A monthlong Gizmodo investigation has uncovered compelling and perplexing new evidence in the search for Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous creator of Bitcoin. According to a cache of documents provided to Gizmodo which were corroborated in interviews, Craig Steven Wright, an Australian businessman based in Sydney, and Dave Kleiman, an American computer forensics expert who died in 2013, were involved in the development of the digital currency.

Wired reported this afternoon that Wright and Kleiman were likely involved in creating Bitcoin. Gizmodo has been following a similar trail for weeks, one that in recent days has included face-to-face confrontations with Wright’s business partners in Sydney and interviews with Kleiman’s closest associates in Palm Beach County, Florida. Gizmodo also obtained confirmation from on-the-record sources that Wright claimed on at least two occasions that he and Kleiman were both involved in the creation of Bitcoin.

In early November 2015, Gizmodo received a series of anonymous tip emails from someone who claimed to not only know the true identity of Satoshi Nakamoto, but who also claimed to have worked for him. “I hacked Satoshi Naklamoto [sic],” the first message read. “These files are all from his business account. The person is Dr Craig Wright.” What followed was a package of email files apparently pulled directly from an Outlook account belonging to Craig Wright, an Australian academic, computer engineering expert, and serial entrepreneur with a litany of degrees and corporations to his name.

Last year, Wright publicly announced his plan to establish the “world’s first Bitcoin bank.” Wright’s LinkedIn page lists him as the CEO of DeMorgan Ltd, a company whose website describes it as “focused on alternative currency, next generation banking and reputational and educational products with a focus on security and creating a simple user experience.” Among DeMorgan’s subsidiaries, also listed on its website, are C01n, a Bitcoin wallet company; Coin-Exch, a Bitcoin exchange; and Denariuz, the aforementioned Bitcoin bank, and one of the top supercomputers in the world.

Several of the emails and documents sent to Gizmodo point to a close relationship between Wright and Kleiman, a U.S. Army veteran who lived in Palm Beach County, Florida. Kleiman was confined to a wheelchair after a motorcycle accident in 1995, and became a reclusive computer forensics obsessive thereafter. He died broke and in squalor, after suffering from infected bedsores. His body was found decomposing and surrounded by empty alcohol bottles and a loaded handgun. Bloody feces was tracked along the floor, and a bullet hole was found in his mattress, though no spent shell casings were found on the scene. But documents shared with Gizmodo suggest that Kleiman may have possessed a Bitcoin trust worth hundreds of millions of dollars, and seemed to be deeply involved with the currency and Wright’s plans. “Craig, I think you’re mad and this is risky,” Kleiman writes in one 2011 email to Wright. “But I believe in what we are trying to do.”

Writing about Satoshi Nakamoto, the Bitcoin originator’s pseudonym, is a treacherous exercise. Publications like the New York Times, Fast Company, and the New Yorker have taken unsuccessful stabs at Satoshi’s identity. In every instance, the evidence either hasn’t added up or those implicated have issued public denials. And then there was Newsweek, whose 2014 story “The Face Behind Bitcoin” is easily the most disastrous attempt at revealing the identity of Satoshi. The magazine identified a modest California engineer, whose birth name was Satoshi Nakamoto but who went by Dorian, as the creator of Bitcoin. The story resulted in a worldwide media frenzy, a car chase, and—after Dorian’s repeated denials and legal threats—a great deal of embarrassment for Newsweek.

All of which means that the real Satoshi Nakamoto is still out there. And although Bitcoin has yet to upset the free market and establish the crypto-libertarian monetary utopia that its boosters once anticipated, the currency doesn’t appear to be going away: its users span the globe, with some analysts predicting 5 million worldwide by 2019. Bitcoin isn’t just some cryptographic niche. It’s an outrageous, brilliant phenomenon concocted by either a single subversive genius or a group of them. The digital currency went from being worth fractions of a penny in 2009 to $1,200 per coin just four years later, built on a network that makes wiring money anywhere as simple as sending an email, and that aims to singlehandedly render the entire global financial system obsolete. If Satoshi Nakamoto revealed himself to the world, he (or they) would be lauded as one of the greatest living minds of computer science—and the target of incessant, global scrutiny.

Craig Wright is not modest. On the website of Panopticrypt, one of his many companies, Wright describes himself as “certifiably the world’s foremost IT security expert.” In a May 2013 blog post titled “Morning Manifesto,” Craig proclaims to himself and the world:

I will make a solution to problems you have not even thought of and I will do it without YOUR or any state’s permission! I will create things that make your ideas fail as I will not refuse to stop producing. I will not live off or accept welfare and I will not offer you violence. You will have to use violence against me to make me stop however.

And at an October 2015 panel discussion with fellow Bitcoin experts (including Nick Szabo, long suspected by many as being the real Satoshi), Wright is asked to introduce himself. “[I do] a whole lot of things that people don’t realize is possible yet,” he replied. When asked by the moderator for clarification, Wright said that “I’m a bit of everything...I have a masters of law...I have a masters in statistics, a couple doctorates, I forget actually what I’ve got these days.” When asked how he got involved in Bitcoin, Wright pauses before replying: “uhh, I’ve been involved in all of this for a long time...I try and stay...I keep my head down.”

That’s all circumstantial evidence. But the hacked emails and other documents, if authentic, show Wright making repeated claims to being Satoshi Nakamoto over a period of years starting in 2008, before Nakamoto published the now-legendary white paper introducing the world to Bitcoin.

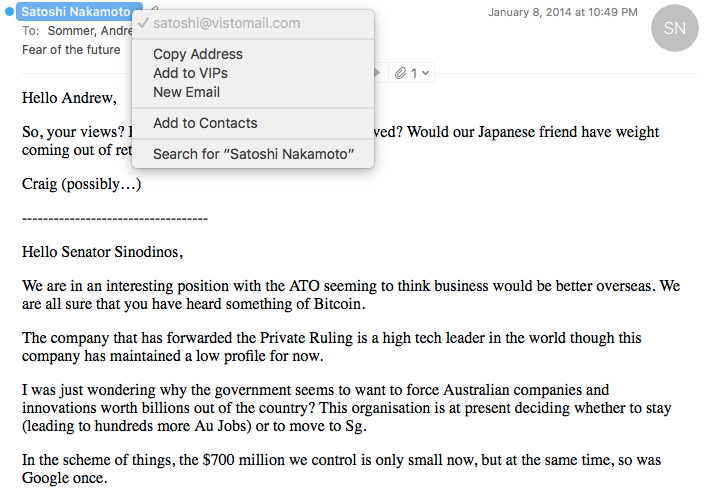

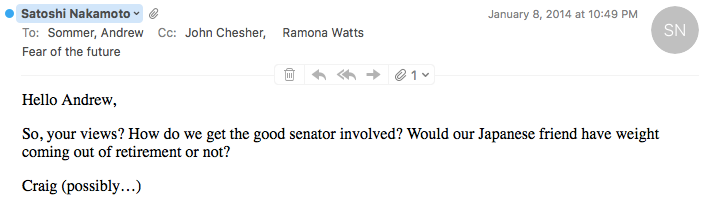

The most persuasive evidence from the apparently hacked account is a message dated January 8th, 2014, which shows Wright emailing three colleagues from satoshi@vistomail.com, the email address that Nakomoto used to regularly communicate with early Bitcoin users and developers. In this thread, with the subject line “Fear of the future,” Satoshi@vistomail.com strategized about lobbying Australian Senator Arthur Sinodinos on the matter of Bitcoin regulation:

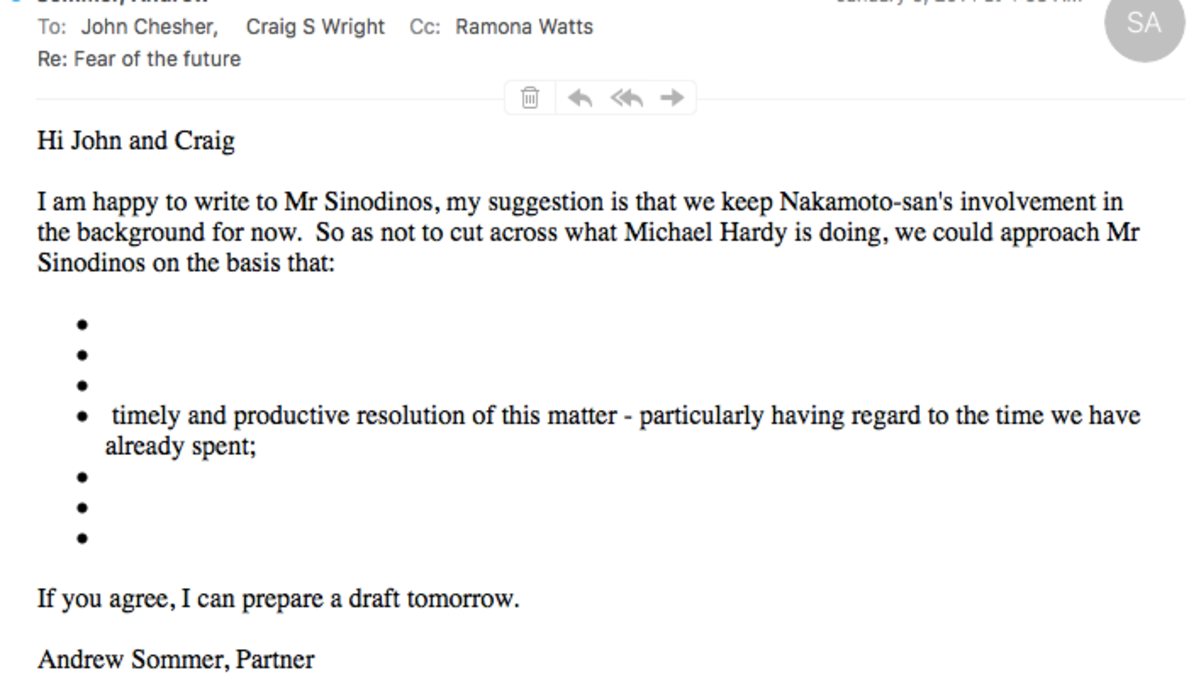

The email includes a signature with the name Satoshi Nakamoto and a phone number that belongs to Craig Wright. The reply-to field, which determines where responses to the message will be sent, lists an email address that, according to Google, belongs to Craig Wright. Also included in the cache of messages is this reply from Andrew Sommer, a partner at Sydney-based law firm Clayton Utz, which represented Wright at the time the emails were exchanged:

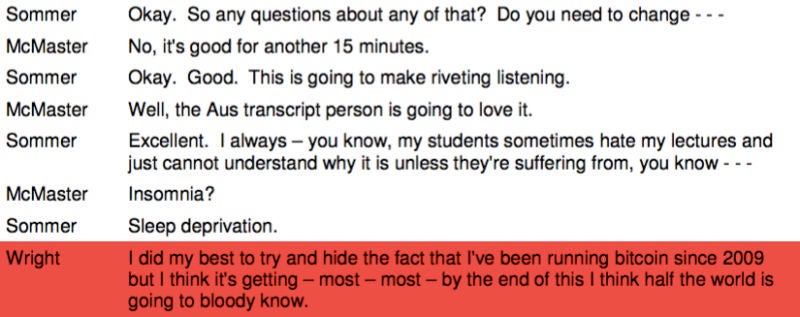

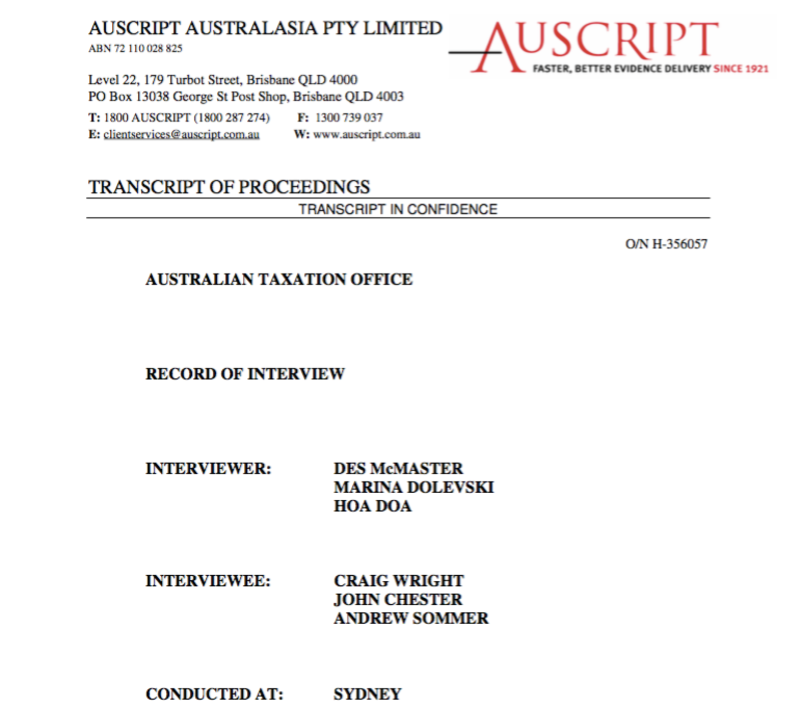

The hacker-tipster also included multiple PDF files that contain what appear to be a transcript of a meeting about Bitcoin regulation between Wright, his attorney, and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), as well as the minutes of a subsequent meeting of the ATO and Wright’s attorney. Wright appears to have been trying to persuade the Australian government to treat his Bitcoin holdings as currency, as opposed to an asset subject to greater taxation. Without this regulatory move, his business interests would be scuttled. During an interlude in one such meeting, Wright makes an oddly casual admission of his identity as Satoshi (highlighting added):

A request to confirm the authenticity of the document sent to Auscript, the transcription service whose logo appears at the top of the file, was denied on the basis of company policy. A request sent to the ATO was also denied on the basis of state confidentiality.

Multiple phone calls to Wright suggest that the material is, at the very least, not fabricated: In an initial call placed in November, he said he “couldn’t talk about” the documents we’d received, or the suggestion that he is Satoshi Nakomoto. On a subsequent call, in which lines from his purported emails were read back to him, an audibly unsettled Wright asked “how did you get that?” and stated “you shouldn’t have that.” He also confirmed that the people CCed in the first email were his attorney, accountant, and a coworker at one of his companies, DeMorgan Ltd. After those two calls, Wright stopped answering the phone, did not respond to emails, and made his Twitter account private.

Andrew Sommer, the attorney, refused to comment on the contents of the email or meeting transcripts, but did confirm that Wright was his client.

Contacted by phone, Wright’s ex-wife Lynn recalled her husband working on Bitcoin “many years ago,” but noted that he “didn’t call it Bitcoin” at first, but rather “digital money.” She also confirmed Wright’s friendship with Dave Kleiman: “I knew Dave...I knew they were friends and they talked about stuff, different things that were happening in the geek world...half the time he was taking I wouldn’t listen, hence the ex.” When asked specifically if Wright was the inventor of Bitcoin, Lynn replied “I’m not going to comment on things that we talked on.”

Ramona Watts is Craig Wright’s wife, a director at his company DeMorgan, and a recipient of Wright’s apparent email from Satoshi@vistomail.com. Reached by Gizmodo at their home in an moneyed suburb north of Sydney and asked about Wright’s role in creating Bitcoin, Watts at first only smiled, shook her head, and began to close the door. When asked if Wright was the inventor of Bitcoin, she smiled coyly again and shut the door.

John Chesher was Wright’s accountant, a recipient of his Satoshi email, and was present at one of the ATO meetings. When reached at his apartment via intercom and asked whether he’d ever received an email from Craig Wright using Satoshi Nakamoto’s email address, Chesher responded, “I might’ve...that was a year ago.” When asked if he had ever told the Australian Tax Office that Wright was in possession of a Satoshi-sized Bitcoin sum, he replied, “I may have.”

Ann Wrightson, a former employee of Wright’s who was also present at an ATO meeting, confirmed to Gizmodo that the meetings took place. She noted that she has cut all ties with Wright and Watts and is much happier for it: “Personally, he’s a nice fella, but, um, business-wise, I don’t believe he’s… He’s not a model to aspire to.” We asked Wrightson directly whether Wright had invented Bitcoin, and she demurred: “I’d prefer not to actually incriminate himself or incriminate myself...I’m sure if you’re a reporter, you can find other people to answer that for you.”

When a Gizmodo reporter visited the office of DeMorgan, Wright’s firm, Ramona Watts attempted to steer employees away from speaking to him, as seen above.

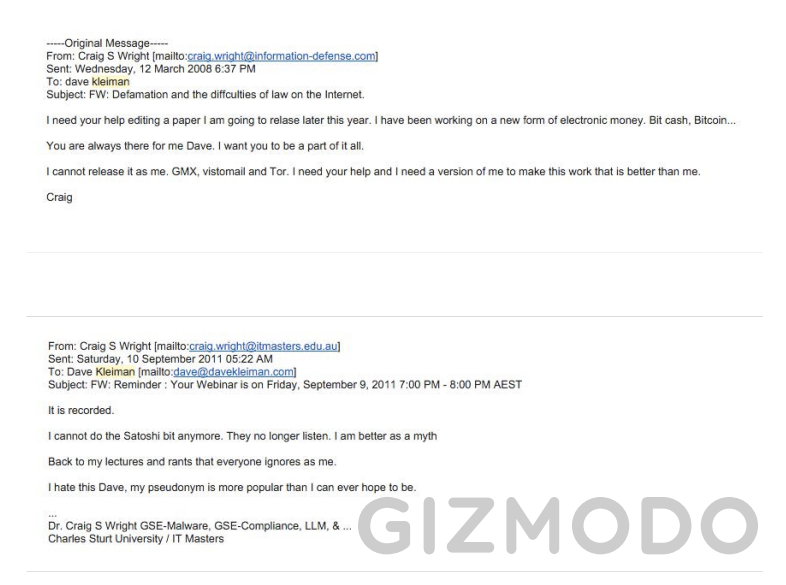

A purported email from March 28, 2008, months before Satoshi Nakomoto published the white paper that laid out the Bitcoin framework, appears to show Wright divulging the idea of a “new form of electronic money” to Kleiman for the first time. “I need your help and I need a version of me to make this work that is better than me,” the sender wrote, seemingly presaging the Satoshi persona.

Several years later, after Bitcoin’s value had exploded and the currency had permeated mainstream consciousness — and months before online accounts associated with Satoshi Nakomoto went dark — Wright wrote to Kleiman, with apparent fatigue, about the secrecy around his identity: “I cannot do the Satoshi bit anymore,” he wrote. “They no longer listen. I am better as a myth.”

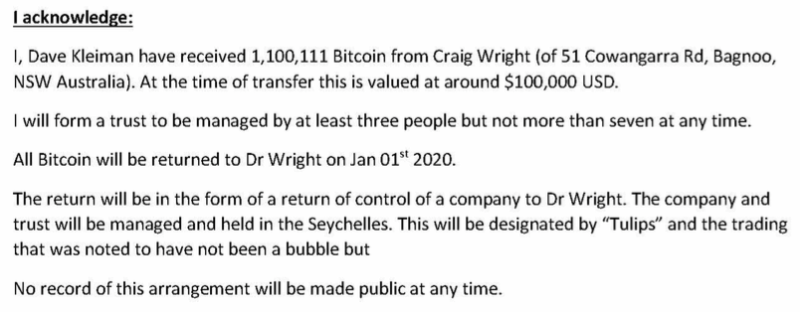

The hacker also provided a PDF file of what appears to be an unfinished draft of a legal contract between Wright and Kleiman forming a secret Bitcoin trust in the Seychelles, a notorious tax haven in the Indian Ocean. The contract shows Dave Kleiman in receipt of 1,100,111 bitcoin, to be repaid to Craig Wright on January 1, 2020. Several reports, including an oft-cited technical analysis by Bitcoin expert Sergio Demian Lerner, estimate Satoshi Nakamoto’s legendary Bitcoin fortune at around 1 million BTC — a figure that nearly matches the amount in the Seychelles trust. It also lists five PGP keys — files that are used to establish encrypted lines of communication over email — that will be used to manage the trust. Searching for those keys in a public database reveals that one belongs to Wright, one belongs to Kleiman, and two belong to Satoshi Nakamoto.

The contract also contains a clearly incomplete sentence fragment and several other strange details and inconsistencies. On June 9, the date on the document, one bitcoin was valued at roughly $31, meaning that the million-bitcoin cache would have been worth about $31 million U.S., but the document values the sum at just $100,000. The contract also claims that Wright is facing bankruptcy. According to Australian public records, Wright filed for personal insolvency in 2006 and was denied, but records make no reference to an insolvency petition in 2011.

The contract stipulates that if Kleiman should die, “Dr Wright will be returned shares in the Tulip trust and company 15 months after my death at his discretion.” Perhaps most bizarrely, it includes a similar stipulation for Wright’s death, bequeathing all holdings to Ramona Watts, his wife and colleague, minus a sum that would be used “to show the ‘lies and fraud perpetrated by Adam Westwood of the Australian Tax Office,” an Australian government employee whom he blamed for an unfortunate regulatory ruling against one of his Bitcoin-related companies.

In the contract, Kleiman also vows not to divulge “the origins of the satoshin@gmx.com email,” an email account used by Satoshi Nakamoto to publish the research paper announcing Bitcoin the world.

Patrick Paige and Carter Conrad, who run a Palm Beach County business called Computer Forensics, LLC, in which Kleiman was also a partner, formed their own suspicions about Satoshi’s identity after receiving a string of bizarre communications from Wright following Kleiman’s death in 2013.

Days after their friend and partner died, Paige and Conrad sent an email about his passing to a group of associates who may have only known Kleiman through a computer screen. He was rendered paralyzed from the chest down by a motorcycle crash while working for the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Department in 1995, and spent the final years of his life hospitalized with a deadly infection of the bacterium MRSA. Against his doctors’ recommendations, Kleiman left the hospital and returned to his home after nearly three years of treatment in 2013, Paige and Conrad said. The infection stopped his heart and killed him just weeks later.

Kleiman’s hospitalization only exacerbated what was already an isolated, sedentary lifestyle. “That motherfucker was on the computer nonstop,” said Paige, meaning that many of Kleiman’s relationships were strictly digital, and those friends wouldn’t be immediately aware of his death.

Among the recipients of that 2013 email was Craig Wright, a man whom Paige and Conrad understood to have a casual working relationship with their late friend. Wright and Kleiman had authored a paper together five years earlier on the mechanics of overwriting hard drive data, and they corresponded sometimes about other technological esoterica. So it was a surprise when, days after sending the email, they came across a mournful video about Kleiman on Wright’s YouTube channel. In the video, Wright narrates footage from Kleiman’s various TV appearances, growing increasingly emotional. By the end, Wright is audibly choking back tears. “I’m proud to say I knew Dave Kleiman,” he concludes. “I’ll miss you, Dave. You were my friend, and I’ll miss you.”

Paige didn’t know what to think of the video, but it wasn’t a total shock that Kleiman had maintained such an intense and largely secretive bond with a peer in a different hemisphere. Stranger, however, was a document that Paige and Conrad received in their business mailbox several months later, which bore an Australian return address and informed them that their late partner was no longer legally affiliated with a company called W&K Info Defense Research. The name was totally unfamiliar to both men, and, because the notice didn’t seem to require any action from them, they ignored it.

According to public records, W&K was founded in Palm Beach County in 2011, with Dave Kleiman as its registered agent and Kleiman’s home address as its place of business. In 2014, after Kleiman’s death, it was reinstated as an LLC with a new registered agent, a new place of business, and Coin-Exch, one of Wright’s companies, listed as an “authorized person.” A document purporting to show minutes of a meeting between Wright’s attorney and the ATO, which was provided to Gizmodo by Wright’s apparent hacker, also makes reference to W&K. In the minutes, Wright’s accountant John Chesher calls W&K “an entity created for the purpose of mining Bitcoins,” and states that Wright and Kleiman founded the company together.

The document also shows Chesher speaking about Wright’s spectacular Bitcoin fortune and indicating that Kleiman may have amassed a similar amount. It reads in part:

Craig Wright had mined a lot of Bitcoins. Craig then took the Bitcoins and put them into a Seychelles Trust. A bit of it was also put into Singapore. This was run out of an entity from the UK. Craig had gotten approximately 1.1 million Bitcoins. There was a point in time, when he had around 10% of all the Bitcoins out there. Mr Kleiman would have had a similar amount. However, Mr Kleiman passed away during that time.

According to Jeremy Gardner, a longtime Bitcoin investor and co-founder of the College Cryptocurrency Network, it is doubtful that anyone but Satoshi could’ve amassed Bitcoin holdings of that size: “I don’t think anyone comes that close, honestly.” However, Gardner also doubts that even Satoshi would still have that many coins:

The only person who could really have a million, and I imagine it’s much less than that, if any at all, is Satoshi. Anyone else who ever came close to owning that much, which I don’t believe ever happened, has long since liquidated a substantial portion of what they held (as the value of their holdings would have have gone up well over 250x).

The only thing zanier than Satoshi Nakamoto’s fabled Bitcoin vault would be the thought of another person possessing “a similar amount”—unless the stockpile was being held in some sort of secret monetary trust.

The next communication that Paige and Conrad received from Wright was stranger still. Emails provided to Gizmodo, the authenticity of which were confirmed by Paige and Conrad, show that in February 2014, 10 months after Kleiman’s death, Wright emailed the pair to tell them about a mysterious project he’d been working on with their friend. As part of this undertaking, Wright wrote, Kleiman had mined an enormous amount of bitcoins—an amount “too large to email.” Wright asked them to ensure that Kleiman’s computers were safe, and to check whether their hard drives contained wallet.dat files, the pieces of software that contain bitcoins and their owners’ account information. On a subsequent phone call with Wright, a baffled Paige asked for more information about the partnership with Kleiman. After that, he said, Wright assumed a clandestine tone. “Can I trust you?”

According to Paige, Wright eventually told him that Kleiman was the creator of Bitcoin. Later, he clarified that the cryptocurrency was invented by a group of people which included Kleiman. If that was true, Kleiman was likely sitting on a fortune when he died in April 2013—even if he were in possession of only half of Satoshi’s fabled million-bitcoin stockpile, that would have been worth about $65,000,000 at the time of his death. Wright made clear to Paige that he wasn’t after the money—he only wanted to make sure that it made its way into Kleiman’s estate and didn’t sit gathering dust in a digital vault.

Paige was stunned by the idea that his friend had achieved such an amazing feat, but when he considered it further, it didn’t fall apart entirely. Paige regularly refers to Kleiman as a genius in conversation, and his expertise in computer security aligns with the skill set that would have been needed to build—or at least contribute to—the bitcoin protocol.

Still, there were major questions. Another 2014 email provided to Gizmodo shows Paige telling Wright that Kleiman mentioned Bitcoin to him just once, and this month said he doesn’t recall the digital currency coming up any other time in his daily conversations with his partner. And according to those who knew him well, Kleiman needed money badly—his house was under foreclosure and he spent nearly three years in a VA hospital before he died. If Dave Kleiman were Satoshi Nakamoto—or one of several Satoshis—wouldn’t he have cashed out at some point?

Shyaam Sundhar, a computer security professional who coauthored an academic paper with Kleiman and Wright in 2008, doubted and expressed dismay at the idea that either man was involved in Bitcoin’s creation. “Our conversations has only been pertaining to HDD project,” he responded to an inquiry via email, referring to their research on hard drive data. “I would hope that what you have stated is mere rumors, since I have never heard any such thing about Craig or Dave.”

Paige and Conrad left the matter unresolved, and Wright stopped calling and emailing them after he made contact with Kleiman’s brother, the executor of Kleiman’s estate. “We knew one day a reporter would come calling,” Paige said. “But we left it at that.”

In November, after being contacted by Gizmodo, Paige emailed Wright to ask whether he planned to release any information about Kleiman’s—and by extension, his own—involvement in creating Bitcoin. “Not yet. We are in the process of finalising some of the research. I was hoping we could be at the point of release before the reporters started sniffing,” Wright responded. He added in a later email, “When it all comes out, there is no way Dave will be left out.”

While he was alive, Kleiman kept an aluminum-encased USB drive on his person at nearly all times. If there really is a cache of Kleiman’s bitcoins or anything else linking him to Satoshi, Paige said, “I guarantee that drive has some shit in it.” According to Paige, when Kleiman died, his brother, Ira Kleiman, took possession of it.

Ira Kleiman declined to speak on the record about whether he is in possession of his brother’s hard drives. Described by acquaintances as guarded and private, Ira Kleiman also refused to meet with a reporter in person or speak over the phone, opting instead to send dozens of cagey and cryptic emails and SMS messages in an exchange that lasted several days. He claimed that after his brother’s death, Wright contacted him and told him that he and Dave Kleiman were involved in creating Bitcoin, and also alleged to possess documents provided to him by several sources that might corroborate the information provided to Gizmodo by Wright’s apparent hacker. However, Kleiman declined to provide any concrete information about those documents or their sources, and would not answer when asked if he believed that Wright had been telling him the truth.

Additional reporting from Sydney by Daniel Strudwick

Top image by Jim Cooke. Contact the authors at andy@gawker.com and biddle@gawker.com.·

PGP fingerprint: 35B1 D6A7 BCED 9F9C C7D3 C9D7 65FA 8F8C 5B62 4809

Sam Biddle Public PGP key

PGP fingerprint: E93A 40D1 FA38 4B2B 1477 C855 3DEA F030 F340 E2C7