Amber delivers a slice of ancient life, showing us everything from early predation

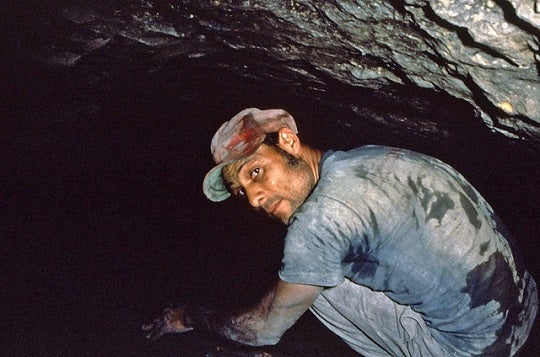

In 1986, Oregon State University entomologist George Poinar went down a mine. It was an amber mine in the Dominican Republic, and he was looking for the bad stuff—the stuff filled with bits of dead insects and other things that wouldn’t look good in a necklace. He found a rich source of that amber—with a little persistence. According to him, “We crawled back about a quarter of a mile to find the vein.”

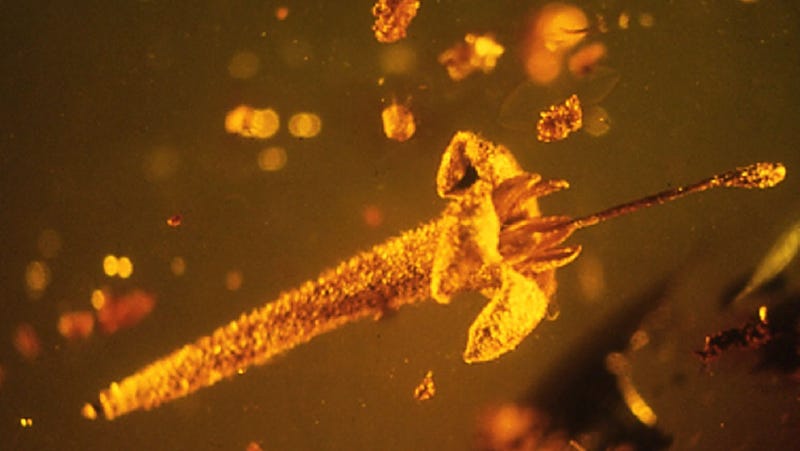

His collection kept him busy for years. It was only recently that he found a tiny relic that was outside of his particular field of expertise. Preserved in the amber was a whole flower. It was at least 15 million years old, undamaged, and extraordinarily lovely.

He had a suspicion of what it was, but to confirm, he needed an expert. He contacted Lena Struwe, a botanist at Rutgers University. Identifying a long-extinct flower requires patience and persistence. She visited two different herbariums—places at which huge collections of flowers are dried and pressed as specimens—to compare modern flowers to the preserved specimen.

We asked her what exactly a botanist looks for in order to classify flowers. She gave us a number of factors, including the number of petals, whether the petals are fused (in which case they form something called a “corolla tube”), the hairiness of the petals, and number and location anthers, where the pollen is actually made.

Struwe explained all the things she saw in the preserved flower that allowed her to match it to its closest living descendant:

At the bottom is the corolla tube (formed from 5 fused petals). Then you have the 5 spreading petal lobes, five pointy anthers in the corolla mouth, and an elongated style coming out of the corolla mouth with a stigma (where the pollen lands) on the apex of the style. There are short hairs on the outside of the corolla.

After finding the flower’s match, Struwe an Poinar were delighted to realize they’d found the oldest example of the Asterid family. Asterids are a family that gives us potatoes, tomatoes, and coffee beans. This particular flower, however, was from the genus Strychnos. Just reading the name should give you an idea of what these flowers are famous for.

Today, the very poisonous plant Strychnos nux-vomica is best known for enlivening mystery novels. Slip a little strychnine into the wine of a cheating wife or a doddering old count with a lot of bickering heirs, and you’ve got yourself a decent Agatha Christie novel. It’s also the stuff that Norman Bates used to kill his mom. Meanwhile, Strychnos toxifera is famous for producing curare. This poison attained worldwide fame in the 1800s. Explorers brought back tales of the chemistry prowess of people in the Orinoco basin, who tipped their arrows with a potent poison that brought down prey without poisoning the meat.

The newly discovered flower, given the name Strychnos electri, was most likely poisonous as well. Poinar speculates that this poison might have preserved it from early herbivores. What could you expect if you were to eat the flower? Both poisons work by disrupting the nerve impulses that govern muscle contractions. Strychnine is the more painful of the two, causing first a sense of agitation and restlessness, then violent muscle spasms (usually manifested as arching of the neck and the back), and then eventual suffocation as the muscles stop working. Curare is easier to endure. It paralyzes the muscles quickly and kills by suffocation.

Alternately, it would also be deadly to eat this ancient plant if only because angry botanists would find out that you ate the oldest example of a flower family and kill you.