The release of Star Wars in 1977 was an absolute gamechanger, on so many levels—from effects, to toys

In the mid-1970s, Marvel was in trouble. After its success in the ‘60s, creating hits like Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, and countless others, Marvel had grown too quickly, too fast. General sales of comics across the industry were down, and something was about to give.

At the same time, Star Wars was a film that seemingly no one believed in, including Marvel. When George Lucas was first shopping around potential novelizations and comic adaptations of his upcoming movie in 1975, publisher Stan Lee was adamant that scifi comics sold poorly, as did licensed comics. When the industry was already hurting, why take a risk on this unknown movie?

But despite Lee’s rejection, not everyone at Marvel agreed with him. Roy Thomas, who had briefly been Editor-in-Chief of Marvel in the early ‘70s was put into contact with Charles Lippincott, George Lucas’ advertising publicity supervisor in the run up to Star Wars. Over several meetings with Lucas and Lippincott, Thomas was slowly convinced to give the movie another chance at Marvel. He returned to the company and re-pitched the adaptation, and Lee relented. In April 1977, two months before the film came out, Star Wars #1—written by Roy Thomas, and with art by Howard Chaykin and Thomas Palmer—went onto shelves, promising an adaptation of “The Greatest Space Fantasy Film Of All.”

Common, romanticized consensus is that Star Wars came out of nowhere when it was released, but the savvy work of Lippincott in the year prior to the film’s opening had actually created a growing, eager audience for the film, through a tour of the convention circuit in 1976 to drum up interest. By the time Star Wars #1 came out, there was a hungry fanbase wracked with anticipation that voraciously consumed the comic in numbers well beyond anything Marvel had expected. After Star Wars the movie actually came out, the only real way to re-experience it was to return to the theater or buy the novelization or comics, it skyrocketed to the top of Marvel’s sales list. The first few issues were reprinted again and again, then collected in bundles, and people lapped it up—not just in the U.S., but around the world.

Han Solo meets “Jabba” in Star Wars #1. Without the movie to go on—Jabba would eventually be excised from the first film due to a lack of time to finish designing the Hutt’s appearance—Chaykin had to turn the mobster into a random alien creature from the background of the Cantina sequence.

Star Wars mania had gripped the planet, and Marvel sold almost two million comics within the first year of release alone. Star Wars had defied everyone’s expectations in the comics industry, and for Marvel especially, it was a solid seller at a time when they needed it the most.

But after the successful start, the Star Wars comic found itself in a strange place—there was no more Star Wars to adapt. Only the first six issues covered the events of the movie. At the time, Lucas cared little about what happened outside of his films; with nothing else to go on, Marvel desperately needed their own material. Star Wars had left its heroes (or as Marvel affectionately called them on many a cover, the “Star Warriors”) in a hopeful place, but where could they go next? They couldn’t beat the Empire, because that story was saved for the movies. They couldn’t face off against Darth Vader over and over, either. So Marvel concocted its own stories.

The company turned to the roguish background of Han Solo for refuge, starting with “Eight Against a World!” in Star Wars #8. It was an adventure all about the smugglers and scoundrels of the world that Han had called his former allies before joining the Rebellion, as he rejoined them to fight space pirates. One of these smugglers in particular actually managed to draw the ire of Lucas: Jaxxon, a smooth-talking humanoid neon green rabbit created by Thomas and Chaykin who did martial arts and dressed like a Flash Gordon extra. Lucas, through Lippincott, raged at the character’s existence, and Jaxxon was rapidly phased out.

It was then Thomas realized that until the sequel came out, Star Wars would be in a creative quagmire, and quit the book. Chaykin followed shortly after, and the pair were replaced by Archie Goodwin and Carmine Infantino. Over the next few years, the Star Wars comic had to wax and wane between adapting a new movie and telling original stories as the Rebels dodged the Empire (and thus the surrounding elements of the movies) and fought one-off aliens, rogue Imperial Barons and bounty hunters.

Mary Jo Duffy took over as writer in January of 1983, shortly before the release of Return of the Jedi in theaters. With the (apparent) end of the movies—and without the watchful eye of Lucasfilm, or any other expanded universe material to adhere to—Duffy essentially had the keys to the galaxy far, far, away. It would be Marvel that first got to answer a question being revealed by The Force Awakens: What’s next for the Rebel Alliance after they’ve saved the galaxy?

Leia and Han turned into diplomats, having to convince worlds and star systems that the Alliance could govern effectively and be different from the Empire. Luke dove into deeper studies of the Force, and struggled with training new Jedi and the fear of falling to the Dark Side like his Father did. New threats arose in the wake of the Empire’s fall, like the sinister alien Nagai, or Lumiya, a female Sith who wielded a bizarre “light-whip” in combat. Duffy and artist Cynthia Martin’s set up would ultimately inspire the world picked up on by the official Expanded Universe in the 1990s—Lumiya herself was brought along, as were many of the elements the writers created—and even some of the elements discussed about The Force Awakens.

But without movies, Star Wars couldn’t survive. Ewoks and Droids cartoons failed to ignite new interest; Kenner wrapped up toy production after years of market dominance; and as sales gradually decreased over Duffy’s tenure, Marvel canceled the series in 1986, after 107 issues—as did, seemingly, the franchise itself.

But not for long. Lucas began teasing a desire to make more Star Wars movies, and at Lucasfilm, there was already a discussion

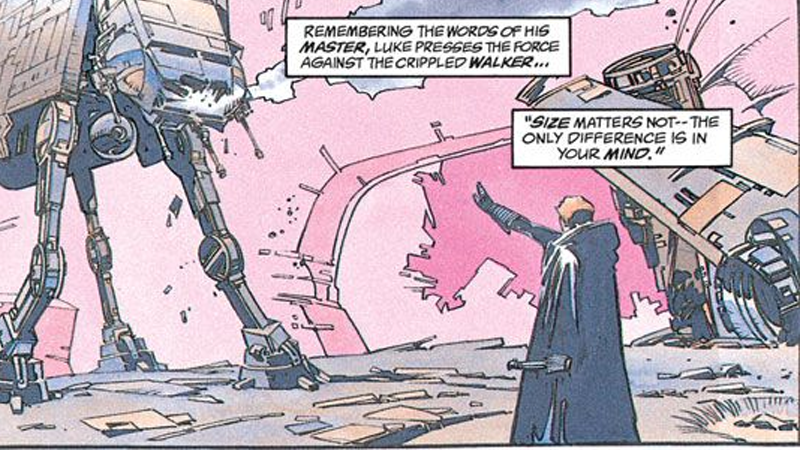

An all-powerful Luke Skywalker downs an AT-AT in Dark Empire #1.

Much to some Star Wars fans’ chagrin, Dark Horse would ultimately lose the rights

The Marvel Star Wars returned to was much different to the one it landed at in 1977. This one was no longer in danger (after some close calls over the years), but one of the most powerful comics publishers in the industry. The only thing that didn’t really change? Sales power. Since Star Wars #1 released in January of this year, the series and its spinoffs—Darth Vader, Princess Leia, Shattered Empire (a precursor to The Force Awakens itself), and more—have crushed sales records, and are considered some of the best comics of the year.

It was a long way round, but Star Wars and Marvel were together again—forging a new path into a galaxy we all loved, as it did so all the way back in 1977.