The conspiracy theory-laden social media onslaught unleashed by rapper B.o.B.

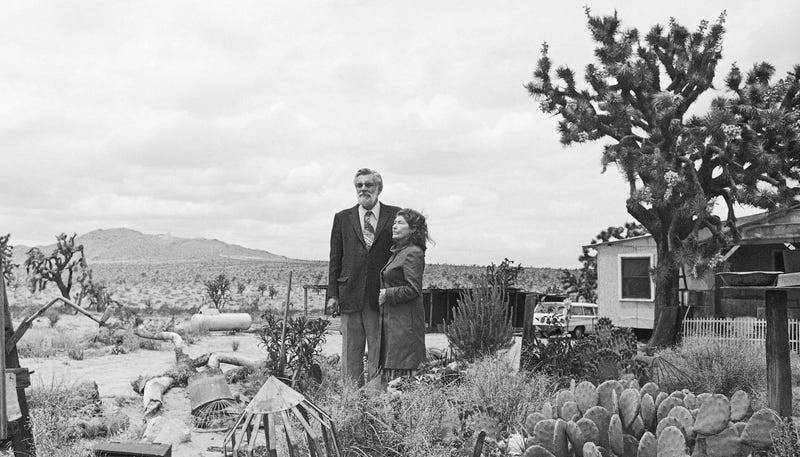

Charles Kenneth Johnson was born in 1924. He became president of the International Flat Earth Society in 1972—but he’d believed the Earth was a flat planet since he was a child growing up in Texas and couldn’t wrap his head around the concept of gravity. He kept those beliefs with him during his 25 years working as an airplane mechanic in San Francisco. Eventually, he moved to the Mojave Desert and made a career shift into activism. He took over running the Society when its previous leader, Johnson’s good friend Samuel Shenton, passed away and designated him as successor. Shenton had founded the group in the 1950s but traced its origins back to 19th century England.

That Johnson’s desert abode was so close to Edwards Air Force Base, home of NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center, only made it more curious how strongly Johnson stuck to his beliefs. He believed the space program was a full-on hoax. In 1980, he gave an interview to Science Digest in which he opined “You can’t orbit a flat earth. The Space Shuttle is a joke—and a very ludicrous joke.”

Though he hadn’t achieved more than a high-school education, Johnson was a well-spoken, passionate advocate whose fame even landed him an ice cream commercial. Thanks to his promotional efforts through regular newsletters (tagline: “Restoring the World to Sanity”) on topics such as “Charles Lindbergh Proved Earth Flat,” he grew the Society’s membership from a handful of believers to some 3,000 strong.

After he died in 2001, his New York Times obituary offered certain admiration for a life spent so dedicated to his cause:

Mr. Johnson, who called himself the last iconoclast, regarded scientists as witch doctors pulling off a gigantic hoax so as to replace religion with science. He based his own ideas on the Old Testament references to a flat earth and the New Testament saying that Jesus ascended into heaven.

‘’If earth were a ball spinning in space, there would be no up or down,’’ he told Newsweek magazine in 1984.

His essential suggestion was that people should just look around and trust their own eyes. ‘’Reasonable, intelligent people have always recognized that the earth is flat,’’ he said.

In quarterly newsletters, Mr. Johnson seemed to have an answer for almost everything. Sunrises and sunsets? An optical illusion. The moon landing? An elaborate hoax with a script by the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, staged in a hangar in Arizona. (And Mr. Johnson was not alone; a Washington Post poll in 1994 found that 9 percent of Americans thought the landing was faked.)

Eclipses of the sun? ‘’We really don’t have to go into all that,’’ he told The New York Times in 1979. ‘’The Bible tells us the heavens are a mystery.’’

In 1995, Johnson and his wife Marjory (“who believed in a flat earth because she did not hang from her toes in her native Australia”) lost their home in a terrible fire; it destroyed all of the Society’s archives. Marjory died in 1996; when Johnson died five years later, the group had dwindled to very few members. But thanks to the internet, the Flat Earth Society lives on. Its website, which has a PDF library of Johnson’s original newsletters as well as an online forum, notes that it officially started accepting new members in October 2009.

In 2010, its American-born but England-based new president, Daniel Shenton, gave an interview to the Guardian in which he spoke about keeping Johnson’s message alive in the 21st century. Unlike his predecessors, he believes in global warming and evolution. But the shape of the Earth ... not so much:

The Earth is flat, he argues, because it appears flat. The sun and moon are spherical, but much smaller than mainstream science says, and they rotate around a plane of the Earth, because they appear to do so.

Inevitably, Shenton’s argument forces him down all kinds of logical blind alleys – the non-existence of gravity, and his argument that most space exploration, and so the moon landings, are faked. But, while many flat Earthers have problems with the idea of orbiting satellites, Shenton navigates the London streets using GPS. He was also happy to fly from the US to Britain, but says an aircraft that flew over the Antarctic barrier would drop from the sky, and from the planet.

Interestingly, unlike Johnson, Shenton spent most of his life believing the Earth was round but “began asking questions after hearing musician Thomas Dolby’s 1984 album The Flat Earth;” subsequent research into the Flat Earth Society turned him into a believer. As of 2014, the group was still keepin’ on, and has an active Twitter account, retweeting articles about the cause and spreading holiday cheer to its followers:

Top image: Charles K. Johnson, left,, and his wife, Marjory, are shown outside their home near Lancaster, Calif. (AP Photo/RG)