Today we bend Clostridium botulinum to our will, forcing it to make our faces smoother and our actors less able to do their jobs. Once, though, people had no idea what caused the “sausage disease.” It took two good men and one bad dinner to let the world know what was going on.

The Sausage Disease and Justinus Kerner

Very old historical accounts of botulism are spotty, in part because very old historical records are spotty and in part because people sickened and died for all kinds of reasons and few people knew one disease from another. Modern researchers believe that some supposed cases of poisoning by belladonna were actually accidental deaths due to botulism, since both dilated the eyes and paralyzed the muscles. No one at the time could distinguish one from the other.

But the lack of formal medical training didn’t prevent people from recognizing patterns. Bans on foods like pork, or pork products like sausage, suggest that people at the time were able to put two and two together and realize that pork products led to death an unacceptable proportion of the time.

The definition of “unacceptable proportion” varied. People struck down by poverty and disaster grabbed food wherever they could. When the Napoleonic Wars devastated Europe, people turned back to pork sausage, even when they didn’t have the time or resources to prepare it properly. In Germany, land of the sausage, deaths skyrocketed and so the earliest of what we would term modern biological scientists turned their focus on the pork disease.

One of these was Justinus Kerner, a man of many talents. He was a medical doctor already known for his romantic poetry—his more famous works include titles like German Forest of Poets and Love’s Agony—and his travel memoirs. Eventually he would become one of the early scientific investigators of psychic phenomena. He settled in the region with a high proportion of poisonings and, in 1817, began a series of articles that proved to be the first clinical description of the symptoms of botulism poisoning. This earned him the decidedly unromantic nickname of “Wurst” Kerner, but he persevered.

He discovered that the poison could develop in sausages even when they weren’t exposed to the air. He learned that it stopped the nervous system from sending necessary signals to the muscles. Although he did not discover the source of “fatty poisoning” or “sausage poisoning,” he came up with a decidedly modern use for it. After experimenting on himself like the mad poet he was, he realized that not all doses of the poison were fatal, or even extremely harmful. Kerner was the first to point out that this poison might be useful for people with conditions like muscle twitches or spasms, allowing them to paralyze the afflicted muscles temporarily to get relief from their symptoms.

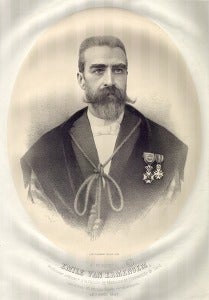

Émile Pierre-Marie van Ermengem and the Very Bad Dinner

In early December of 1895, Antoine Creteur died. He had lived to 87, which was as long a life as anyone could ask for in the 1800s, and he didn’t die of botulism. He wouldn’t have entered this narrative at all if he wasn’t well-liked in Ellezelles, the Belgian town where he had lived. On December 14, after playing at his funeral, the musicians of the Ellezelles brass band gathered at Le Rustic, a local inn, to have dinner together. Thirty-seven people ate smoked and pickled ham. They all got sick. Ten nearly died. Three did die.

This was about seventy years after Kerner’s description of botulism poisoning and everyone knew the symptoms. Scientists were eager to figure out exactly what it was that was causing people to be sick. One of them, Émile van Ermengem, came to Ellezelles to study the ham and the bodies of the dead musicians.

He found something a little like a tiny dark rod, which could grow in a container without air. Van Ermengem grew it in petri dishes and studied it in various foods. He learned that the bacterium made the toxin that affected people rather than being toxic itself. He introduced it to animals and discovered that not all animals had the same susceptibility to it. He studied what happened when it was salted, heated, or passed through digestive juices, and found that salting or heating would stop the process by which the toxin was made, while digestion had very little effect on the toxin.

He named the bacterium Bacillus botulinus. It has since been renamed Clostridium botulinum. It is the bacteria we often hate, but sometimes love, to this day. The discovery didn’t halt the spread of botulism poisoning. There’s always going to be a badly-prepared sausage out there. But these collective men and meals did give people an understanding of what they’re dealing with when they see botulism poisoning, and some ideas about how to use the poison for good.