If you’re still lukewarm on the idea of parachuting in a bunch of beavers

That’s the conclusion of a study published this week in PLOS ONE, which adds a fascinating layer of nuance to the connection between fungi and rainstorms. Rain, as we know, stimulates mushroom growth, eventually leading to fully-fruited mushrooms that release spores. Once airborne, these spores, much like salt and dust particles, can act as cloud condensation nuclei — surfaces on which water vapor condenses, eventually forming rain.

“We can watch big water droplets grow as vapor condenses on [the mushroom spore’s] surface,” study co-author Nicholas Money of Miami University told Discovery News. “Nothing else works like this in nature.”

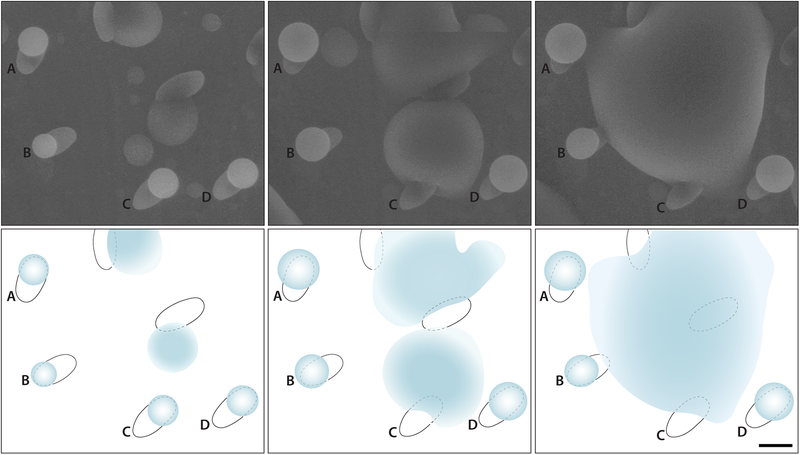

Rainwater condensing onto a the surface of basidiospores of Suillus brevipes. Top: Scanning electron microscopy. Bottom: Computer rendering. Image Credit: Hassett et al. 2015

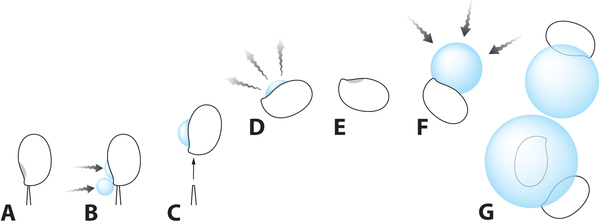

In their study, the researchers specifically looked at spores produced by Basidiomycetes fungi, a large phyla including thousands of mushroom-producing species. So-called basidiospores are released from the gill surface of mushrooms by a “catapult mechanism,” wherein the secretion of water-loving sugars causes a tiny ball of water to form around individual spores. This fluid motion results in a rapid displacement of the spore’s center of mass, imparting momentum and launching it skyward at up to 4 miles per hour.

Schematic of the mechanism of droplet formation on the surface of basidiospores. A-C: Condensation of water onto the spore surface leads to spore discharge. D,E: Water evaporates from the surface of the airborne spore. F-G: Condensation of water vapor onto the spore’s surface promotes raindrop formation. Image Credit: Hassett et al. 2015

In this manner, a single mushroom can release 30,000 spores every second; up to a billion a day. One study estimated that 50 million tonnes of spores are dispersed into the atmosphere each year.

And all of those tiny spores could be seeding clouds, influencing rain and climate patterns across the globe, according to the new study, which used scanning electron microscopy to watch the rain condensation process in action. “The kinetics of this process suggest that basidiospores are especially effective as nuclei for the formation of large water drops in clouds,” the researchers write. “Through this mechanism, mushroom spores may promote rainfall in ecosystems that support large populations of ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic basidiomycetes.”

Those ecosystems includes wet tropical rainforests like the Amazon, as well as the northern hemisphere boreal forests, where fungi chow through leaf litter and liberate essential nutrients during the short summer months.

Fungi are often lauded as nature’s ultimate survivors — terraforming the land before plants gained a foothold; inheriting and recycling the Earth after mass extinctions. But as we drilled deeper into their clandestine lives, it’s becoming clear that fungi don’t just adapt to their environment. The environment adapts to them.

[Read the full scientific paper at PLOS ONE h/t Discovery News]

Follow the author @themadstone

Top: Tom Sieprath / Flickr