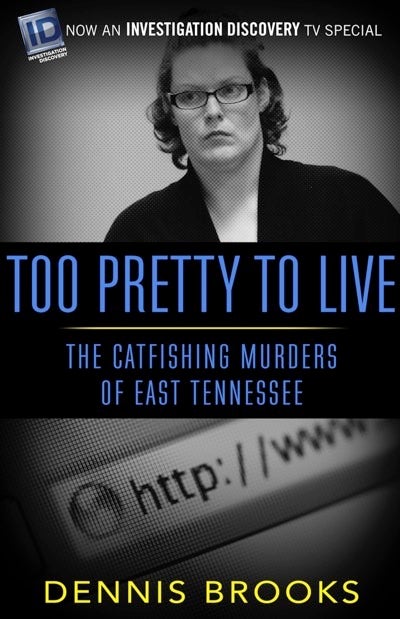

The media scrambled to make sense of this strange, baffling double homicide—the angle that most outlets came up with was “unfriending on Facebook leads to murder!” (Including 20/20, which devoted an episode to the case.) But as prosecutor Dennis Brooks explains in Too Pretty to Live: The Catfishing Murders of East Tennessee, the situation was a lot more complicated than that.

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B01...

The cast of characters include victims Bill Payne and Billie Jean Hayworth, found executed in their own home. The young mother was found still holding her baby, whose life was fortunately spared. The killers were Buddy Potter and Jamie Curd, who had one thing in common: Buddy’s 30-year-old daughter Jenelle, a shut-in whose meek demeanor belied her secret hobby of creating fake online personas—including a CIA agent named “Chris”—who vowed to shield her from all of the enemies she had in her small Tennessee town.

As it happened, Jenelle was also playing the part of her own enemies, writing fake messages from real people, who appeared to threaten her own life. Her grammar was terrible, and her motivations seemingly nothing more than petty jealousy, but she was completely convincing when it counted. Her mother, Barbara, easily fell for the ruse—as did Buddy and Jamie, whose protectiveness toward Buddy’s daughter (and Jamie’s sort-of girlfriend) led them to kill the innocent couple who barely knew Jenelle. And yes, a three-way Facebook unfriending did occur before the killings, but that was just one strand of the web.

This all sounds crazy, because it was, and it’s all true—Brooks’ book is packed full of the poisonous messages that Jenelle crafted, from the safety of her computer keyboard. In a case with no real precedent, Brooks had to navigate his own way, and the tale of the Potters—all of whom received life in prison; Curd cut a plea deal and got 25 years—so haunted him that he had to put it down on the page. Though he confessed he’s “a little Potter-ed out” by now, nearly a year after the final trial, we talked to him about Too Pretty to Live to learn more.

io9: How long did it take you to go through all those emails and Facebook messages to put together what you needed for the case?

Dennis Brooks: I wish I could go back and count all the hours. When you get the messages, they’re not chronological, and there’s no organization to them. It took a lot of going through, and going back, and back again, to really get your arms around it and get a theory about it all. You could see certain things that disturbed you as a prosecutor, but you’ve got to take those threads and weave them into a quilt, so to speak. It took a lot of time.

News reports boiled the killings down to “an unfriending on Facebook led to murder!” But there was a lot more to the case than that. Do you see it as a case of catfishing, of conspiracy, or both? Or is there no way to really simplify a case like this?

Brooks: It’s both. It wasn’t that long before I tried the women in that second trial that it occurred to me that what I had was a catfishing case. Normally, catfishing involves more of a romantic type of tricking of another person. This one was obviously different, because [Jenelle Potter] was manipulating other people into doing her bidding.

And it’s also a strange conspiracy. If I’ve got three people conspiring in a crime, person A, B, and C, the statements between B and C are admissible against A, even though A perhaps doesn’t even know C is in the picture. That’s what the law is, and that was one way for me to get at this catfishing angle. Someone is conspiring with another person, but they don’t know that person is actually their daughter or girlfriend. It makes for an unusual way to prosecute a case. When Charles Manson told his followers to go kill people, they knew it was Charles Manson telling them. In our case, we had someone communicating, but [nobody knew] their actual identity.

To your knowledge, was this the first case of its kind?

Brooks: I’m not aware of another case like this. When I was trying to figure out the forensic linguistics angle, [proving that the emails and messages, signed with different names, were written by the same person]—obviously we’d never used that sort of expert proof in a case before. I did a nationwide search on Westlaw trying to find cases where that kind of proof had been brought in. The only thing I remember finding, criminal-wise, was the Unabomber case. But usually, you’d only find forensic linguistics in like, a contract dispute—something civil. In criminal law, you don’t see it much, at least in reported cases.

Do you think there will be more cases like this going forward—maybe not necessarily on the level of a double homicide, but cases that will require detailed detective work to figure out how what happened online came out in real life?

Brooks: Even in minor cases, you see people coming in with Facebook private messages, where they’re going back and forth. When someone delivers a bombshell in there, there’s always a chance they’re going to say, “Well, I was hacked. I didn’t say that.” Police and prosecutors are going to have to learn how to tell linguistically that someone is who they say they are, or aren’t.

Would this conflict have escalated so much without the influence of social media?

Brooks: Social media didn’t create jealousy. It didn’t invent conspiracy, or motivations to dislike people. But social media facilitated Jenelle’s ability to manipulate people in the way she did. By making up fake messages [that] purported to be from [people who] were threatening to kill her, she was able to take them and show them to people, and try to convince them that she was in danger. Without social media, it’s not possible for her to convince people of that. Plus, with social media, people can just get so absorbed into the online world that I think psychologically we can lose touch with our reality. That was the only form of communication that Jenelle Potter had. Sometimes the internet is a good thing, but sometimes it doesn’t work so well.

Jenelle was very sheltered by her parents, particularly her mother, who was also convicted as part of the murder conspiracy. Who do you think was most at fault?

Brooks: Ultimately, the source of the conflicts with the victims goes back to Jenelle. So that gives her points for being more culpable. But in my opinion, the reasons why Jenelle Potter was the way she was, was because of Barbara Potter not setting limits on her. Jenelle, or “Chris,” would say outrageous, outlandish things, and Barbara’s never taken aback by it. She never expresses alarm or disapproval of even the most harsh language. I think limits are important to a child’s development—without limits, a person’s imagination could go haywire, as it did here.

Obviously the two victims had no idea they were in real danger until it was too late. What about the other people Jenelle had in her sights?

Brooks: I was doing a book signing in Johnson City, Tennessee, and one of the girls, Tara Osborne—who was friends with Billie Jean, and is mentioned in the book—came with her husband. They’d read the book, and afterwards she came up to me and gave me a big hug, saying she never realized how much danger she was in. She never realized how much was percolating against different people. We’re lucky we only had two homicide victims in this case. There was plenty of venom going for other girls that Jenelle Potter didn’t like.