The post-antibiotic future sounds terrifying, but here’s one upside you didn’t imagine: swilling Viking crunk juice to stay alive. New research suggests that mead, the vitality drink of gods and berserkers alike, was a potent medicine in ancient times. And with science, we can make it even better.

Welcome to Gizmodo’s Happy Hour. Substance abuse for nerds.

“A few hundred years ago, people only lived to be 30 or 40 years old,” Tobias Olofsson, a microbiologist at Lund University in Sweden told Gizmodo. “If you had something to prevent infections, you could live much longer.”

Olofsson believes that something was honey wine. His groundbreaking research shows that bacteria found naturally in honey can fight off some of the toughest drug-resistant infections. Now, through his university-backed startup ConCellae, he’s leading an effort to develop a probiotic mead with the same medicinal properties.

The earliest archaeological evidence for mead-making dates back to the 7th century BC in China. But some experts think people have been getting inebriated off honey for far longer. “I personally believe humans have known how to ferment honeys since they left Africa,” Ken Schramm, the mead-maker who wrote the definitive modern guide on honey wine, told Gizmodo. Schramm, along with many archaeologists, speculates that our hunter-gatherer ancestors discovered mead accidentally, when tasting naturally fermented honey in beehives, or by adding honey to rotten fruit as a preservative.

While the origins of mead reman elusive, there’s no doubt our ancestors associated the drink with health and long life. In ancient Greece, mead was the drink of the gods, sent to Earth from the heavens as dew. Odin, the Norse god of healing and battle, was said to have gained his strength by suckling mead from a goat as a baby. And Viking warriors who reached Valhalla would be rewarded with draughts of the stuff, delivered by beautiful maidens. “It was the life-giving liquid across the ancient world,” Schramm said.

But it wasn’t until recently that researchers began asking whether our age-old obsession with mead’s healing properties might have a scientific basis.

That’s where Olofsson’s research comes in. For the last decade, he’s been studying a collection of microorganisms—so-called “lactic acid bacteria,” or LABs—that live inside the honeybee’s crop, a special stomach devoted to nectar collection. These bacteria are a living factory of medicine, exuding a suite of suite of antimicrobial compounds that target and kill pathogens. In 2014, Olofsson published a study showing that honey inoculated with thirteen LABs could treat chronic, antibiotic-resistant wounds in horses. In the lab, the same microbial cocktail eliminates deadly human pathogens, including the notoriously drug-resistant MSRA.

“It was really amazing to discover these bacteria,” he said. “Each one carries special weapons, and together they are very strong.”

But LABs aren’t just found in honeybees—they play a critical role in the maturation of honey itself. “To produce honey from nectar, bees need to lower the water content, which takes two to three days,” Olofsson said. During that time, honeybees regurgitate the nectar, inoculating it over and over with their gut bacteria.“If not for the bacteria, the honey would be spoiled in the hive in just a couple of hours,” Olofsson added.

As honey ripens and its water content drops below 20 percent, sugar and salt become very concentrated, and the LAB can no longer survive. Eventually, the hive is left with mature, sterile honey. But young honey is loaded with LABs—and back in our hunting and gathering days, it’s possible that humans reaped the benefits. “Honey hunters were going out and getting honey from trees that was still at 25 to 30 percent water content,” Olofsson said. “What they were getting is a living medicine.”

What’s more, Olofsson suspects that ancient honey hunters unwittingly made medicinal mead from immature honeycombs. “To get all of the honey out of the wax combs, honey makers would stick them in water,” Olofsson said. “After a day or two of standing, you had an alcoholic beverage.”

A few years back, Olofsson decided to test this hypothesis, by making mead from fresh honey and studying it in the lab. And he discovered something astonishing. “LABs, I found, went from 100 million per gram of honey to 100 billion to a glass of mead,” he said.

A beverage filled with infection-fighting bacteria certainly sounds like a recipe for good health. But we can’t be sure without careful clinical studies. That’s exactly what Olofsson is writing grant proposals to do right now.

“We started learning what kinds of weapons LABs fight with ten years ago,” Olofsson said. “If you can find those substances in the blood when you drink the mead, then we can really confirm that we’ve found the most potent beverage in the world.” Naturally, he’s volunteering himself as the first medicinal mead-drinking guinea pig.

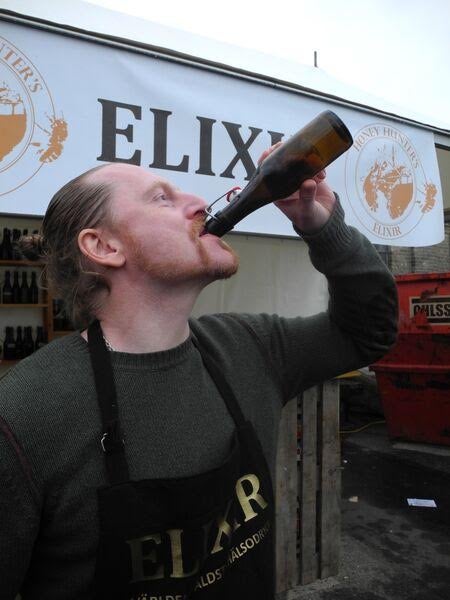

It sounds like a pretty sweet gig. But when do the rest of us get to try this elixir of life? Since the research is still in an early stage, Olofsson says it’ll be a while before probiotic mead hits the shelves. In the meantime, he’s also started brewing a more traditional honey wine, which he hopes to sell in Sweden later this year.

Other mead-makers—most of whom sterilize their product before bottling it—are waiting for the hard evidence before they get too excited about medicinal booze. “It’s tough to say if there could be health benefits at this point,” Schramm said. But he finds the idea intriguing, and is keen to see where the research goes.

And if clinical trials are as successful as Olofsson hopes? Well, he might have really figured out how to bottle Odin’s strength. If that isn’t the pinnacle of scientific achievement, I don’t know what is.

Follow the author @themadstone