Researchers from 21st Century Medicine have developed a new technique to allow long term storage of a near-perfect mammalian brain. It’s a breakthrough that could have serious implications for cryonics, and the futuristic prospect of bringing the frozen dead back to life.

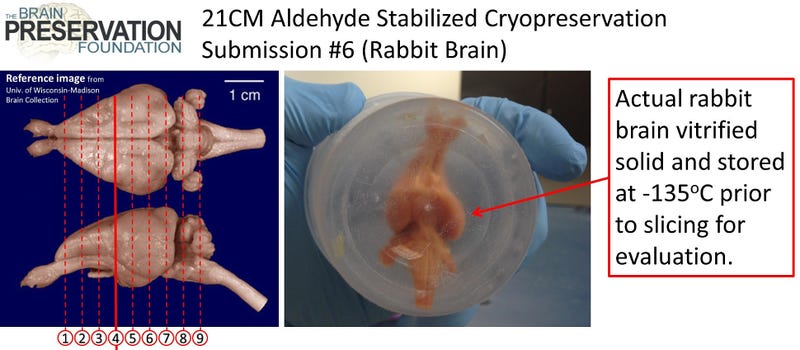

By using a chemical compound to turn a rabbit’s brain into a near glass-like state, and then cooling it to -211 degrees Fahrenheit (-135 degrees Celsius), a research team from California-based 21st Century Medicine (21CM) showed that it’s possible to enable near-perfect, long-term structural preservation of an intact mammalian brain. The achievement has earned not just accolades from the scientific community, but a prestigious award as well; the 21CM researchers are today being awarded the $26,735 Small Mammal Brain Preservation Prize, which is run by the Brain Preservation Foundation (BPF).

The new technique means that neuroscientists will now be able to study brains, both animal and human, in unprecedented detail. But it could also apply to cryonics —the practice of preserving a person in cold storage in the hopes that they’ll eventually be brought back to life once the requisite technologies exist.

Brains don’t fare well during the cooling down process, even when advanced cryopreservants are used to protect the brain from freeze damage. This limitation has made it difficult for scientists to properly preserve and study the brain and its detailed web of connections following death. Reversible cryopreservation—that holy grail of cryonics—has so far remained out of reach.

To change that, the BPF launched two contests back in 2010, one for successfully demonstrating the reliable long term preservation of a small mammal’s brain, and a similar prize for doing the same in a large mammal (the Large Mammal Brain Preservation Prize). To win either, a research team had to demonstrate that the ultrastructure of a mammalian brain—including the animal’s entire connectome and synaptic structure—can be reliably preserved indefinitely after death.

“Fortunately this work has been successful, as we have been able to validate the small mammal protocol, and are now working on evaluating the large mammal protocol,” noted BPF vice-president and co-founder John Smart in an email to Gizmodo.

The 21st Century Medicine team, led by cryobiologist Robert McIntyre, discovered a way to preserve the fragile neural circuits of an intact rabbit brain using a glutaraldehyde-based fixative along with with cryogenic cooling. The details of this procedure, called Aldehyde-Stabilized Cryopreservation (ASC), can now be found in the journal Cryobiology. The new protocol was verified independently by neuroscientist and BPF president Dr. Kenneth Hayworth and Princeton University neuroscientist Dr. Sebastian Seung.

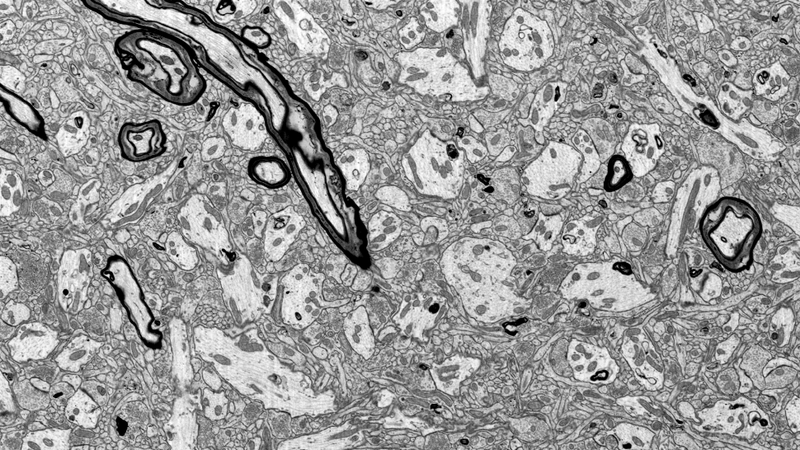

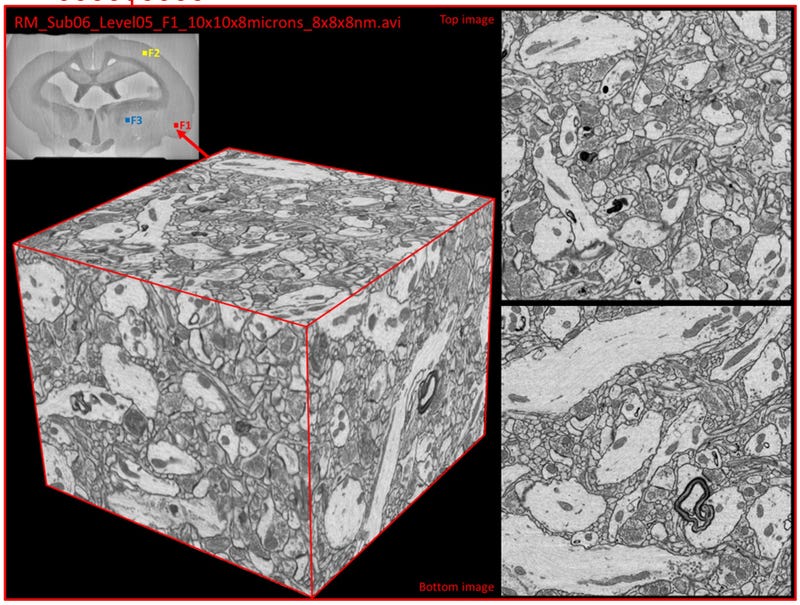

“Every neuron and synapse looks beautifully preserved across the entire brain,” noted Hayworth in a press statement. “Simply amazing given that I held in my hand this very same brain when it was frozen solid...This is not your father’s cryonics.”

As an idea, cryonics has been around for decades. Back in the 1960s, futurist Robert Ettinger speculated that deceased individuals may eventually be revived after prolonged storage in vats of liquid nitrogen. Half a century later, cryobiologists are still struggling to preserve dead individuals, let alone bring them back to life. As already noted, reversible cryopreservation has proven difficult owing to the intense damage inflicted on brains during preservation—things like fractures and damage to cell membranes.

This fundamental limitation has inspired a new generation of cryobiologists, who are focused on techniques that preserve the delicate pattern of synaptic connections, known as the “connectome,” that encodes a person’s memory and identity. Called plastination or chemopreservation, the new approach involves chemical fixation and the embedding of brain tissue in a plastic-like form for long-term storage. McIntyre’s system is unique in that it combines chemical fixation with cryonics.

http://io9.gizmodo.com/5943304/how-to...

But unlike conventional cryonics, which attempts to preserve the biological components of a person’s body or brain, this new school of cryobiology envisions “synthetic revival”—a process in which the complete database of a single individual’s neurological information can be used to create a new digital version. The revived digital brain, also known as a whole brain emulation, could be uploaded into a computer simulation or robotic body. But because the system involves destructive scanning, the biological components of the original brain would be destroyed by the toxic chemical bath during the preservation process. Following preservation and stabilization, these brains would be cut into extremely fine slices, and then individually scanned. Together, the collection of digitized brain slices would represent an uninstantiated individual.

This idea fits with recent evidence suggesting that long-term memories are not altered by the preservation process. And indeed, the latest research suggests that memories and personal identity are physically encoded in the brain. Scientists recently demonstrated that it’s possible to target and erase memories in mice, while also “incepting,” or introducing, episodic hippocampal and cortical memories into mice via optogenetic alteration of individual neurons. “This important work [and others] tells us more than we’ve ever known before about the specific cellular and molecular processes by which memories are made and stored in mammalian brains,” Smart said.

The trick is to capture this neurological information at the sufficient level of resolution, and then store it for future use. To pull that off, McIntyre perfused a rabbit’s vascular system with a chemical fixative called glutaraldehyde. This quickly stopped metabolic decay and fixed the proteins in place. Once stabilized, the tissue and vasculature was brought down to an optimal temperature. The researchers added cryoprotectant slowly over four hours to avoid damaging the brain’s structure. Normally, a brain starts to degrade after just 30 minutes following death. But as McIntyre explained to Gizmodo, the “glutaraldehyde [bought] us weeks and the cryoprotectant [bought] us centuries.” The resulting brain was fixed and frozen—both literally and figuratively—such that its synaptic elements remained intact.

McIntyre likened the process to preserving a book.

“If brains are like books, ASC is like soaking a book in crystal-clear epoxy resin and hardening it into a solid block of plastic,” he explained. “You’re never going to open the book again, but if you can prove that the epoxy doesn’t dissolve the ink the book is written with, you can demonstrate that all the words in the book must still be there, preserved in the epoxy block like a fly in amber.”

If someone wanted to restore the contents of the book, McIntyre said they could carefully slice it apart, digitally scan all the pages, and then print and rebind a new book with the same words. But that’s only possible if the data is still intact, unaffected by the preservation process. Think of the brain’s connectome as the words on the pages of a book.

“Overall, I think it is a neat step forward,” explained Oxford University computational neuroscientist Anders Sandberg. “Not a giant leap for mankind, but one of those useful things you need to do the eventual giant leaps.”

In terms of cryonics and the prospect of whole brain emulation, Sandberg said it improves the overall outlook—at least if one believes that scanning and emulation is the way to go. But not everyone is convinced that destructive scanning is the right approach, or if cryonic techniques in any manifestation will ever work.

“To a functionalist like me, this is good news,” he said. “But I know people who hold the body-identity view of personal identity

http://io9.gizmodo.com/you-ll-probabl...

It remains to be seen how this new approach to brain preservation will affect the cryonics community as a whole. Classicists at Alcor and the Cryonics Institute steadfastly believe that brains (and bodies, for that matter) must be preserved with as little damage as possible. But the “plastinators,” as the new breed is called, believe it’s important to preserve the information embedded in the brain, while placing a low premium on preserved biological parts. As Sandberg pointed out to Gizmodo, a degree of tension is now emerging between the proponents of these two approaches, as witnessed by this tongue-in-cheek slide prepared by Greg Fahy of 21st Century Medicine.

When asked which of the two techniques he would use for himself, Sandberg pointed out that AMC has not been proven on larger brains, and that he’d rather use a method predicated on reviving tissue “just in case.” But given the recent improvements in fine structure and preservation, he said he may shift to this method once it’s been demonstrated in human brains.

McIntyre agrees, and said the technique needs to be discussed more before it can be considered in cryonics. “It needs to be much more extensively tested and made robust in a research setting,” he said. “A big claim like this needs a lot of evidence to support it.”

[Cryobiology, Brain Preservation Foundation]

Top image: Electron microscope zooming through a brain slice. All images via 21st Century Medicine/Brain Preservation Foundation.