We’re all looking forward to interstellar travel

When Kelly lands at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kashakstan tomorrow night, he’ll have spent 340 consecutive days in space—an American record. That’s about as long as astronauts will have to spend on a spacecraft to travel to Mars and back. Kelly’s graciously-donated body has thus offered NASA an invaluable opportunity to understand what our future Martian explorers will go through along the way. Throughout the one-year mission, a small army of medical researchers has been monitoring Kelly’s bodily functions and comparing the astronaut with his Earth-bound twin brother, retired astronaut Mark Kelly.

In addition to the routine battery of blood tests, physicals, and cognitive assessments, there are two broad questions that Kelly’s mission is uniquely able to help NASA answer. The first one is how the redistribution of bodily fluids in zero-g impacts our health, and chiefly, our vision.

“I like to call this the most complex biomedical investigation ever done on the space station,” John Charles, Chief Scientist at NASA’s Human Research Program told Gizmodo.

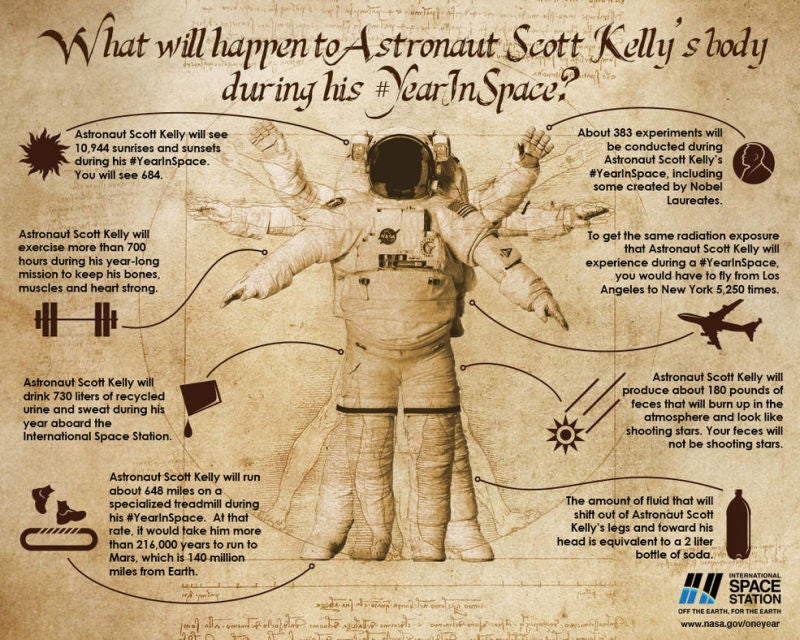

Tethered to the Earth, the force of gravity is constantly pulling our bodily juices down, but in space, everything from our blood and urine to the interstitial fluid surrounding our cells is free to redistribute evenly from head to toe. As NASA points out in the informative graphic below, a two-liter soda bottle’s worth of fluid has shifted out of Scott Kelly’s legs and toward his head during his year in space.

The most obvious effect of fluid redistribution is so-called “moon face”—that puffy-cheeked look that astronauts get after a short period of weightlessness. But there are potentially more sinister effects, including vision deterioration. As former HRP Chief Scientist Mark Shelhamer explained to Gizmodo last fall, astronauts who go to space with perfect vision often come back to Earth slightly nearsighted. NASA thinks this is caused by an increase in the amount of fluid surrounding the brain, which exerts additional pressure on the optic nerve, deforming the astronaut’s eyeballs. But how long the vision impairment lasts, and how bad it can get, are not well understood.

During the Kelly’s mission, NASA’s aptly-named Fluid Shift study has been investigating this using the Russian Chibis suit—a pair of bulky rubber trousers that act like a vacuum cleaner, sucking out air around the wearers’ legs to mimic the effects of gravity. The suit, which has lived on the Russian side of the ISS for years, was built to help cosmonauts re-adjust to gravity before they return to Earth.

Several times throughout the year, Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko have donned the suit and felt the blood drain out of their faces as American and Russian scientists monitored each astronaut’s heart rate, vision, and body fluid distribution. “By restoring normal fluid distribution, we want to see if the eye responds quickly,” Charles told Gizmodo, adding that while “it looks like the experiment did something,” his team needs more time to analyze the data.

Meanwhile, another study is investigating whether the additional radiation in outer space is damaging Kelly’s DNA. This is an issue that we need to worry about a lot when we consider sending people to Mars: all the way, they’ll be exposed to a level of UV radiation hundreds of times greater than the Earth’s surface, as well as even more dangerous cosmic rays.

Exactly how much outer space twists and mutates our DNA is a subject Kelly can help us understand, because he has a twin brother with exactly the same genetic code. “I think the genetic aspect will prove to be one of the important outcomes of this mission,” Charles said.

By comparing Kelly’s DNA with that of his brother, NASA hopes to learn whether an extra-long stint in space leads to any significant changes. These include changes to the Kelly brothers’ telomeres, caps at the ends of our DNA that protect our chromosomes from damage. Our telomeres naturally shorten throughout our lives, resulting in cellular aging. But the stresses of spaceflight may cause them to shorten more quickly, speeding up an astronaut’s biological clock.

The major results from Scott Kelly’s grand experiment are yet to come. But as he prepares to return to terra firma, NASA is already thinking about future One Year missions. Putting a single human in space for a year is a remarkable achievement, but hopefully, more men and women will get to follow in Kelly’s footsteps—growing space lettuce

Follow the author @themadstone