One of the most exclusive clubs in Great Britain is not full of hereditary peers and socialites, but instead counts former pilots and servicemen as its chief members. It’s called the Guinea Pig Club and membership dues are steep.

In order to join the Guinea Pig Club you had to have at least two reconstructive surgeries at Queen Victoria Cottage Hospital in East Grinstead, in the UK, by pioneering plastic surgeon Archibald McIndoe back in the 1940s. By the end of World War II there were 649 members, mostly from Great Britain, but also from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Czech Republic.

Before WWII, severe burns were rare and mostly due to household accidents. But the war changed that. Flying dangerous planes like the Spitfires and Hurricanes that were prone to accidents, full of highly flammable fuel that would spill over the pilots and crew, resulted in many otherwise healthy young men with disfiguring burns all over their bodies.

McIndoe, a native New Zealander, pioneered many of the treatment techniques still used today to treat severe burns. But he also recognized that to treat the trauma on the outside, you also have to treat the trauma on the inside. Thus the Guinea Pig Club was born.

Plastic surgery at the time was pretty crude. Even something as simple as how to best heal burns before reconstructive surgery could be attempted was a matter of trial and error. The prevailing wisdom at the time called for a special chemical coating usually applied to minor burns. It would form a protective layer to allow the burns to heal. But it proved disastrous for treating severe burns over large areas. The coating would dry out the skin, cause additional scarring, and was incredibly painful to remove. After trying the coating with little success, McIndoe observed that the burns of patients who had crashed into water would heal the fastest. So he started using saline baths for the burns instead to encourage healing.

When it came to reconstructing lips, noses and whole patches of skin on faces, more drastic measures were needed. A large sheet of skin taken from an unburned area like the thigh will not survive transplantation. McIndoe would carefully leave the skin flap attached at one end, roll it into a tube, stitch it up so there would be no infection, and attach it to another site closer to where he ultimately wanted it, like the arm. Once it had healed and started to draw its blood supply from the arm, he would detach it from the thigh and attach it from the arm to the face, where after it had healed, he could use it to reconstruct features. Patients had to walk around with their faces connected to their shoulders or arms by skin tubes that looked like little elephant trunks — but it worked. Large patches of skin survived and could be used to form new features.

Club member Bill Foxley endured 29 operations to rebuild his face. When his plane crashed he managed to make it out unharmed, but he ran back to the burning plane try to save the wireless operator who was still trapped inside. In his efforts to free him from the plane, Foxley was badly burned. (The wireless operator did not survive.)

One eye was destroyed, along with the skin, muscle and cartilage of his face up to his eyebrows; the cornea of the other eye was badly scarred. Foxley was never able to smile again because of the injuries. But that did not stop him from marrying one of his nurses at the hospital in 1947, or having a career after the war at the Central Electricity Generating Board. He developed a reputation for being hard on contractors when he would inspect their work by intensely studying it from a few inches away. The contractors never realized it was because he couldn’t see it otherwise.

Another patient, Sandy Saunders, was a glider pilot. When his plane crashed, he suffered burns on 40% of his body. His nose and eyelids had to be rebuilt. The experience inspired him to become a doctor. He would spend his recovery time between surgeries watching McIndoe operate on other patients, and dissecting frogs in preparation for his post-war career change.

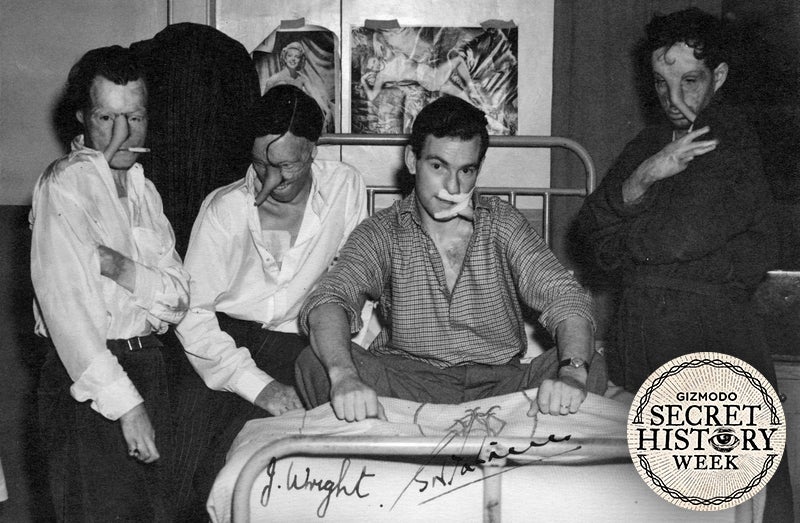

One of the most remarkable things about the Guinea Pig Club was the attitude of the doctors and nurses. They didn’t treat them like invalids in recovery. The staff took pains to create a cheerful and normal environment at the hospital, and McIndoe overlooked the often inappropriate flirtations of the lonely young men with the nurses. One nurse recalled how a patient with badly burned hands still managed to pinch her when she turned around. When she threatened to punch him in the nose if he ever tried it again, he pointed out that he didn’t actually have a nose. “I can wait,” she dryly replied.

The club members had a dark sense of humor. When the club was first formed, they selected a pilot whose fingers were badly burned as the secretary so that he couldn’t take minutes, and another pilot with badly burned legs as the treasurer so he couldn’t run away with club money.

They were all very young, mostly around twenty years old. Some were suicidal when they arrived at the hospital. They had survived when their friends had died. They thought their lives were going to be over.

So McIndoe brought in showgirls to visit them from London to convince them that they could still talk to pretty girls. He got them invited to tea at the homes of local families so they felt welcomed. He let them wear their uniforms in the hospital. He kept plenty of beer on the floors. After all, the Guinea Pigs were technically a drinking club.

It was one of the first efforts to focus on both the physical and the psychological recovery of patients. Before then, people with disfiguring injuries or disabilities were often hidden from sight. Instead of casting the burned pilots and crew as unfortunate young men with their lives cut short, McIndoe presented them as heroes to be lauded for their courage. If a play was opening or a movie premiering in town, McIndoe got his patients invited as guests of honor.

And it worked. Grinstead, where the hospital was based, became known as “the town that did not stare.” A number of the club members married women they met in the town while recuperating.

The motivation to reintegrate the members of the Guinea Pig Club into society was not entirely altruistic. The Royal Air Force had spent a lot of time and money training the pilots and was eager for anything that could return them to active duty. Still, it was a big change in attitude for the military, according to Emily Mayhew, historian and author of The Reconstruction of Warriors.

After the war, the former patients continued to meet for reunions. It was only in 2007, when the oldest member was 102 and the youngest 82 that they decided they were getting too old as a group to keep traveling to reunions. The Guinea Pig Club aptly demonstrates that the key to resilience is a little humor, social acceptance, and the knowledge that you are not alone.

Further Reading:

Andrew, D. R. (1994) “The Guinea Pig Club.” Aviation Space and Environmental Medicine 65 (5): 428.

Bishop, Edward. McIndoe’s Army: The Story of the Guinea Pig Club and its Indomitable mMembers (revised ed.). London: Grub Street, 2004.

Mayhew, Emily R. The Reconstruction of Warriors: Archibald McIndoe, the Royal Air Force and the Guinea Pig Club. London: Greenhill, 2004.

Images courtesy of The Guinea Pig Club, via East Grinstead Museum. Used with permission.